Growing green consciousness, court curbs on firecrackers, and state-imposed restrictions are crippling this once-thriving industry

A hoarding welcoming traders and customers to Sivakasi. (Vasudevan Sridharan)

Uma Maheshwari has contemplated killing herself several times in the recent past.

The 50-year-old widow is suffering from a crippling debt owing to her daughter’s wedding, her late husband’s prolonged illness, and son’s education expenses.

To top it all, her working days are dwindling, as are her wages, in step with falling sales for her employers.

“How can I even make kanji (porridge)? Even if I get the rice from the ration shop, how will I afford other ingredients?” she told South First resignedly.

Earlier, Maheshwari used to clock six days a week at a fireworks manufacturing unit in Tamil Nadu’s Sivakasi, India’s fireworks capital.

Her weekly wages could be anywhere between ₹1,500 and ₹2,000, depending on how many fireworks items she made and packed.

But her earnings have halved now.

Her tale symbolises the floundering lives of countless others in the arid town — and the fireworks industry itself.

Known as ‘Kutty Japan’ or ‘Little Japan’ for its industrious labour force, the town has proved an economic boon for locals and nearby villages for decades.

Interestingly, the arid town grew tobacco in the early parts of the previous century, until severe legal restrictions came into force. But the dry weather and low rainfall patterns in the region made it suitable to gradually switch to firework manufacturing in the middle of the 20th century.

In the past, problems like child labour, caste and gender oppression, shoddy labour practices, poor safety measures, illegal factories, and recurrent fire accidents have haunted the industry.

However, it faced the various challenges and issues and today, fireworks factories in and around Sivakasi — over 1,100 registered units and several thousand unlicensed set-ups — employ over 300,000 workers, while 500,000 more work in allied industries.

Across India, about 1.5 crore people are part of the fireworks supply chain in terms of transport, retail, and sales; in fact, their livelihoods depend on this industry.

The entire fireworks ecosystem is dependent on human workforce as no machinery is used, with labour payments accounting for more than half of the production cost.

For a long time, Sivakasi has been the hub of fireworks production in India, meeting as much as 90 percent of the country’s demand.

But as Maheshwari’s story indicates, all is not well with the sector.

The labour-intensive sector, has been on the decline in recent years.

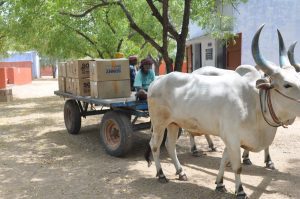

Boxes of packed crackers being transported from a manufacturing unit. (Vasudevan Sridharan/South First)

The industry was estimated to be worth ₹6,000 crore pre-pandemic but it should have been at least halved by now, say manufacturers.

And as this year’s Diwali sales unfold, it will determine where it is heading.

P Ganesan, president of the Tamil Nadu Fireworks and Amorces Manufacturers’ Association (Tanfama), the main collective of manufacturers, explained the issues weighing the industry down.

“First came all the troubles over child labour 20 years ago, then the heavy taxes in terms of excise duty, and then the curb on noise pollution. In 2015, the issues of air pollution dealt a blow,” said Ganesan.

“The pandemic is threatening to be the final nail in the fireworks industry’s coffin,” he told South First.

What is also not helping is a continuing ban on barium nitrate.

The Supreme Court has banned the use of barium nitrate — a vital but polluting ingredient — in manufacturing fireworks. Barium nitrate is so essential that it is used in almost 80 percent of all kinds of crackers produced.

Media reports say similar bans on various types of firecrackers has led to production dipping to as low as 10 percent in about a third of the factories; many face closure. Smaller units face shortage of raw materials without barium nitrates.

The pandemic aftermath and the heavy monsoons this year bode further trouble for manufacturers.

Over the past two decades, the industry has attempted to diversify its sales throughout the year by promoting aerial fireworks at political celebrations, weddings, and birthday gatherings.

This year, once again, much will depend on Diwali later in October for labourers like Maheshwari, who have been unsuccessfully betting on the festive season for more work and wages. Will Diwali bring some respite?

However, like previous years, multiple Indian states are expected to impose a complete clampdown on bursting crackers on Diwali, or at least severe restrictions are set to be in place.

While the demand for firecrackers among consumers prevails, restrictions such as the compulsory switch to green crackers (those that emit pollutants at a 30 percent lesser rate than their conventional counterparts), limited bursting hours, and anti-pollution campaigns have tightened the screws.

Also, unlike previous years, there have been no bulk pre-orders from bigger companies or bustling activities in the streets of Sivakasi. There have also been stockpiles from previous years.

Smaller manufacturing units at Sivakasi have said their production dropped by more than half.

Thangadurai, a supervisor with a major manufacturing company which he did not wish to be named, told South First that daily wagers at his facility has dropped from 400 before the pandemic to about a 100, and that too on a rotational basis.

“Between 80 and 100 boxes of crackers would be sent out every day,” he said of the good times. “It’s only 20 boxes at best nowadays.”

However, the ban on many categories of firecrackers over pollution issues could put a dampner on sales.

And this rankles Tanfama president Ganesan.

Arguing that the “fireworks and the industry are widely misunderstood”, Ganesan said pollution from fire crackers was minimal compared to the pollution from stubble burning in Delhi’s hinterland and increased vehicles on the city’s roads during Diwali.

“As Diwali coincides with all these, the effects of firecrackers look pronounced, which is not the case,” he argued.

“We are a soft and easy target for environmentalists,” said Ganesan.

The future looks gloomy for the industry, and that does not bode well for Maheshwari and her suicidal thoughts.

Dec 26, 2023

Aug 10, 2023

Apr 09, 2023

Feb 23, 2023

Oct 28, 2022

Sep 04, 2022