The Constitution stands on the side of the oppressed. I elaborate on this with reference to Champaran peasant testimonies gathered under Gandhi’s guidance.

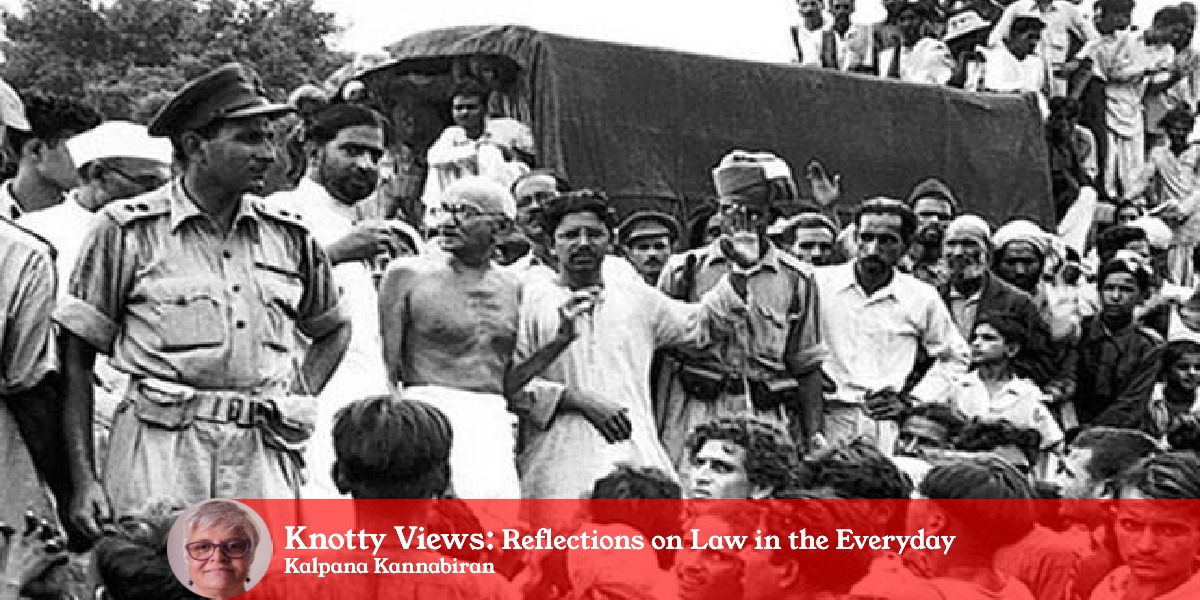

Can we forget that Gandhi’s Champaran satyagraha marks a stellar moment in the history of civil disobedience, that quintessentially Indian resistance to empire? (Twitter/IndiainJordan)

The Bharat Jodo Yatra concluded its first long march from Kerala to Kashmir, in Srinagar on 30 January 2023. The unprecedented communion of hearts, minds, hopes, and dreams across barriers has weakened the stridency of the ruling dispensation and enfeebled its speech and voice.

In considering the achievements on the ground, it cannot be forgotten that the Bharat Jodo Yatra was preceded and influenced by the anti-CAA protests across the country led by Muslim women, who as sociologist Ghazala Jamil points out, honed complex strategies of mobilisation to confront authoritarianism, by the protests against the abrogation of Article 370 in Kashmir, and by the farmers’ protests — all in a span of three years from 2019 to 2022.

Rahul Gandhi’s Bharat Jodo Yatra has been attracting both the committed and the curious (South First)

This included, importantly, the public performance of the Constitution of India as a commons that belonged equally to all. Outside of the arena of electoral politics, disregardful of majoritarian acrobatics in Parliament, people spoke and walked for a free India once again.

We are still hundreds, perhaps thousands of miles away, from reinstalling a democratic, plural, and representative government, but the initial strides, it seems, have taken shape and direction — the public response to Pathaan and the fearless screening of the BBC documentary on Gujarat 2002 are but two illustrations of the emerging collective resolve to thwart curbs on celebratory public participation, majoritarianism, and state impunity. Enough, no more. Let’s also say ‘Never Again.’

All of this is about our lives in law.

Being in and with Jammu, Ladakh, and Kashmir is about being willing to open up a new conversation on Azaadi and the Constitution. Difficult, but necessary and possible.

Pathaan’s travails were about repressive law, its soaring victory is about tilting the scales ever so slightly, imperceptibly almost, against authoritarian diktat — free expression, solidarity, and collective determination to free cinema from the mob.

Every bit of Gujarat 2002 is about the undermining of the Constitution and about the two-decadal struggles to reinstate the Constitution in letter and spirit.

And so, we are at the present moment, immersed body, soul, and heart in the life-giving waters of the Constitution.

Police detaining the students who planned to screen the BBC documentary in Osmania University (Screengrab)

I wrote this piece on 30 January, and my thoughts are with Gandhiji. What are the lessons that call for our attention?

The Constitution of India in my understanding stands on the side of the oppressed, exploited, and excluded, and strengthened their claims of equality, liberty and justice. Its genealogy lies in the anti-colonial and anti-caste struggles on the Indian subcontinent leading up to Independence.

