Published May 10, 2025 | 7:10 AM ⚊ Updated May 24, 2025 | 7:48 PM

Hut was burnt in Vadakadu Thiruvalluvar nagar.

Synopsis: There might be multiple reasons for the violence that left the Vadakadu village in Tamil Nadu’s Pudukkottai district in distress. However, it seems no concerted effort has been made to get to the fundamental, underlying cause or causes and address them for good.

Filming violence has become common of late, though not many of those videos get to the root cause of the incident.

Videos posted on social media after the clash between two communities at Thiruvalluvar Nagar, a predominantly Dalit settlement in Vadakadu village, in Alangudi Taluk in Tamil Nadu’s Pudukkottai district, too, did not shed light on the developments that had led to the violence.

Several reasons have been cited. Police said it was the fallout of a drunken brawl between two youth groups over filling petrol. Some others felt it was a land dispute, many others blamed it on caste discrimination that divides people.

The clash occurred on the night of Monday, 5 May, after the chariot procession at the Muthumariamman Temple. Besides local residents, people from other villages, too, have gathered at the temple located in an area dominated by the Mutharaiyar community.

Selvarani Kannaiya a resident of Thiruvalluvar nagar, Vadakadu

Selvarani Kannaiya, a 66-year-old Dalit, was praying after the procession along with fellow villagers. “We received word from our village that something was happening, and we should return immediately.

She left immediately. “Around 50 women and children were with me. While returning, more than 300 youth from the Mutharaiyar community passed her,” Selvarani told South First.

The figures she mentioned could not be independently verified. The woman was still in shock when she recalled the incidents of that violent night.

“They must have mistaken us for residents of another area,” she continued. Fear had by then gripped the women and children.

“After they had passed, we hid in a field. When it seemed clear and safe, we rushed back to our village,” the elderly woman said. She has been living at Thiruvalluvar Nagar. A road separated the village from the area where the temple was located.

The women still felt something was about to happen. Along with the children, they hid on the upper floor of a house that was shrouded in darkness.

Their fear came true as more than 300 youths from the Mutharaiyar community allegedly stormed Thiruvalluvar Nagar, attacking whoever came their way, setting a hut on fire, damaging houses and vehicles. They recorded their act on mobile phones and later uploaded them, with background music, onto social media.

More than 15 residents of Thiruvalluvar Nagar were left injured. Some of the assailants, too, sustained injuries. Those with grievous injuries were admitted to the state-run Medical College Hospital at Pudukkottai.

The Pudukkottai police issued a media statement the next morning. The incident had no connection with the temple festival, they said.

The violence allegedly stemmed from a drunken altercation over who should be allowed to fill petrol first at a nearby fuel station. The statement warned of action against those who “misrepresent” the incident as festival-related violence.

However, on the night of the attack, Tamil Nadu Minister S Regupathy and Tiruchirappalli Range DGP Varun Kumar met with residents of Thiruvalluvar Nagar. They acknowledged that the attack was indeed linked to a long-standing temple-related dispute and that the violence was a continuation of earlier tensions.

Whose version is true? On the first night, villagers told the minister one version of the story. The next morning, the police offered a completely different explanation.

Vadakadu is a large village, comprising 18 hamlets. While it is home to people from various communities, the Mutharaiyar, an OBC group, form the majority. Thiruvalluvar Nagar, located within Vadakadu, has been home to around 150–200 Dalit families belonging to the Paraiyar community for over seven generations.

Growing flowers and jackfruits has been the primary occupation of the residents of Vadakadu.

The “Adaikalam Katha Ayyanar” Temple, located on the main Pudukkottai–Alangudi road in northern Vadakadu, is regarded as the clan deity temple of the residents of Thiruvalluvar Nagar. Locals said there was a dispute around this temple.

Anandan A, a 55-year-old resident, said the dispute has been ongoing for 32 years.

Disputes around Adaikalam Katha Ayyanar have persisted for over 32 years.

The Ayyanar temple sits on around three acres. Initially, a few youths from another community came to play volleyball there.

“Since it seemed harmless, our elders allowed it,” Anandan told South First. Later in the 1990s, the government proposed a police station on that land. Our community protested, saying it belonged to the temple.

He claimed that the plan was dropped after a series of negotiations. But ever since, individuals from the other community have been claiming that they too have rights over this land.

Sethupathi N, a 32-year-old villager, recounted a more recent flashpoint.

Sethupathi says, “The problem isn’t about land; it’s about caste pride”

“The issue escalated significantly in 2015. Until then, the temple was just a modest structure built with sand. We decided to renovate and expand it, and when we started digging a pit for the foundation, some people from the other community objected, saying it was their play area and that the land belonged to them.”

Both sides went to court, and the case is still pending.

“If they had ownership, they would have proven it by now. The problem isn’t about land; it’s about caste pride. Their real concern is how Paraiyars can build and run a temple independently. They can’t tolerate it,” Sethupathi said.

Anandan added that more than six peace committee meetings were held to resolve the issue. “But no solution has been reached. I’ve been witnessing this tension since I was 18.”

