Published Sep 06, 2024 | 12:56 PM ⚊ Updated Sep 06, 2024 | 2:29 PM

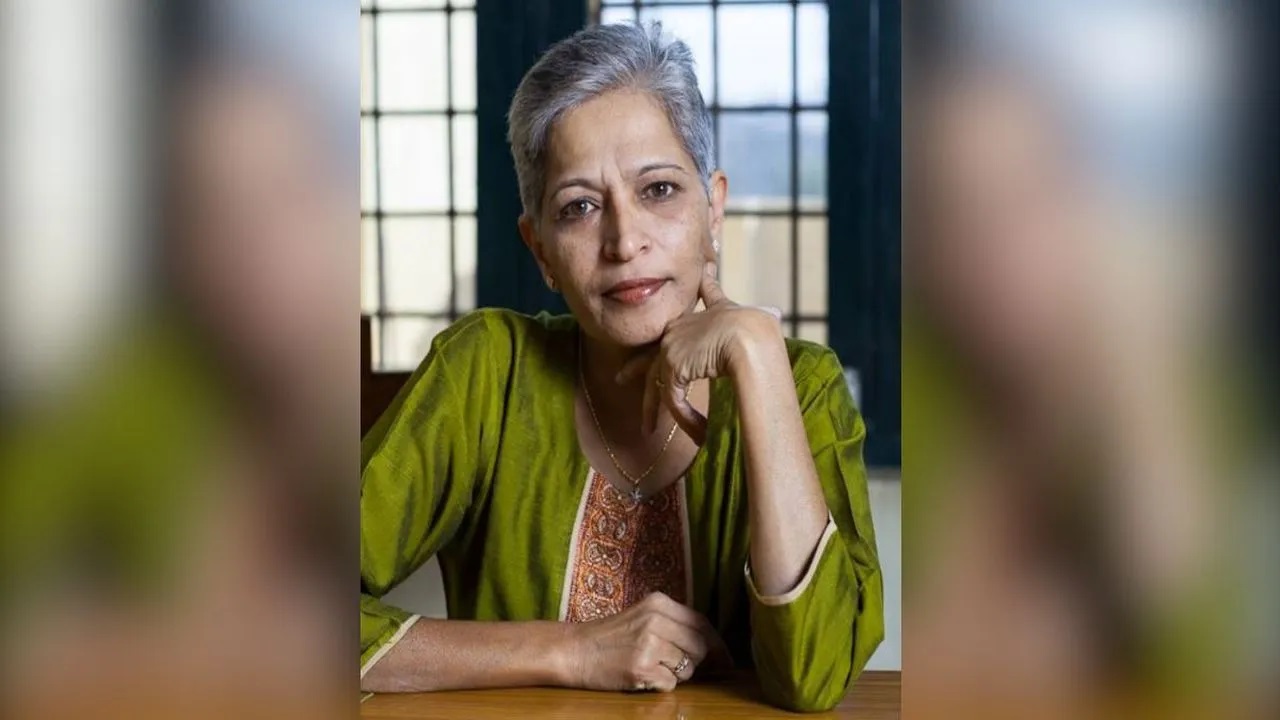

Gaurl Lankesh (29 January 1962 – 5 September 2017).

I first met Gauri Lankesh when I was an undergraduate student at St Aloysius College, Mangaluru, in 2003. She was on our campus as the chief guest of a seminar held by the social work department.

Though I hadn’t read her writings, I was impressed by her clarity of thought when she spoke of social justice and was moved much by the affectionate way in which she spoke to all of us. Our brief interaction that day ended with her writing her postal address in my notebook. “Keep in touch,” she said.

Till some time in 2005, I wrote to Gauri once, responding to the news, reports, etc., published in the weekly which she edited. Gauri responded to almost all my letters. Those brief and warm exchanges came to a still during the monsoon of 2005, as I got absorbed in my world.