I elaborate on this here with reference to the Champaran peasant testimonies gathered under Gandhi’s guidance. My account draws on a remarkable text that has just been published jointly by Navjivan Trust and National Archives of India: Thumb Printed: Champaran Indigo Peasants Speak to Gandhi (2022) — edited and introduced by Shahid Amin, Tridip Suhrud, and Megha Todi (hereafter TP).

One of the many insurgent efforts at confronting a criminal regime with the evidence of its depredations — in this case the colonial government — this work helps us make sense of the moment we are living through today and underscores the inestimable value of public participation in truth-telling for radical transformation. For, can we forget that Gandhi’s Champaran satyagraha marks a stellar moment in the history of civil disobedience, that quintessentially Indian resistance to empire?

The year is 1917.

“To us there is no Government, but that of the planter. He claims that everything belongs to him and he has the right to take it” – Babu Nandan, 30 April 1917, TP, p. vii.

For the present, the method undergirding that moment of disobedience is instructive, especially in terms of our ongoing and future engagements with live law.

Following his ‘voice of conscience’, Gandhi responded to a plea to help indigo raiyats secure justice in the face of unfair treatment by indigo planters (TP, p. lvii). He instructed a group of lawyers including Rajendra Prasad to visit several villages and record testimonies of indigo raiyats — 4,000 raiyats were examined, their statements recorded “after careful cross-examination…and many judgments of courts studied”. (TP lix).

In the 378 testimonies presented in this volume in the form of sworn affidavits with signatures and thumbprints of testifier and recorder, the specificities of dispossession, coercion, and overt violence are recorded in great detail; as also the details of land, rents, working conditions in indigo factories, and the ways in which indigo disrupted local agricultural cycles in each case, with the dating of events — “under a carefully designed protocol of public evidence gathering, often in front of local officials”. (TP, Foreword, p. xiv).

As historian Shahid Amin observes in his introduction to the volume, the focus on the indigo factories “offers us a peasant archive of tremendous power and richness. For, when the peasant speaks, the whole world speaks”. (TP, xxxvi).

On the peasants’ refusal to comply with demands for increased rent, or livestock or labour in the factories, criminal cases, illegal detentions, physical violence and coercion were commonly used.

“After I have been released on bail in the criminal case which is still pending… the factory peon with the help of additional police took me to the factory where I was assaulted for not paying rent.” (TP, Gopal Lal, village Jasauli, p. 7).

“I cut a branch of my own tree for which I was detained for three days in the kothi by the police at the instance of the factory.” (TP, Hiran Tiwari, village Banbirwa, p. 9).

“They beat me and my brother with fists and kicks. I was compelled by force to put my thumb mark on a piece of paper in the indigo godown. I don’t know what that document is.” (TP, Mahadeo Rai, village Jasauli, p. 18).

“My house was…looted in Chait last by the kothi. The jiladar and sipahis went and looted my house. I was not at home at the time.” (TP, Phadi Mian, village Banbirwa, p. 51).

In speaking of their particular predicament, the peasants were in fact decoding colonial rule and identifying the touch-points for intervention.

While it is not possible to provide a detailed account of the political import, legal process, and impact of the testimonies of the indigo peasants here, the book provides a rich account of the method and history of the politics of organising civil disobedience and popular resistance.

The focus, as editors Tridip Suhrud and Megha Todi observe pertinently in their introduction, is on the collective will of the peasants of Champaran who came forward to testify and speak the truth of their condition despite grave threats to life and security — with Gandhi crafting the method for the recording of the evidence (TP, p. xxxvii). It must be remembered that this evidence, although not presented before a court of law, was nevertheless an enduring archive of resistance and nonviolent disobedience.

As we return today to a historical moment that is saturated with widespread disquiet over arbitrary governance and the derailment of justice and fairness in the everyday transactions of the state and dominant actors, notably corporations, the intellectual history of disobedience in the face of dispossession, oppression, and disentitlement bears remembering.

The thousands of thousands of ordinary Indians who marched with, witnessed, and met the Bharat Jodo Yatra at various points are people with a keen sense of what ails our society today and nurture a hope of recovery and healing.

To translate this into the language of satyagraha — Gandhiji’s and Babasaheb Ambedkar’s, straddling Champaran and Mahad — is where the challenge of inscribing constitutional memory lies. And from there we may build the pathways and bridges to recovering a democratic polity and society.

(This is the third article by Kalpana Kannabiran in this series titled ‘Knotty Views: Reflections on Law in the Everyday’. These are the personal views of the author)

(Kalpana Kannabiran is a sociologist and legal scholar based in Hyderabad. She is a recipient of the VKRV Rao Prize for Social Science Research (2003) and the Amartya Sen Award for Distinguished Social Scientists (2012), both awarded by the Indian Council for Social Science Research (ICSSR) in recognition of her work in the field of law.

She has published widely on interdisciplinary law and gender studies, and has most recently edited and translated The Speaking Constitution: A Sisyphean Life in Law (2022) by KG Kannabiran)

Feb 10, 2024

Sep 17, 2023

Sep 11, 2023

Apr 25, 2023

Feb 01, 2023

Feb 01, 2023