Published Sep 03, 2023 | 12:00 PM ⚊ Updated Sep 03, 2023 | 12:30 PM

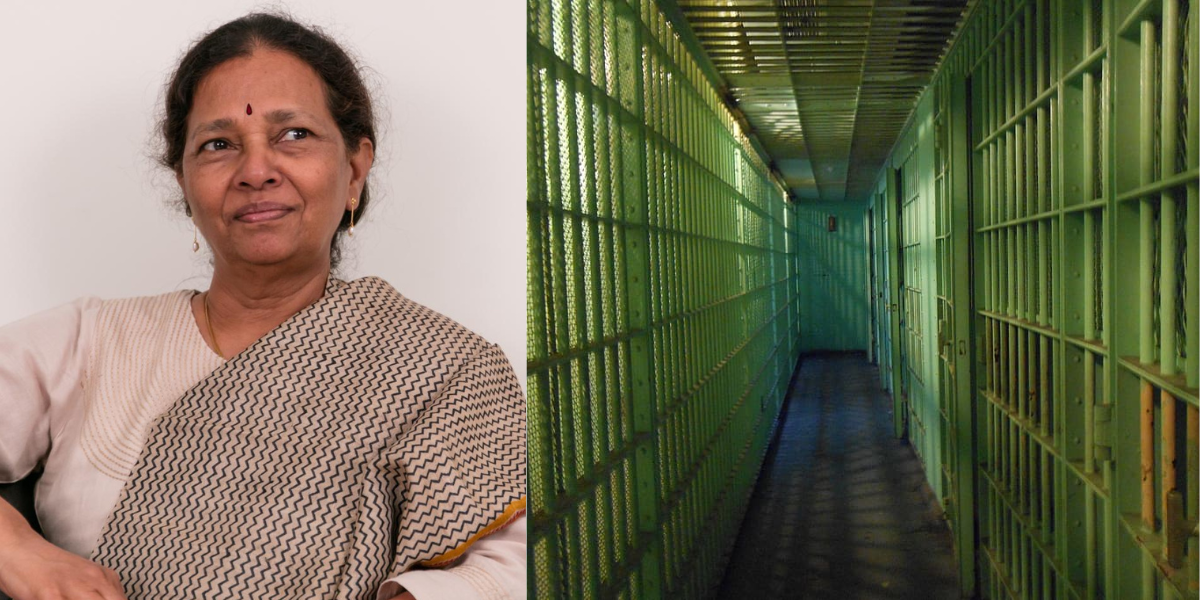

Of the 15,000 inmates who have been a part of the Unnati prorgramme, only about 200 have return to prison for another crime. (Supplied/Creative Commons)

Not just one or two but thousands of inmates who have committed serious crimes have opted to change their lives through Unnati — a cognitive behavioural change programme — to give themselves a second chance.

South First brings to you the story of two of the ex-prisoners — Veda Vyass aka Chinna Bhai and Balingam whose life changed, thanks to Unnati.

My family was rich. I was influenced by one of my grandfathers, who was known as “Don” in Dhoolpet, Hyderabad, and my other grandfather was in the Crime Investigation Department (CID). My father was a politician in the 1980s. I have three siblings one brother and two sisters.

I carried with me my grandfather’s and father’s pride — one a don and the other a politician — so I would walk the streets with groups of people and participate in rowdy fights. I became addicted to cigarettes at age 15. I studied till class 10 but during my intermediate, I rarely went to college. And even if I did go, it was to protest with gangs (groups).

I followed in the footsteps of my grandfather, who was involved in murder and land disputes, and ironically, he was murdered one day. I continuously failed to clear my Intermediate exams, though I was bright in academics, so one day, I used my father’s influence and passed Economics.

I was part of the Hindu Vahini Organisation to protect Hindu girls from Muslims. We would use weapons to harm Muslim men who were seen with Hindu girls. One day, in 2004, we were arrested by the police. We were in remand for 21 days in Chanchalguda jail and it was a celebration when we got out.

In the time I spent in prison, I learnt a lot of things and being addicted to Ganja was the newest on my list. This pushed me into thinking about getting into the drug business. Nobody on the streets knew my name was Veda Vyass. Due to my family background, I wanted to be named differently so I changed it to Chinna Bhai.