In 2009, when I was working for The Hindu in Mangaluru, I received a call from an unknown number while I was filing a report one afternoon. The voice from the other side said, “Hello Samvartha, this is Gauri Lankesh.”

She had called to pat me on the back for the report, ‘Hindutva people attacked us, Hindus saved us’.

The report she mentioned was on a minor riot in Kaup, which erupted after the Hindu Samajotsava in Mangaluru. The mosque in Kaup was harmed, and some Muslims were attacked. Among them was a group of Muslim boys returning from a cricket tournament.

In an interesting twist, a few Hindu men and women bravely battled the Hindutva goons and rescued the Muslim boys. When I met those boys at a hospital later, they recollected the incident and their captain said, “Hindutva people attacked us, Hindus saved us,” which became the headline.

Gauri wanted to honour those who fought off the Hindutva goons and saved the lives of those boys. She had called me to help her get in touch with those men and women. (Gauri translated the report and carried it as a part of her editorial the following week).

During that noon’s talk, there was much warmth in Gauri’s voice that I believed she remembered me from my teenage days when I first met her and also wrote letters to her. But it wasn’t so.

In 2014, Gauri and I met in Mysuru for a seminar on Sufism. That evening we roamed the streets, endlessly talking about our movements, literature, journalism, common friends, and our lives.

Until that day, whenever I had met Gauri, it had been either at an event or a meeting, or a protest, with not much time and space for any personal conversation. That evening’s long conversation turned our camaraderie into friendship.

During the course of the conversation, I recalled a letter she had written in response to mine. Gauri gulped down the whisky she had sipped to blurt out, “Are you the same boy?”

When I smiled in the positive, Gauri was apologetic. “I was not comfortable writing in Kannada those days, though I could speak and read quite well in Kannada.”

She followed it up with anecdotes of her struggle during her initial days in Kannada journalism, which made us have a good laugh.

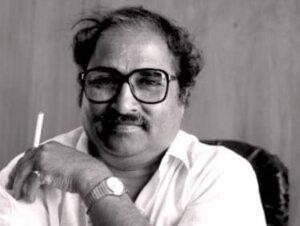

Gauri, who had been working in Delhi with an English media house, returned to Bengaluru in 2000 when her father, a giant of a writer and journalist, P Lankesh died. She decided to quit her job and took over as the editor of the weekly, Lankesh Patrike, which her father used to edit.

P Lankesh (Photo by Basavaraju Megalakeri)

Until she took charge of Lankesh Patrike, she had not shared a deep bond with Karnataka and the lives of its people. Moreover, she hardly could fluently write in Kannada.

The huge fan following that Lankesh Patrike had earned because of Lankeh’s rich prose, looked at Gauri sceptically and doubted her ability to carry forward the legacy of Lankesh and Lankesh Patrike.

But over the years Gauri surprised all — and probably herself too — by becoming a prominent ‘Activist-Journalist’ (as she liked to refer herself) in Kannada, writing prolifically in Kannada and making speeches in unwaxed Kannada.

The last 17 years of Gauri’s life, which she spent in Karnataka, working as a Kannada journalist, involving herself in social movements, and engaging personally with the lives of Kannada people, defines Gauri the best. The message of Gauri’s life lies in those 17 years for they tell the tale of her BECOMING.

In 2000, when Gauri returned to Karnataka, she could hardly write and speak Kannada fluently. Her editorials of those days and the letters she wrote in those days stand testimony to her lack of language skills.

Gauri Lankesh in 2012. (Photo by Hari Prasad Nadig/Wikimedia Commons)

Those days, she was just a liberal humanist. But things changed quickly. As she became more involved with the lives and issues of Karnataka, her politics became sharper.

If learning to write in Kannada marked the first step of Gauri’s becoming, the second major step in her transmogrification came with her being one of the founding members of Karnataka Forum for Communal Harmony (Karnataka Komu Sauharda Vedike), which was born in 2002, in response to the Gujarat communal violence.

