Published Mar 04, 2025 | 5:40 PM ⚊ Updated Mar 04, 2025 | 8:00 PM

Synopsis: The upcoming Karnataka budget has attracted nationwide anticipation, with many critics of the Congress government hoping it will expose the financial strain caused by its welfare schemes. This opposition reflects a broader resistance to welfare policies, often driven by capitalist and caste-based biases, despite these schemes providing essential relief to a majority of the state’s residents amid rising costs, unemployment, and growing inequality. (This piece was originally published in Kannada on eedina.com)

This week, all eyes are on the Karnataka budget. State budgets rarely capture national attention, apart from when a particular scheme or programme sparks discussions beyond state borders. But this time, there is an unusual level of curiosity nationwide about the 7 March presentation.

Rather than just curiosity, it may be termed a malicious anticipation.

There are quite a few who believe that the Congress has tied itself up in knots with its guarantee schemes.

They wait for this government to collapse under the weight of its own promises. They hope that the financial burden of these guarantees will stifle developmental activities, dragging the government into disrepute.

This isn’t merely about opposition parties; it reflects a deeper societal aversion to the concept of a welfare state. That aversion isn’t confined to just the opposition – it is deeply ingrained across certain sections of society.

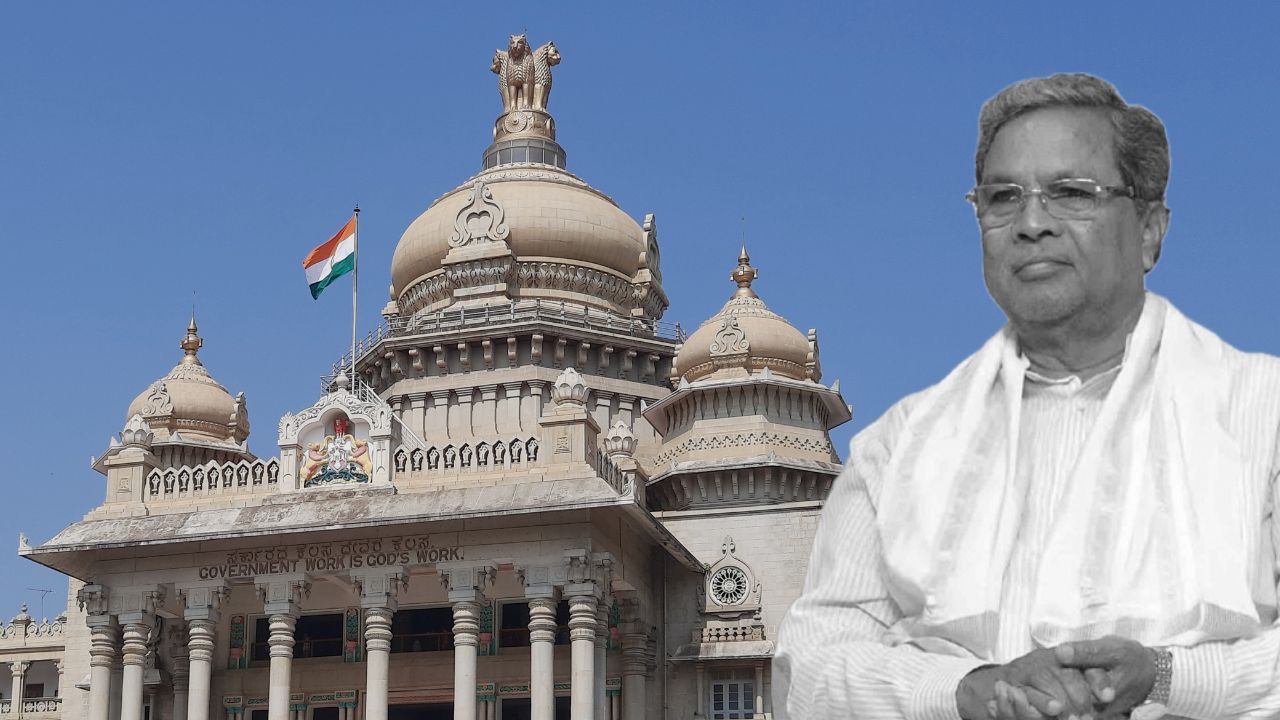

With that same mindset, many have fixated their gaze on this year’s budget. As Chief Minister Siddaramaiah prepares to present his record 16th budget as Finance Minister, many hope it will expose financial mismanagement and tarnish his credibility.

