Hyderabad city Commissioner of Police CV Anand in Telangana High Court said that FRS is entirely legal, under various provisions of law.

The police department is empowered to conduct regular checking for preventing suspicious activities in society to maintain law and order, said the official.(Supplied)

It was the second wave of Covid-19 in Hyderabad. The government had imposed a partial lockdown, allowing citizens to finish their work between 6 am and 10 am.

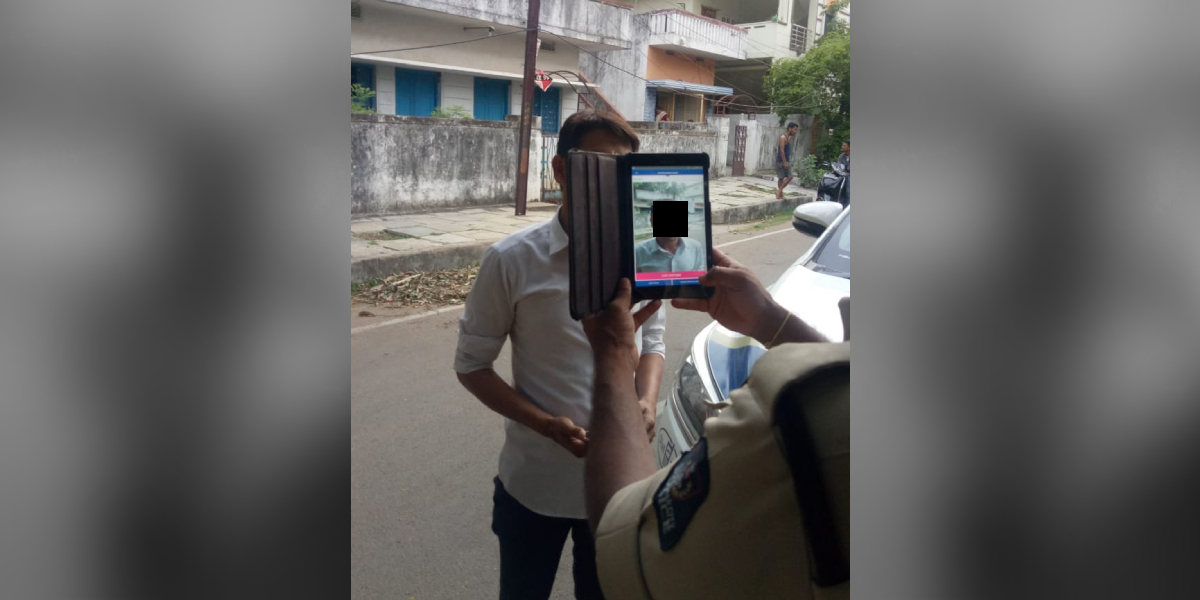

SQ Masood, a city-based social activist, went to Chhata Bazar for some work. On his way back, two police personnel stopped him around Shahran Market and asked him to remove his face mask.

“I asked them why they were telling me to remove my mask when they were penalising others for not wearing one,” Masood told South First.

The cops, though, had their way: They clicked his photograph on a tablet PC. “I was not the only one. These police officers took photos of several others,” said Masood.

He added that he was worried about where his photograph would be used or what the police personnel would do with it.

“They have access to various databases, such as those for prisoners, history-sheeters, habitual offenders, terrorists, Maoist, and all kinds of persons involved in crimes. It frightened me to think where they could put my photograph, who they shared it with, what they would use it for,” said Masood.

After consulting a few friends and colleagues, he sent a legal notice to the police and sought information on the law under which his photo was taken, if it was stored somewhere, and for how many days, besides details on who would be able to access it.

“They did not reply to my notice,” said Masood.

Eventually, after many months, he approached the Telangana High Court over the matter, asking whether there was any law on facial recognition. The case is pending in court.

Meanwhile, in an affidavit, the Hyderabad City Commissioner of Police CV Anand told the Telangana High Court that facial recognition systems (FRS) were entirely legal under various provisions of law.

The police department was empowered to conduct regular checking for preventing suspicious activities in society to maintain law and order, he said.

FRS is a standalone tool to aid investigation officers in the prevention of crime. It involves the identification of criminals or suspects.

It compares the face of a person moving under suspicious circumstances — or suspected of committing an offence — with a database of arrested offenders, convicted criminals, wanted persons, missing persons, and even children.

The data is stored in the central database of the CCTNS, maintained by the Central government.

“In no way is the FRS deployed covertly and non-consensually, as alleged by the petitioner [Masood],” the police said.

However, Anand said during the Annual Press Meet of the Hyderabad Commissionerate on 21 December that the police in Hyderabad do not use FRS. “We don’t use FRS as it amounts to human rights violation,” he said.

Facial recognition technology works by scanning spatial points on a person’s face. (Creative Commons)

FRT works by scanning spatial points on a person’s face.

“Think of how face-unlock works on phones. It maps dozens of points on your face and the distances between them, and uses that to create a unique map of everyone’s face,” said Sidharth Sreekumar an advocate of ethical technological advancement and Senior Product Manager at the Economist Intelligence Unit.

“Once this is done, FRT essentially reviews footage, photographs, etc, to identify similar face maps,” he told South First.

He added that there are multiple ways these face maps could be created, like even from older photographs, but the most effective would be to take fresh facial scans.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if this was included as part of the Aadhaar process in the future, or if they start pulling this information from other databases, such as passport or visa,” said Sidharth.