Soon the RSS and BJP announced to make Karnataka “another Gujarat.” The aim, they announced, is to make the syncretic Bababudangiri the Ayodhya of the south. This was met with strong resistance by the Karnataka Forum for Communal Harmony where many, including Gauri, were jailed.

The movement to preserve the syncretic culture of Bababudangiri shifted gears in the activist life of Gauri, brought her closer to the activist circles in Karnataka, and fine-tuned her politics.

Around the same time, the Naxalite movement found strong ground in Karnataka. In 2004 she was one of the journalists who were invited by the Naxalites for a press meet in the Western Ghat forest. During this visit, she met her college senior Saketh Rajan alias Prem alias Saki who was leading the Naxalite movement in Karnataka.

The author with Gauri Lankesh in 2003. (Supplied)

Through her interaction with him and others made her see the lives of the Naxalites closely. She developed great respect for all those people who had left all the comforts and luxuries of life and lived under difficult circumstances inside the forest. The commitment they had for the values they believed in and the dream they had for the world humbled her.

But that did not eclipse her core value of non-violence. She decided to act as a mediator between the Naxalites and the government to arrange for a meeting between the two and resolve the issues. Both parties agreed but the government acted prematurely and assassinated Saketh in early 2005.

Angered, Gauri got onto the streets to condemn the government. This earned her the tag of a Naxalite sympathiser when all she desired was peace and resolving of issue without arms!

In the following days, she along with the freedom fighter HS Doraiswamy, started the Citizen’s Initiative for Peace which mediated between the Naxalites and the government and brought back many Naxalites to the mainstream.

Noor Sridhar, one of the Naxalites who came back to the mainstream, in an article on Gauri written after her assassination, said that the Naxalites have been fonder of Gauri than Gauri being fond of them. His words punctured the belief of the masses — or what they were made to believe — that Gauri Lankesh was a Naxalite sympathiser.

Shridhar, in the article, observed that though Gauri was in solidarity with the communists, was never a communist, though she had sympathies for the Naxalites, she never endorsed their methods, and though she associated herself with the Dalits and the Dalit movement, she was never an Ambedkarite.

Continuing his observation, he said Gauri’s solidarity was with values she believed in and she always saw the limitations of organisations and institutions. Probably it could be the reason why she never became an active member of any organisation. Her participation was purely value- and agenda-based.

In a personal conversation in the days following Gauri’s assassination, social activist K Phaniraj recollected how Gauri was not familiar with the fractions within the communists and the several parties that burst out of the Communist Party of India.

It seemed, on learning how there are over 64 such organisations in existence, Gauri reacted with a, “Whatever.” That “whatever” was not dismissive but an “I cannot be bothered” in nature.

This ‘not being bothered’ did not mean she did not care. It only meant she did not want to focus on it. Instead, focusing on the possibilities of a united force to make the world stand on its legs was important for her.

Her solidarity with every movement that works for justice underlined this quality of hers. It reflected in her efforts to bring together the ‘red’ and the ‘blue’. This effort was not a strategic position or move for her but something she believed with all her heart.

During the Chalo Udupi rally taken out in October 2016, it was decided that only blue flags would be used by all. But on the day of the rally, many organisations that showed solidarity brought their party and flags.

I witnessed Gauri politely requesting those organisations to fold their flags and keep them inside. It demonstrated how she viewed herself in movements — not as a leader but as a cadre.

Her action also reflected a shift that many saw in her ideological position. By then, ie. 2016, she had begun to absorb Ambedkarite thoughts and was preferring ‘blue’ to ‘red’ though she wanted both these colors to come together as a united force.

Gauri had not read Ambedkar till some years before her assassination. But when she read, she let Ambedkarite thoughts seep into her and she also expressed her regret for not having read Ambedkar for long.