They expect revenue deficits and visible cuts in infrastructure spending. They want the government’s finances to be so strained that it cannot even afford to fill potholes – so that every bump on the road reminds people of the guarantee schemes, making them curse these policies.

They want to see reduced allocations for Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe sub-plans (SCP/TSP). They want the simmering discontent within these communities – over funds being redirected toward guarantee schemes – to erupt into full-blown outrage…

Thus, those eagerly waiting to oppose the guarantee schemes are watching the budget with anticipation.

However, this deep-seated resentment isn’t limited to just the guarantee schemes. In reality, this mindset extends far beyond – to reservations, subsidies, price controls, free ration for the poor, government-funded education, public healthcare, and public transportation.

Essentially, any welfare initiative is unpalatable to these groups.

A veiled but persistent hostility toward all such social welfare programmes runs through certain sections of society. At times, this resentment even rears its head openly, with no hesitation or shame.

This kind of antagonism has multiple roots. Some of its origins lie in a ruthless capitalist, pro-corporate ideology, whilst others are deeply entrenched in feudal and creed, caste-based hierarchies.

As a result, any socio-economic progressive policy is met with the same resistance. But that is an entirely different discussion.

So then, should the guarantee schemes not be criticised at all?

Of course, they should be critiqued and debated. It is essential to analyse the pros and cons of these schemes.

However, such discussions must be conducted with balance, objectivity, and a rational mindset. Before critiquing them, we must first understand why programmes like guarantee schemes are necessary in the first place.

Looking at the trajectory India has followed over the past few years, we can identify several key factors that have significantly impacted people’s lives:

Despite these glaring issues, there is a serious lack of in-depth studies on the real impact of these developments on the middle class, lower-middle class, and poor communities.

Rising costs of living, a persistent sense of insecurity, the sharp decline in trust in government schools and hospitals, large-scale migration from rural areas to cities, the stagnant progress of northern states like Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, and Rajasthan – often labelled as “BIMARU” states – the widening chasm between the wealthy and the common people, the erosion of social values, and the deterioration of social harmony – all these are critical issues staring us in the face.

For the common people, the lower classes, and marginalised communities, the impact of rising prices and interest rates continues to intensify.

For many, daily survival has become an ordeal. The Union government – directly or indirectly responsible for much of this – has failed to introduce any meaningful measures or policies aimed at ensuring the holistic development and dignity of the people. Instead, it has wasted time with symbolic gestures, hollow policies, and performative governance.

Against this backdrop – and as a response to the political necessity of electoral success – the guarantee schemes emerged. For people who had been left burning in the fire of economic distress, these schemes came as a much-needed shade of relief.

As the name suggests, guarantee schemes are designed to offer immediate assurance to the common people and ease their financial burden to a certain extent, instilling a sense of hope in their lives.

These schemes cannot be viewed in isolation from long-term policies and economic strategies. Instead, they must be seen as an essential part of social security and a dignified life.

How beneficiaries utilise the advantages of these schemes is ultimately their responsibility.

However, so far, there is little evidence or real-world examples to suggest that people are misusing these schemes.

In contrast, there is widespread testimony from beneficiaries about how these programmes have positively impacted their daily lives.

If we set aside the cynicism of the upper-middle class and genuinely listen to the experiences of lower-income communities, we will find countless inspiring and hopeful stories unfolding before us.

Despite all of this, it is neither unreasonable nor unnecessary to critically evaluate and refine these guarantee schemes with a balanced mindset.

Take, for instance, the Gruha Jyothi scheme. Electricity usage is one of the fundamental necessities of modern life. If industrial and commercial electricity consumption reflects a state’s economic and business activity, household electricity usage serves as a mirror to the living standards of its people.

