In his autobiography, M Kunhaman relates chilling experiences that expose progressive Kerala's hidden anti-Dalit face.

Eminent economist M Kunhaman at a seminar. Photo: Special Arrangment

Eminent economist and powerful Dalit voice M Kunhaman is an exception in India’s most literate state, where authors and the intelligentsia are often subjected to public sarcasm for their eagerness to acquire power, positions, and recognitions.

This distinguished professor, who recently winded up his academic activities and settled on the outskirts of Thiruvananthapuram, proved this once again when he decided last week not to accept the Kerala Sahitya Akademi’s award for the best autobiography in Malayalam.

The autobiography Ethiru was a publishing sensation in Kerala.

“The book is not a glorification of my achievements in life. I visualised it as a window into the Dalit situation in Kerala over the years,” Kunhaman told South First. Although, he does plan to soon bring out an English version of it.

Asked why he refused the award, Kunhaman said he had never written anything for awards. “I am opposed even to the mere concept of awards,” said the retired professor.

The book contains several chilling instances in which he fought the caste hierarchy with sheer will and determination.

The autobiography of Kunhaman in Malayalam. (Supplied)

When Kunhaman bagged the first rank in MA Economics from Calicut University in 1974, he became the first Dalit after diplomat-turned-statesman KR Narayanan — the 10th President of India — to make achieve the seemingly impossible in the so-called progressive state of Kerala.

After winning the rank, he spent about two years searching for a job, according to the book.

Then pursued a PhD at the Centre for Development Studies (CDS) in Thiruvananthapuram, where renowned economist KN Raj was his guide.

On one occasion, he told his guide that if Raj had had an upbringing similar to that of a poor landless Dalit like him, there would be little or no chance of him passing the school final examination.

Kunhaman added that he might have won the Nobel Prize if he had the childhood Raj had had.

Today, Kunhaman is recognised as an eminent economist whose in-depth studies on land distribution and agrarian relations in the country could be unmatched.

He also taught for several years at the Economics Department of Kerala University and the Tuljapur campus of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS).

Ethir, roughly translated as “opposite” or “adversity”, is in fact his semi-autobiographical recollections.

The autobiography, marketed by Kottayam-based DC Books, portrays the Dalit existence and survival struggles in Kerala, a state that boasts of its renaissance legacy and progressive socio-political situation.

Born in the Vadanamkurissi village in Palakkad district to landless Dalit agrarian workers Corona and Ayyan, Kunhaman terms his life so far as a constant battle against poverty, fear and inferiority complex.

According to him, his cowardice and lack of confidence have been constant companions.

A former member of the University Grants Commission (UGC), Kunhaman was once considered by Kerala’s ruling Left Democratic Front (LDF) as a suitable person to become the vice-chancellor of Kerala University.

On several occasions, he was also considered for the position of a member of the Kerala State Planning Board.

But he believes people from the upper strata of society with great manipulating skills have took those positions away from him.

Finally, he had to move out of Kerala to join TISS, where he found discrimination was less prevalent.

Kunhaman belonged to the Panan community, the lowest among Dalits in Kerala.

In his childhood, he had to satiate his hunger with leftover food from local households.

There was only one kerosene lamp in his thatched hut, and his studies at night were disrupted when his mother took the lamp to the kitchen to make rice gruel.

“After I achieved the first rank in MA, there was a felicitation ceremony in Palakkad where two senior Kerala ministers were chief guests. I borrowed money from a neighbour for the bus tickets to reach there. A gold medal was presented to me on occasion. But within three days, I sold it to buy food and grocery for the family,” he recalled in the book.

His attempt to become a lecturer at Kerala University under the open merit quota failed, although he had emerged on top among the 32 applicants.

“Kerala is always boasting of an egalitarian society with strong notions of social justice. But no Dalit will sit on the chair of the chief minister in the state. If a Dalit wants it, they will have to be reborn as a bug,” opined Kunjaman in his book, which discusses Marxism, the caste situation in India, the renaissance legacy of Kerala, liberalism, capitalism, Naxalism, and the eminent Marxist theoretician and former Kerala chief minister EMS Namboodiripad at length.

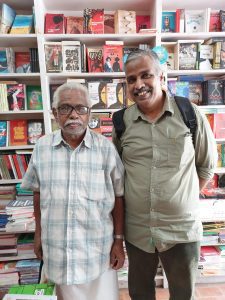

Kunhaman with journalist K Kannan, who co-authored Ethir. (South First)

Kunhaman started his fight against caste-based discrimination while studying the third standard. When his class teacher commented that Dalit children were attending school only with the motive of getting a free noon meal, he objected strongly and started skipping noon meals. He had to starve every noon for the rest of his school years.

On one occasion, he went to the house of the local landlord to get some rice gruel. As per the prevailing practice, a pit was made in a corner of the courtyard, and the rice gruel was poured into a plantain leaf there. When Kunhaman started eating it, the upper-caste landlord released his hungry pet dog to share the gruel with Kunhaman from the same pit. In the book, Kunhaman describes it as a competition between two hungry dogs.

Though he is critical of Communists in Kerala, Kunhaman reveals he greatly respects EMS.

“Despite his Brahmanic background, EMS showed the rare quality of considering all Dalits his equals. During my childhood, he came to our huts and sat comfortably on the floor smeared with cow dung paste. On numerous occasions, I attended meetings chaired by EMS and used them to criticise him and his perspective on Marxist philosophy. On all such occasions, EMS showed intolerance towards me. He once told me that he liked criticism and was not a God who feared criticism,” recollected Kunhaman.

Another former Kerala chief minister, VS Achuthanandan, and former finance minister TM Thomas Issac on many occasions assured him of positions in the state hierarchy to utilise his expertise for the betterment of the poor and the oppressed in the state.

“But nothing happened,” he recalled. “A Dalit vice-chancellor might have limitations in changing the higher-education system in a way that upholds the values of social justice. But we require large-scale Dalit participation and involvement in all areas of administration and governance,” he said.

For Dalit empowerment, Kunhaman recommends more Dalit control over wealth and various resources. “Dalits across the country need to learn how to make more money and use it wisely. In my opinion, economic liberalisation has benefitted at least a segment of the Dalit population in the country. In recent years, new capitalist Dalits have emerged across India. The recent floating of the Dalit Chamber of Commerce indicates such liberation,” he said.

Kunhaman also believes that the country needs more Dalits with radical intelligence and good scholastic capabilities. “Finding common grounds between Marx and Ambedkar is a waste of time. They are poles apart,” said Kunjaman.

He also believes that Kerala’s much-trumpeted land reforms failed to benefit the state’s Dalits and tribals.

“At the practical level, the land reforms created a new set of oppressors in the state. The working class did not benefit from it. The country needs more democratic discourses, and only they can help empower the weak,” he said.

Apr 26, 2024

Apr 26, 2024

Apr 26, 2024

Apr 26, 2024

Apr 26, 2024

Apr 26, 2024