It is not that she was not sensitive to the cause of Dalits before reading Ambedkar. But her Dalit consciousness had not baked in a strict Ambedkarite sense of it and was still within the large framework of human rights and civil rights.

The birthday gift I received from her in the year of her death was the biography of Periyar. That sort of hinted at the path she was progressing.

The last time I met Gauri was at the Chalo Udupi rally. It was just a few days after I had returned from Jammu & Kashmir. I was sent to J&K for a book project and my visit coincided with the uprising that followed the assassination of Burhan Wani.

Gauri was keen on knowing what I had seen and heard. She insisted I that took her for a good fish meal, and I did. As we drove and later had lunch at a small hotel in Udupi, she heard with utmost curiosity the stories of my travel and meetings in J&K.

In the end, she asked me if I would be willing to go to Kashmir with Shivasunder, a senior thinker and activist, for a series of reports for her weekly, Gauri Lankesh Patrike. I immediately agreed.

After some weeks when I reminded her about the plan, Gauri said, “Shivasunder seems to have other commitments. We both can go together.”

A month later Gauri called me at her usual time — when both the needles of the clock are the closest to one another. She had just completed reading Basharat Peer’s book, Curfewed Night: A Frontline Memoir of Life, Love and War in Kashmir.

She wanted to thank me for suggesting her the book. I suggested some more books on Kashmir to her and she carefully made a note of them. Her excitement showed how the Kashmir issue was not a major preoccupation for her until then and how slowly it was becoming one. That is exactly why she was planning a trip to Kashmir with this young friend.

Before we could carry out our plan, demonetisation hit the circulation of Gauri’s weekly and she was in a financial crunch. It made her write columns for other publications. Eventually, even those columns stopped. The space for liberal radicals was swiftly closing down.

A Revathi featured on the cover of her autobiography.

Gauri herself spoke of the financial crunch when she called a month before her assassination. She had called to say how a particular article by someone from J&K thrilled her and how badly she wanted to meet the writer.

“We can meet when we go there,” I told her. In response, she explained the financial matters saying, “Let me recover a bit and then we can go.”

A month later on 5 September 2017, Gauri was assassinated and the dream of our Kashmir visit also died with her.

Soon after her assassination, I heard that she had made many plans earlier that could not materialise because of her financial crunch.

Ramesh Aroli had translated Gudipati Venkatachalam’s novel ‘Maidaanam’ which she was to publish. Gauri had published A Revathi’s autobiography, The Truth About Me: A Hijra Life Story in Kannada.

In that list was also a translation of Curfewed Night which I was to do. All of these had been delayed because of demonetisation’s effect on Gauri.

When a person like Gauri dies, several dreams die, and though movements don’t die, they feel a jolt and lose some energy.

Kavitha Lankesh with her sister Gauri Lankesh (Supplied)

The day after her assassination, like in many places across the country, a protest was held in Udupi also. More than anger and shock, there was a feeling of deep sadness in the air. For everyone, the loss felt personal. A Dalit activist held me tightly and wept uncontrollably saying, “Now who will care for us?”

Gauri’s life coming to an abrupt end not only shook but also made many feel orphaned.

The same Dalit activist went on to say, “Now who will give space to our issues in media!” Gauri did not believe in becoming the voice of someone else but always made sure she listened to the voice of the people and within her means did whatever was possible to amplify those voices, through her tabloid, through her publication, etc.

With her death, spaces also shrunk by a small margin.

A week after Gauri’s assassination a huge protest was held in Bengaluru. Revathi, whose autobiography Gauri had published and whose next book Gauri was to publish, was on the stage representing the community of sexual minorities. Akka (elder sister) was in tears when she embraced Gauri’s mother Indira and sister Kavita Lankesh.

It was learnt that the members of the sexual minority community in Bengaluru begged on the streets to raise money for organising the protest event. It showed Gauri’s close association with the sexual minorities, which was hardly known to many.

After Gauri’s assassination, an article published on a Kannada website revealed the backstory of her association with the sexual minorities.