Due to the dispute, the temple has long remained unused for worship.

In January this year, when residents of Thiruvalluvar Nagar attempted to clean the premises and celebrate Pongal, members of the other community objected, saying the land was under litigation and could not be used.

They blocked the road in protest and prevented the Thiruvalluvar Nagar residents from continuing with their rituals. As a result, the temple has effectively remained unused.

When South First visited the temple, the sanctum sanctorum was empty. There was no deity.

The Mutharaiyar community oversees administration of Mariamman temple.

With the temple remaining inaccessible, the people of Thiruvalluvar Nagar have been visiting nearby temples. The most prominent among them is the Mariamman temple, considered the main temple of Vadakadu village.

The Mutharaiyar community oversees its administration. Just last week, the temple’s annual festival was held, and ended in violence on 5 May.

MP Murugesan, a 60-year-old resident of Thiruvalluvar Nagar, said it was customary for people from his hamlet to visit the temple “while being possessed by the deity’s spirit”.

M. P. Murugesan, a 60-year-old resident of Thiruvalluvar Nagar.

“But due to the existing tension, some people from our side chose not to attend this year. However, some others, especially women, still went for the chariot procession. It was then that members of the Mutharaiyar community questioned their presence. This led to a heated argument. The women and others from our side left and returned home,” said.

Selvarani was among those who hurried home.

Contrary to Selvarani’s count of more than 300 men, Murugesan said “a few young and drunk men” from the Mutharaiyar side followed the group. He claimed they abused the group and used casteist slurs.

“Our youth confronted them and drove them out,” he said.

Sethupathi, however, added more. He spoke of two related incidents.

Hut set on fire by attackers.

“Three men initially came and they fled when confronted, leaving their vehicle behind. Later that night, after 9 pm, over 300 men came to our area, and the situation escalated. They set fire to a thatched hut, smashed cars, bikes, and house windows. More than 15 of our people sustained serious injuries, and 11 of them have been admitted to the hospital,” he said.

While residents of Thiruvalluvar Nagar made these allegations, R Rajaram from the Mutharaiyar community offered a different account. He is the state coordinator of the Naam Tamilar Katchi and is speculated to contest the 2026 Assembly election from the Peravurani constituency.

R. Rajram, State coordinator of the NTK

Rajaram said the incident was not caste-related. “This is not a caste clash. Many people are speaking without knowing the facts. This was a premeditated attack on our community,” Rajaram told South First.

However, his version contracted Naam Tamilar Katchi coordinator Seeman’s 7 May statement that the Vadakadu incident was a “caste clash”. Seeman demanded that the Tamil Nadu government take immediate action without concealing the facts.

Rajaram claimed that the incident was an offshoot of an assault by Dalit men on a group of Mutharaiyar community members. He alleged the attack occurred on Monday when the Mutharaiyars were passing through Thiruvalluvar Nagar on their way to Therkkupatti.

He claimed that those who attempted to rescue the injured were also assaulted. “Even the police were complicit in this,” he added.

Rajaram went further to allege that Vadakadu Inspector A Dhanabalan deliberately restrained members of the Mutharaiyar community, allowing Dalits to attack them with machetes. “The injured victims told us about this incident,” he claimed.

Inspector Dhanabalan has since been transferred to the compulsory waiting list.

On the other hand, affected residents of Thiruvalluvar Nagar also accused the police. They said the police arrived only after 30 minutes of the attack on Monday night.

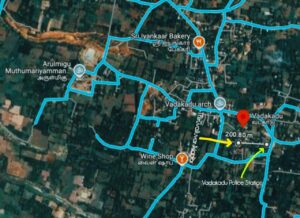

The Vadakadu police just 200 meters away from Thiruvalluvar nagar.

Marikannu Selvarasu, a 60-year-old resident, said she had to wait for an ambulance for three hours to shift her grievously injured son-in-law.

Sethupathi said his villagers had not gone to the area of the Mutharaiyar community and attacked them. “They entered our locality and launched the assault. Yet, only 13 of them have been arrested, and the instigators are still roaming free. Worse, the police are now attempting to file cases against us, the victims,” he claimed.

He further accused the local MLA and Minister, Siva V Meyyanathan, of influencing the police.

Meyyanathan Siva V, Minister of Backward Classes Welfare of Tamil Nadu

“Meyyanathan belongs to the Mutharaiyar community. For him, 6,500 Mutharaiyar votes matter more than 500 Dalit votes,” he claimed.

Rights activist Evidence Kathir, aka Arokiasamy Vincent Raj, said the mob that attacked the village was armed with sticks and stones. “Only 12 people have been arrested, and they’re all from different villages. This looks like a deliberate strategy to present a united front and project collective opposition to Dalits,” he opined.

He said the attack on homes was not to destroy property but to terrorize people. “This isn’t just arson — setting fire to homes reflects the intent to harm lives. Yet the FIR is extremely weak,” he said.