However, currently, the images are compared with the database of CCTNS.

The CCTNS — the Crime and Criminal Tracking Network & System — is a national-level database of criminals being maintained by the Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India and access has been given to all state police departments, right down to the level of police stations.

It allows investigation officers to compare photographs of a suspected person, unidentified dead bodies, missing persons, and children with the CCTNS database.

The CCTNS is run and maintained by the Ministry of Home Affairs under the Central government.

The state police forces have been given access to only the data stored in the CCTNS to prevent and detect crimes.

The offender database in CCTNS is stored as per the procedures laid down in the Identification of Prisoners Act of 1920 and now the Criminal Procedure (Identification) Act of 2022.

The Hyderabad City Police mention several provisions under which the FRS is legal.

Under Section 149 of the CrPC, it is incumbent upon the police to prevent cognisable offences. “The FRS is a tool to aid the police in achieving this goal,” said the cops.

It added that the Identification of Prisoners Act of 1920 and now the Criminal Procedure (Identification) Act of 2022 confer adequate powers to the police to use tools and technologies, including the FRS, for the prevention and detection of crimes, and identification of terror suspects, missing persons and children.

The Delhi High Court, in the Sadhan Haldar Vs The State case, accepted the use of Facial Recognition Software to track missing children. “We have adopted the same technology to track down missing children,” said the police.

Section 3 of the Identification of Prisoners Act allows the police to collect the data of persons who are convicted and imprisoned for more than one year.

Now, the Criminal Procedure (Identification) Act of 2022 allows the police to collect the data of convicted persons.

Masood questioned facets of the FRS.

Among the questions he asks are those about the accuracy of the matches and if law agencies or individuals in them could misuse the system.

“We saw after the Delhi riots that many people were arrested after the authorities said they were captured on camera taking part in the unrest,” said Masood.

However, the Hyderabad City Police said that it uses the FRS to compare faces stored in the CCTNS database only if it suspects someone, or wants to check someone’s antecedents.

“The Hyderabad police earlier said that they perform random checking to identify criminals and suspects, detain them for questioning, and eventually let them go. If I am a criminal, and I am out on bail, this is my liberty and right to move into the city, you can’t say that your photo has matched with some suspects, correctly or wrongly, and you are going to detain me to question me, it’s completely illegal,” said Masood.

On the question of its illegal use, the police said that adequate precautionary measures have been incorporated in the FRS to deter any misuse.

Only authorised police personnel are empowered to utilise the tool. All such activities, along with details of such personnel accessing the database, are automatically recorded by the system.

The police also said that the FRS does not have a mechanism to automatically trace the movements and actions of the public at large.

So, the FRS may be legal. But is it required to take the consent of the person before their photograph is taken?

“Is it allowed for police to come and search your house? Yes. Is it allowed to search your house without a warrant? No. Are they allowed to stop me, search for me, and take my photo? Yes, but they have to show me a warrant. Here, they can easily obtain a warrant. That’s the problem,” Srinivas Kodali, a researcher with the advocacy organisation Free Software Movement of India, told South First.

He explained: “Consent here is a warrant. When there is a warrant, the law doesn’t allow you to oppose the warrant. You can go to court, but you still have to comply with the warrant.

Kodali added: “The police essentially obtain some powers from the district magistrate or judicial authority to perform a certain action.”

“The problem is that the police are doing it to certain classes of people without any due process. There are no rules about this now. It happens more to the poor, marginalised Muslims, Dalits, Christians, or random poor people. It’s a very inhumane discriminatory exercise. Historically, the policing was done on ‘others’. Even this will affect them more than anybody else. If you are going in a car, the driver can be subjected to this, but not you,” claimed Kodali.

He added that the police can’t randomly stop people and demand to know their identity. “You can do this at the border, but we are now witnessing it happening everywhere. From Operation Chabootra to Ivanka Trump’s visit to Hyderabad, to drug searches, the police have routinely collected data and illegally searched people,” he said.

“During protests, the police will take everyone’s photo. They will not arrest everyone that day, but do so after three to six months. All these technologies allow you to make similar profiles. These are being used on the common man,” he added.

A group of researchers at Georgetown Law School in the US obtained over 10,000 pages of information from more than 100 police departments across that country, and found that the software disproportionately affected African-Americans. “They are bad at recognising black faces,” said the study.

“This can also be extended to ethnic profiling by police within India, and be a problem with FRT where even with safeguards it can disproportionately target certain segments while at the same time not being able to recognise them correctly,” said Kodali.

The Georgetown Law School researchers also said if a training set was skewed towards a certain race, the algorithm may be better at identifying members of that group.

“We are purchasing algorithms from the West and not meant for India. The police are not going to be bothered about it. The algorithms are trained on white people. We don’t know how they will function for different ethnicities. With the Indian skin tone, the error rate will be high, and the accuracy of the algorithm will be too low,” claimed Sreekumar.

He finally said: “The questions that the police should answer start with what is the error rate of FRT? What is the size of the training data? Where did these data come from? India being a diverse ethnic country, have these algorithms been used in training data for various diverse groups?”

Jul 26, 2024

Jul 26, 2024

Jul 26, 2024

Jul 25, 2024

Jul 25, 2024

Jul 25, 2024