During the early days of Gauri’s editorship at Lankesh Patrike, one of their reporters filed a slightly derogatory story on the people from the sexual minority community. A case was filed against the publication.

‘An ambulance in the name of Gauri Lankesh to help the needy and downtrodden’ (Twitter/@KavithaLankesh)

The case was being fought by one BT Venkatesh. He once took Gauri to meet the members of the sexual minority community, and that meeting became the beginning of her association with the community. From then on, she became a part of their struggles, social and political. Gauri became akka to the community.

This gesture of affection revealed Gauri’s relationship with the people of sexual minorities was not just as a reporter grounded on certain political correctness but extended to a personal relationship with them. That is exactly why the stigmatised, excluded, and abandoned community cried loudly in Bengaluru on 12 September 2017, “I am Gauri.”

In the last 17 years of her life, Gauri became a lady of movements, as a journalist, and through her active participation in different movements for rights and justice. It was a long journey from where she had begun in 2000 as a person of broad liberal humanistic values.

She also was aware of the change she had undergone — becoming an activist, learning Kannada, internalising Ambedkarite values, developing sensitivity towards sexual minorities, coming to understand the Naxalite struggle, arriving at a solution for the Naxalite problem, working towards understanding the Kashmir struggle, etc.

Probably her own life taught her the possibility of the change human heart and intellect can go through when they face reality and truth. Maybe that was the reason for her immense faith in dialogue.

Even when she was trolled on social media by people half her age and younger than that, she engaged with them and dialogued with them.

Rahul Gandhi walks with slain journalist Gauri Lankesh’s family during tthe Bharat Jodo Yatra. (Supplied)

In all possibilities, it is because of her own becoming that she could invest faith in the possibility of those ‘misguided children’ of hers (as she called those trolls who wished her death) becoming better, socially sensitive, and politically conscious humans.

At the same time, through her becoming she gave us the message of her life: humans can change for the better and society too can change for the better through those changed humans.

It must also be said that Gauri is also a product of the times in which she lived. The pressure of history was such that Gauri became Gauri. But it is not the call of the times that alone makes a historic figure like Gauri but also how they respond to the times. As much as Gauri was shaped by the times, the times she lived also got shaped by Gauri.

Gauri emotionally adopted Kanhaiya Kumar, Jignesh Mevani, and Umar Khalid as her sons. All three are similar in one way, yet different ideologically. Gauri adopting them shows the vastness of her and her desire for the convergence of all life-affirmative forces.

At times when Gauri would refer to Kanhaiya, Jignesh, and Umar as her sons, I would playfully ask her why wouldn’t she adopt me as her son and notoriously asked for a T-shirt when she bought one for them.

Gauri would know that I was pulling her leg and would respond saying, “You have been adopted by me long ago. These are new ones.”

It was not an intelligent answer to our notorious remarks but an honest answer. She had always treated me and many like me as her children.

I can never forget how once she called me to ask how I was doing after she discovered (through my couplets posted on social media) that I had separated from a dear one, and was heartbroken. She consoled me like a friend and asked me not to spend much time over lost love because that would eat up the time I could dedicate to finding new love.

The concern was genuine and each word spoken was honest. A few months before her assassination I had messaged her about the fellowship I had received to make a film on mental health and that night, late night, she had called to discuss her thoughts around mental health, depression to be specific, and to suggest what possibilities could be explored in the film I was supposed to make.

I am recollecting some of these very personal matters just to say that Gauri saw me and many like me not just as comrades of concern but as fellow humans, as friends, who meant a lot to her beyond social-political movements, for the thoughts and ideas that we shared, etc. She cared for all the humans she was associated with. There was immense truth in her concern for her fellow beings.

Gauri was like a mother, friend, and guide all at the same time.

Commenting on one of Gauri’s social media posts, a young boy not only threatened to kill her but also announced that he would celebrate her death by distributing sweets in his neighbourhood.

