We now have questions of the ‘desirability’ of queer marriages with opinions ranging from rejection of marriage, of monogamy, to advocating choice (of whether or not to marry). What is important, however, is that the questions are all out of the closet and subject of open debate in courts and outside.

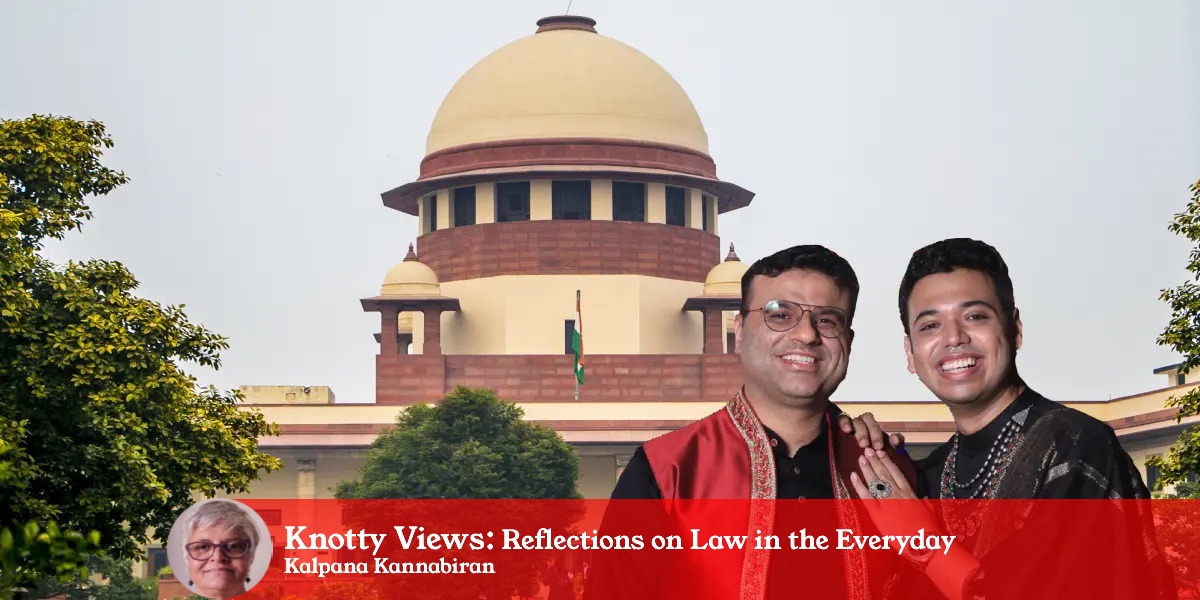

Supriyo Chakraborty and Abhay Dang from Hyderabad, who got married in December 2021, have sought recognition of same sex-marriages in the Supreme Court of India (Supplied)

On 6 January, 2023, the Supreme Court of India, considering petitions to amend the Special Marriage Act, 1952, to legalise same-sex marriages, transferred to itself similar petitions filed in various high courts in the country. It has listed the batch of petitions for directions on 13 March, 2023.

Around 2004, when our women’s collective, Asmita, began to work on transgender rights by bringing in discussions on non-binary conceptions of gender initiated by the late transgender activist Arun Chowdhary, we unearthed the little-known Andhra Pradesh (Telangana Areas) Eunuchs Act enacted by the Nizam’s government in 1919, and adopted by Andhra Pradesh in independent India.

This marked the beginning of Asmita Collective’s sustained engagement with gender not limited by heterosexual presumptions of binary gender or to women’s rights alone. My own work in this area began even earlier, in 2000, when I asked my students in law school to write seminar papers exploring gay rights, gay struggles, and prescriptive gender norms — forcing them and myself to step out of pedagogical and learning practices that are bound by heteropatriarchal gender ideologies. Needless to say, it was far from easy, but certainly illuminating.