With these communal hatred cases, I was frequently arrested by the police. I was threatening people at night with knives and robbing them, drinking alcohol with that money, and hitting police officials. I became a rowdy sheeter.

I kept bad company with groups I met in jail. They would encourage me to do nothing but crime, eat, and sleep. Because of this, there was damage done to my family name. They were frightened to come and talk to me as I was an arrogant drunkard.

As time passed, I trapped a woman, pursuing MBBS, who was from a rich family. I lied to her that I was an MBA graduate and got married in a temple under the influence of alcohol in 2008. But later, she came to know all about me when I was picked up by the police. My sister’s husband also left her, my brother lost his journalism job, and my father lost in the elections.

We lost everything as I moved from Chanchalguda to Cherlapally to Karimnagar, and even Mumbai police stations. A task force also planned an encounter on me in the wrong case. I was surrounded by 300 notorious criminals and planned to kill myself in 2016.

We were made to sit in a room and the first thought that came to us was, “What is the police sketch today?” But we saw a woman walk in asking, “How are you? Have you eaten something?”

At first, we were all wondering what this woman could do, but it is at Unnati that we changed. Our future was put in front of us.

In prison, usually, there is nobody to ask us to do something. But we started coming back to the programme and I was counselled. All my family members were requested to give me one last chance to change in life.

After all these classes, with ₹11 lakh, I settled my cases because I did not want to come back again. Then, Beena Ma’am helped me get a degree and learn English, and I got a job at ValueLabs. But when we join a job, our history is checked and often spoken about in the office. So, I decided to get into the food business and also work at Unnati as a volunteer. I established a restaurant and worked in Dilsukhnagar.

Who would ever ask a criminal if they want to live a happy life? Beena Ma’am did and I take her name whenever people ask me how I changed my life.

I have studied till Class 9 in Kapra of Kushaiguda, Hyderabad. My parents were daily-wage labourers and I grew up watching my friends buying eatables and looking good, but I had no money.

So along with a group of friends, I started breaking into locked houses during the first half of the day because at night, it would be conspicuous. After the third robbery, I was picked up from my house by police and sent to a juvenile home in 2006 and nobody at home even knew.

Later, when one of the NGOs visited us, they informed my parents. They came with bail and I was released, but I learnt nothing from that incident and kept on committing crimes.

I never knew how to sell gold so I used to keep what I stole at home and the police would recover it. My parents would beg me not to commit crime but I continued indulging in thefts for years. My last jail time was in Warangal, I was in lock-up for 16 months.

Here, Beena Ma’am showed me a mirrored version of myself. She explained that while I committed the crime with friends, they weren’t in jail. This this led to change. I attended her counselling sessions and deleted crime from my mind.

Now, I am married and I have settled down. I am a proud individual. I dreamt of walking in front of the police station with pride and I’m doing it.

Talking about the origin of Unnati, Dr Beena Chintalapuri, Head of the Unnati programme, told South First, “VK Singh, former director general of prisons in Telangana approached me after listening to one of my speeches at the Correctional Services Academy. I was trying to understand if anything could be done for the inmates as the barracks in prisons were full of people. They also wanted to reduce recidivism and that’s how Unnati started.”

“I thought I would structure the programme using cognitive psychology models because until we change their mindset, it becomes difficult for them to stop their negative activities. With that intention, I planned a programme and introduced it first in Cherlapally Central Jail. Later, I took it to various other district prisons,” said Beena.

She added, “I thought I would be there for three or four months and just introduce the programme, because I had plans to go abroad.

So, once the programme was initiated, Beena kept track of the participants who came to the programme for about three weeks. Some of them were released and while many of them would have typically returned, those who attended the Unnati classes didn’t.

“When we contacted these released prisons over the phone, we came to know that they were all doing well and doing farming, etc. This was a very inspiring and motivating start for me because I realised that through this programme, we were making a difference in the lives of these inmates,” said Beena.

Initially, Beena had no one on her team. Later, a few psychology scholars visited the prisons along with her, but Beena realised that it was difficult for them to give up their work and come and go on with this work on a long-term basis.