Gauri’s response was unimaginable: “Don’t bother your parents by asking them for money while you are still dependent on them financially” she said, and asked the boy to share his bank details so that she could transfer some money to him to buy sweets on the day of her death.

These were not her clever ways to win an argument or to end an argument. This is what she was — someone who cared for others, for the world, even when the gun was pointed at her!

Gauri would publish some of my translations in her weekly and tell me after the week’s edition would be out. Once when I told her she had to get prior permission before publishing them . She laughed loudly, asking me to repeat myself. I felt so embarrassed that I shut my mouth first and then opened it only to join her in laughing.

She would publish my translations without my permission because she believed that among friends it is okay to take such liberties. Moreover, she wasn’t making any profit from publishing to share any percentage of the profit. But whenever we met, she treated me and, on my birthday, I could rightfully demand a gift.

Once Gauri called me an hour before the weekly was to go for print, asking me to translate a poem “asap.” It was the poem by Hussain Haidry which had gone viral. I was at an ice cream parlor with a friend when she called. I ended up translating the poem on a paper napkin.

When I called her once done with the translation, she quickly typed down the translation. Then immediately she said, “Now listen” and read out her translation of Abul Kalam Azad’s poem. It was a poem written in response to Haidry’s poem. She was to carry both poems in her coming issue.

Though Azad’s poem appeared to counter the poem of Haidry at one level, to Gauri they were complementing poems. Moreover, even if it was countering, she would still carry it because Gauri always had space for dissent, and looking through her eyes, those two poems were not contradicting but were in conversation. It was a dialogue!

Once an activist was expelled out from the Karnataka Komu Sauharda Vedike. I told Gauri that the abandonment was not acceptable to me because I believe excommunication is a Brahminical idea. I guess she hadn’t given it much thought until then. When I voiced my feelings, she immediately said, “Yes, you are right. I will see what can be done.”

She told me she would not just speak to the core committee of the organisation but also speak to the excommunicated activist. There was no space for abandoning and excommunicating in her world, and even those who made mistakes, she felt, did deserve a second chance, a chance to correct themselves.

My former colleague and friend Sudipto Mondal remembered how he once opposed (in an article) Gauri on ideological grounds and thought it would make Gauri break ties with him. But he was in for a surprise. The next time the two of them met, Gauri spoke to him with the same affection and introduced him as her “son” to a friend.

Gauri believed in and lived what Makhdoom wrote:

Hayaat leke chalo kaayenaat leke chalo,

chalo toh saarey zamaaney ko saath leke chalo.

That night in Mysore, when Gauri and I had the longest conversation ever, she had asked me if I had read her mother’s autobiography. I hadn’t. Gauri promised to send me the book but forgot to keep the promise.

Later when I read the book, I called Gauri to playfully tease her about her unkept promise. She laughed and then asked me what I thought of the book. The outstanding book chronicles the coming of age of both Lankesh and Indira Lankesh.

In my reading of the book, I saw how the coming of age of a man is more than often individualistic and personal success/achievement-oriented, while the coming of age of a woman is more than often a collective growth, and the success is measured through the contribution made to others lives, especially those around them.

Gauri liked my reading of the book. In the conversation around her mother’s book, I told Gauri that she should write her autobiography because that would give us a third dimension to the life of her father. She dismissed the idea. Had she written would it give us a third dimension to the life of Lankesh.

But I am sure it would still be a story of coming of age where growth is collective and life, cooperative.

Rest in power, Gauri!

(Samvartha Sahil is a writer, translator, and teacher of screenwriting. An alumnus of Jawaharlal Nehru University and the Films and Television Institute of India, he has authored five books, which include the translation of the poetry collections of Nagraj Manjule, Jacinta Kerketta, and Yogesh Maitreya. Views are personal. Edited by Majnu Babu).

(South First is now on WhatsApp and Telegram)