While seasonal and natural variations directly impact electricity consumption, it still remains an important metric in assessing overall quality of life.

In general, the more financially well-off a household is, the greater its use of electrical appliances, electronic gadgets, decorative lighting, multiple rooms, and bathrooms, leading to higher per capita electricity consumption.

To illustrate this, let’s consider an example:

Providing up to 200 units of free electricity – based on the previous year’s average consumption – to a well-off family with two working members and a stable financial background does not serve as an economic relief for that household.

Instead, it acts as a bonus for them.

In contrast, a family of four members in a city like Bengaluru, earning around ₹40,000 per month, tends to consume significantly less electricity on average.

As a result, while lower-middle-class and poor families receive fewer free electricity units (around 70-120 units), the upper-middle-class and wealthy households benefit disproportionately – sometimes receiving up to 160-190 free units.

In a modern society, ensuring free electricity for lower-income households – without making it a financial burden – is undoubtedly a progressive idea. However, the intended objectives of the scheme are not fully realised when implemented in this manner.

This raises an important question: Shouldn’t government schemes be designed with clear income thresholds? Shouldn’t policies be structured so that they benefit those who truly need them the most?

If the guarantee schemes had been formulated with these considerations in mind, they would have been far more meaningful and effective.

To address such shortcomings, the government should have taken steps to identify the right beneficiaries and tailor specific schemes accordingly.

It is evident that the design and execution of these guarantee schemes have not undergone the level of critical analysis and deliberation they should have.

For instance, there could have been 100 free units to all and as the consumption goes beyond a progressive tariff slabs might have been introduced. The government can still come up with such positive interventions.

While fine-tuning the guarantee schemes is one approach, another crucial aspect is to fundamentally restructure the flawed tax distribution system, which currently undermines the interests of states like Karnataka.

Karnataka, like several other states, contributes an enormous share of tax revenue to the Union government yet receives only a fraction in return. This is nothing short of exploitation. The states facing this injustice must seriously and collectively deliberate on ways to rectify this imbalance.

In a federal system, it is natural that some states are more prosperous and economically advanced than others. It is both a constitutional and moral responsibility for these states to contribute toward the development of less-developed regions by sharing a portion of their tax revenues.

However, there needs to be a serious re-evaluation of how much of this revenue-sharing is fair.

Take Karnataka’s case – the state contributes ₹4 lakh crore in taxes to the Union government annually but receives only ₹52,000 crore in return. Even to receive this amount, the state is forced to plead before the Union government.

This is not how a true federal structure should function.

Karnataka must not be reduced to a state that pays ₹1 in taxes and is left begging for 15 paise in return. Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra are also facing similar gross injustices in taxation. These states must raise their voices firmly against this disproportionate distribution of financial resources.

The Union government should not act like a feudal overlord sitting atop the states, dictating terms. Instead, it must behave like a responsible custodian, ensuring that resources are efficiently allocated for national development.

However, under the current federal structure, regardless of which party holds power at the centre, authoritarian tendencies are becoming more pronounced, rather than a trust-based approach. The Union government has started behaving like a supreme emperor controlling vassal states, implementing destructive policies and practices that undermine the autonomy of states.

This must change.

The tax revenue collected from states should be transparently allocated to sectors like education, defence, and healthcare.

Furthermore, the Union government must provide a detailed breakdown to states, especially high-tax-paying states, explaining exactly how every rupee they contribute is being utilised to uplift the quality of life of Indian citizens.

The Union government must also be financially accountable to the states, particularly to those contributing a larger share of national revenue.

If Karnataka and similar states begin to feel that their tax money is not being used effectively for national development, they must have the constitutional freedom to raise objections and seek legal and democratic avenues to correct this injustice.

Karnataka’s political leaders must rise above party lines and fearlessly negotiate with the Union government on these critical issues.

Whether they are Members of Parliament representing the state or ministers at the centre elected from Karnataka, they must remember that their duty is not to serve the agenda of a political party but to safeguard the interests of Karnataka.

They must not betray this responsibility.

(This piece was originally published in Kannada on eedina.com and has been translated and reproduced with permission. Translated and edited by Dese Gowda)