So, when the Naz Foundation judgement decriminalising consensual adult sexual relations under Section 377 IPC came in 2009, it reinforced our work at many levels. The legal history of LGBTQI+ rights post-Naz is too well known to need further recounting.

The extent of stigmatisation of non-binary, non-cis, and cis homosexual communities is evident in the Delhi High Court’s application of Article 15(2) of the Constitution of India in Naz Foundation that prohibits discrimination in access to public spaces, and proscribes horizontal discrimination — between people inter se.

This provision was in the normal course understood as protections for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. Also relevant was the court’s reference to the Criminal Tribes Acts — a colonial legislation that criminalised nomadic and peripatetic communities, of which ‘eunuchs’ were one, according to Part II of the Criminal Tribes Act, 1871. This part was dropped in later amended versions of this Act, but by then the provisions had been written into the Eunuchs Act in Hyderabad state.

The binary, heterosexual entrapment of gender interlocks with criminalisation based on caste and ethnicity, migratory lifeworlds, and deeply entrenched prejudice against persons who live outside institutions of heterosexual monogamy.

While the UN CEDAW Committee (Concluding Comments 2014, para 11(i)) and Indian courts across the country have intervened in stellar ways to dismantle this carcerality with respect to gender, Parliament and the Central government today remain blindfolded by public morality, as is evident from arguments proferred in courts in response to petitions, and from the majoritarian stonewalling of legislative interventions.

There are three parts to this discussion in the domains of formal law: decriminalisation, equal protections, and familial rights.

Satrangi Mela, Hyderabad queer festival (Ajay Tomar/South First)

The past few years have seen three attempts at legislation on LGBTQI+ rights: A Private Member’s Bill that was piloted by Shashi Tharoor in Lok Sabha on 18 December 2015 (pp. 149 – 157) to amend Section 377, Indian Penal Code to legislatively decriminalise homosexuality, was defeated 24:71 without a debate.

A second Private Member’s Bill was introduced by Dr Senthilkumar in December 2021 seeking an independent enactment enshrining wide-ranging equal protections for LGBTQI persons.

A third Bill was introduced by Supriya Sule on 1 April 2022 (p. 1014) to amend the Special Marriage Act to include a provision for same-sex marriage.

Even while two suspended motions await parliamentary deliberation and decision, and one has been defeated, the Supreme Court in August 2022, in an intersectional, integrative move, set out the changing contexts in the understanding of ‘family’:

“26. The predominant understanding of the concept of a “family” both in the law and in society is that it consists of a single, unchanging unit with a mother and a father (who remain constant over time) and their children. This assumption ignores both, the many circumstances which may lead to a change in one’s familial structure, and the fact that many families do not conform to this expectation to begin with. Familial relationships may take the form of domestic, unmarried partnerships or queer relationships…These manifestations of love and of families may not be typical but they are as real as their traditional counterparts. Such atypical manifestations of the family unit are equally deserving not only of protection under law but also of the benefits available under social welfare legislation. The black letter of the law must not be relied upon to disadvantage families which are different from traditional ones.”

This observation, in a case of maternity benefits for a woman in heterosexual marriage, holds promise for destabilising the fixity of the gender-family nexus outside of heterosexuality.

Importantly, it interweaves enunciation of marital rights with rights in non-marital, queer relationships. There have been debates over whether marriage (an essentially patriarchal institution to begin with) and marital rights offer any resolution to discrimination against queer persons.

Participants at the Bengaluru Pride event on Sunday, 27, November, 2022 (Supplied)

These debates underscore the pitfalls of legal recognition of and institutional arrangements around intimate relations; and caution against the shifting of targets of discrimination to those who continue to live outside of marriage, irrespective of sexual identity/preference.

Should not inheritance, guardianship, parental benefits, workplace rights, all forms of employment, reproductive rights, for instance, flow equally to LGBTQI persons? Should such rights not be affirmed irrespective of relationship status?