Evidence Kathir visited the affected area

Only four sections of the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act have been applied: For casteist slurs (Section 3(1)(r)), damaging Dalit property 3(2)(3)), and damaging land 3(2)(4)).

“Six Dalit women were harassed and subjected to caste abuse. But appropriate sections haven’t been invoked,” Kathir alleged.

“No case has been registered over the burning of Dr BR Ambedkar’s portrait,” Kathir pointed out. “Neither has IPC Section 325 (grievous hurt caused by a group) been included. All of this shows just how weak the FIR is.”

Kathir also noted that 10 people were booked based on the complaint from Dalit residents, while a counter-complaint led to FIRs against nine Dalits. “This reflects an attempt by the state to portray both sides as equally culpable — a vote-bank balancing act rather than justice.”

Murugesan said no senior government official had visited them. “They’re dragging their feet instead of launching a proper inquiry because we are just 200 Paraiyar families,” he said.

South First visited the petrol station, where the police said the issue started. The staff was visibly frustrated when asked about the brawl at the station.

“Don’t drag us into this. We have no connection with what happened, and we don’t know anything. The police asked for CCTV footage, and we handed it over to them,” they said.

Inspector Dhanabalan still insisted that the conflict began at the petrol station.

Kathir also questioned the police narrative. “The FIR mentions a petrol bunk as the site of the initial incident. But no one from either side has referred to any petrol bunk. If it happened there, shouldn’t it be properly documented in the FIR?” he asked, suggesting the police were presenting a manipulated version of events.

banner with caste identities

At the Vadakadu neighbourhood, banners screaming caste identity and religious posters were seen on either side of the about one-kilometre walk to the Mariamman Temple from the Vadakadu Arch.

Hundreds of men had gathered at a community hall for what seemed like a closed-door meeting.

“Only those who are Ambalathaar (Mutharaiyar) from Vadakadu can go inside. No one else is allowed,” a man posted outside said.

Many of those gathered appeared angry with journalists, and they blamed the media for amplifying the situation.

Even as South First was at the scene, Minister Meyyanathan arrived for the first time, two days after the violence. He spoke to the men at the meeting. He has yet to visit the village where people were attacked.

Minister Meyyanathan leaving from Mutharaiyar community meeting

Interestingly, he took a different route rather than the main road through the Vadakadu Arch, which raised eyebrows.

Despite his arrival, no one apart from the Mutharaiyar community was allowed inside the hall. Some 20 minutes later, the Mutharaiyar members, who had been hostile to the media, encouraged journalists to interview the minister.

Meyyanathan, however, declined to speak and proceeded to Thiruvalluvar Nagar, his second stop.

South First had earlier witnessed the strong resentment against Meyyanathan among Dalit residents in Thiruvalluvar Nagar. When he finally showed up after two days, locals confronted him with questions.

“Why did it take you two days to visit your constituency? Are you siding with them? Are the arrests of our youth happening on your instructions?” they asked.

Minister Meyyanathan replied in the negative. “I have never intended to hurt or target anyone. Even if someone curses or hits me, I won’t retaliate. I follow Periyar’s path. I don’t believe in caste or religion,” he claimed.

He nodded in agreement when the community pleaded not to arrest more youth.

However, Inspector Dhanabalan earlier confirmed that one person from Thiruvalluvar Nagar had already been remanded, and cases have been filed against five more individuals. “We will be arresting them soon,” he said.

Several young men from Thiruvalluvar Nagar have reportedly fled the village, fearing arrest. Meanwhile, those injured in the hospital remained under police surveillance, adding to the prevailing sense of unease and mistrust in the community.

Most of these young men are either college students or degree holders. The looming threat of arrest has now cast a shadow over their futures.

Kathir stressed that the conflict can’t be dismissed as a mere temple entry dispute.

“This is about land owned by Dalits. The dominant caste group initially sought permission to play volleyball on it, and that was granted. Later, a dispute over ownership emerged. When the Dalits asserted their rights, they were denied entry into the temple, sparking the conflict.”

“I see this as a politically motivated move,” he said.

“Tamil Nadu isn’t an anti-caste state. It’s just anti-Brahmin. The DMK projects itself as beyond criticism, but only leftist and Dalit movements are consistently fighting caste-based injustices like these,” the activist said.

He referred to an allegation by the Thiruvalluvar Nagar residents that Meyyanathan applied pressure to protect members of the Mutharaiyar community. “This could explain the sudden transfer of Minister Regupathy’s portfolio.”

“People here talk about caste discrimination by Brahmins in big temples like Meenakshi Amman Temple. But no one talks about the untouchability and caste violence in village temples,” Kathir said.

He added that in just the past four years, more than 45 caste-related temple conflicts, including at least 40 forms of untouchability, such as Dalits being denied entry to temple sanctums or barred from participating in temple festivals, have been reported.

“A government shouldn’t engage in caste-based politics. It should govern for the people,” Kathir said.

“Back in 2018, before coming to power, Chief Minister MK Stalin promised a law against untouchability. Now he says there’s no need for a special law. Instead of vote-bank politics, we need people-centric governance,” he added.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).