“So, I requested the prison authorities to give me a long-term prisoner who can advise and share experiences that I could use as examples because I came from a university context,” said Beena.

She continued, “As I trained these long-term prisoners from other prisons, who were transferred, they learnt and started making a change in other inmates’ lives. There were 40 facilitators from across the 10 prisons who made Unnati a vibrant programme.”

The prisons helped the team with a separate hall, chairs, tables, and sometimes chai and biscuits. Beena hopes that if the Telangana government can help them with facilities and finance, they can continue the Unnati programme.

As if it were written in the stars, the Unnati programme caught the eye of ISRO. As Beena knew the officials from when she was teaching at Osmania University, they came forward with an application to submit under their Corporate Social Responsibility wing. “We finalised the proposal and we signed an MoU with Antrix and Prisons of Telangana state. This allowed me to hire two research assistants,” said Beena.

V Raghu Venkataraman, former executive director of Antrix Corporation, told South First, “It is the most cost-effective training programme, which has benefitted a large number of inmates to live a meaningful life. It has given them tangible benefits compared to other training programmes. The grant was given twice — once in 2017 and again in 2020, There is a subcommittee board for Antrix’s CSR activity and the report submitted by Unnati was examined by it.”

He added, “I have been supporting Unnati for a long time and now that I am retired, I help them administratively to ensure they are doing their scheduling right and proposals are drafted correctly for government entities. So my work is project management.”

“My two team members are now seriously working on sending proposals to other states. One proposal clicked with the Bureau of Police Research and Development, a Delhi-based organisation that encouraged us to come up with the same model for Tihar jail of Delhi. We have signed an MoU with Osmania University and Bureau of Police Research, and are now waiting for the grant to arrive to kickstart Unnati in Delhi,” informed Beena.

“Though my presence is very sparse now, I am told that some prisoners inside continue to make changes in their inmates and this motivates me to work harder. I have seen many cases — from a poor person to a businessman earning crores — and I have got the same respect from each of them,” she added.

Sometimes, Beena also speaks with the prisoners’ families. Most tell them that the reformed prisoners are now very happy with the change and they have been mainstreamed well, gotten married, taking care of their family, and completely off drugs.

“I have one released prisoner who was very popular. He told us that since his release, he has stopped at least 100 others who were on the brink of committing crimes,” shared a beaming Beena.

“I get calls from sincere inmates who contact Unnati when they do something wrong. One of them contacted me at 11:30 pm recently, saying that he was very sorry for having consumed alcohol. I am happy they share everything honestly,” she added.

“Our records show that we have helped at least 15,000 inmates through Unnati and only very few — around 200 — came back after another crime. To me, that’s not enough, we should be able to do more. That’s the reason I agreed to move on to other prisons,” said Beena.

She added, “Wherever we go, we work on making the programme self-sustaining and we train and develop personnel. Some of them require counselling and we complete that in Unnati class. This is a serious training programme with individual cognitive-based activities. From each activity, we draw behaviour and show them that this is where they stand. We explain to them that if they are setting their goal realistically by giving up on their offensive behaviours, then they will be successful.”

Beena has worked with Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (NDPS) prisons. She stated that the personality of inmates there is different and that they had to tweak their structure accordingly.

“The ones who were deep into drugs realised that they regretted it. So telling them that it damages their health is unnecessary because they know it already. We instead make them question why they need to use and get them to audit their own substance and alcohol use. After that, we ask them if it was worth it,” added Beena.

The youngest psychology research assistant at Unnati, Sandhya, told South First, “The experiences I had inside the prison are inspiring because each one of them is going through something negative. In one of the activities, we had to shift the inmates’ focus to look at the positive side of themselves. By the end of that, I, myself, was able to understand that inmates can also change their lives.”

Here’s an instance that stood out the most for Sandhya. “As we were low of resources, we had to work with limited material; we could not provide the prisoners with any material at times. So, the inmates themselves wrote what we did in class in their own handwriting and made a mini manual of what activities happen at Unnati. This they later passed on to new inmates. This is the dedication outsiders should learn,” she said.

With the belief that no one is beyond saving, Beena and her team at Unnati hope to change more lives within the prison systems of India.