This is a question that was also raised in the context of heterosexual marriage decades ago: Is marriage a necessary institution at all? Is it not built on fundamentally unequal and exclusionary principles?

Within marriage, should ‘arranged’ (endogamous) marriages exist at all? Or should marriage only be based on choice? Is it possible to advocate choice without rejecting marriage? Is a secular provision in the Special Marriage Act sufficient, or should there be a reframing of religious laws on marriage and family?

While the questions have been debated, they are far from resolved.

We now have questions of the ‘desirability’ of queer marriages with opinions ranging from rejection of marriage, of monogamy, to advocating choice (of whether or not to marry), to endorsing endogamous queer unions — how can we possibly escape caste, community, and class in India?

What is important, however, is that the questions are all out of the closet and subject of open debate in courts and outside, which include literary works like that of playwright Danish Sheikh. And we witness elected representatives in legislatures (with few notable exceptions) and their weaponised foot soldiers on the streets dipping deep into the morass of orthodoxy and obscurantism — public morality and vigilantism guiding their words and deeds.

Feminist writer Ruth Vanita’s book, Love’s Rite: Same Sex Marriages in Modern India (2005, revised 2021), is a precious work that helps us navigate the minefields of state, religion, law, desire, and politics in our attempts to better understand the workings of marriage as an institution in India.

Her account, in what might come as a surprise for the educated urban elite, speaks of young women in contemporary India — mostly from the working classes, spread out in terms of social location and religion — going through religious ceremonies to marry, often across caste and community, and female couples facing opposition entering suicide pacts and dying together.

These are not women influenced by feminist or LGBTQ struggles. Just ordinary women eking out their livelihoods (often meagre), and exercising their choice of same-sex unions in the normal course of their lives.

Just as there are families and communities that push some couples to suicide or separation, there are several instances she cites of families participating in religious rituals and recognising unions.

The state and ‘secular’ or ‘formal’ law don’t necessarily figure in these contexts. And custom is fluid and malleable, as we all know.

Vanita’s argument that “couples that go through the rites of marriage, with the benefit of some social recognition, are in fact married” (p. 302) and that “same-sex weddings performed with family approval and in some cases by priests, and acknowledged by the partner’s communities, are valid marriages, and function as such in society” (p. 303) is compelling. It forces us to look anew at histories of intimacies and relationships, their futures and the place of formal law in everyday lives.

Indeed, we might look at the ways in which interpretation of formal law (secular and religious) may be informed by customary practices ever in the making — drawing on the kinds of illustrations she provides.

Whether the institution of marriage is patriarchal is a different question altogether that must certainly guide feminist interrogation not just of LGBTQ marriage but of heterosexual marriage as well – indeed, not marriage alone but all the institutional sites of patriarchy in our society. That is a bigger political project on a different scale altogether.

The purpose in this commentary is to point to the fluidity of relationship rules as they are and have been shaped and lived, and to point to the signposts of fundamental freedoms necessary to craft intimate relationships in desired ways. To be as one desires to be and not to have to suffer state interference or moral policing (and policing on political correctness) on that account.

(This is the second article by Kalpana Kannabiran in this series titled ‘Knotty Views: Reflections on Law in the Everyday’. These are the personal views of the author)

(Kalpana Kannabiran is a sociologist and legal scholar based in Hyderabad. She is a recipient of the VKRV Rao Prize for Social Science Research (2003) and the Amartya Sen Award for Distinguished Social Scientists (2012), both awarded by the Indian Council for Social Science Research (ICSSR) in recognition of her work in the field of law.

She has published widely on interdisciplinary law and gender studies, and has most recently edited and translated The Speaking Constitution: A Sisyphean Life in Law (2022) by KG Kannabiran)

Jul 26, 2024

Jul 24, 2024

Jul 23, 2024

Jul 23, 2024

Jul 20, 2024

Jul 20, 2024