Published Nov 02, 2025 | 8:00 AM ⚊ Updated Nov 02, 2025 | 8:00 AM

Mari's films, including Bison, subvert the established patterns, methods, and aesthetics of mainstream cinema and construct a counter-public discourse.

Synopsis: The heroic presentation of Dalit imagery, signifiers, gods, and belief systems is the fundamental characteristic of Mari’s style of filmmaking, and it is not an artistic limitation. In fact, these are counter-narratives against the epistemic violence in cultural representation created by the mainstream cinema for years.

Kaalamaadan is a cultural icon associated with the beliefs and traditions of Dalit socio-cultural life. However, the term Kaalamaadan, especially in the cultural sphere of Kerala, often refers to people who act in ways that disturb public conscience, challenge morality, or defy social conditioning.

Kaalamaadan has always carried a negative connotation and is used to blame or otherise people who adopt different perspectives or approaches in their thought processes or activities. This should also be understood as a historical continuity of caste practices to antagonise or defame the Dalit cultural symbols or icons.

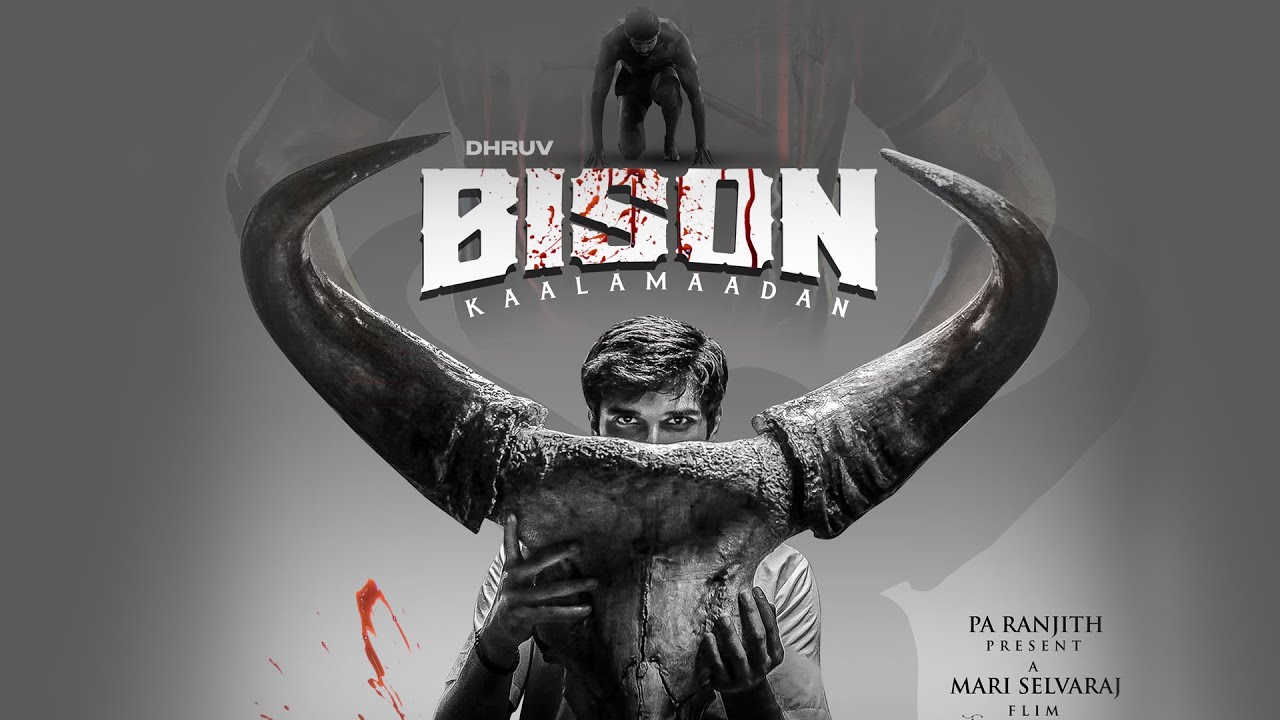

By naming the movie Bison, or otherwise known as Kaalamaadan, Mari Selvaraj is definitely dismantling the sarvarna gaze. Inspired by real-life incidents, the movie is set against the backdrop of socio-political happenings in southern Tamil Nadu during the 1990s. It discusses the survival, resilience, and triumph of Kittan, the Dalit protagonist.

The social history of Tamil Nadu is, in fact, a history of caste conflicts. Especially the southern districts of Tamil Nadu are infamous for their brutal violence against Dalits.

Kavin Selva Ganesh was murdered at Palayamkottai in Tirunelveli on 27 July.

The (dis)honour killing of a Dalit IT professional, Kavin Selva Ganesh, by the family of his girlfriend was one of the latest caste atrocity reported from southern Tamil Nadu.

The girl’s family hails from the dominant Maravar community, and both her parents are police inspectors. This reflects the current scenario of caste atrocities in southern Tamil Nadu, making the movie Bison more politically relevant. Though Bison doesn’t deal with the subject of honour killings, the film is presented in the larger context of the historical continuity of caste conflicts in Tamil Nadu.

The Pandiaraj-Kandasamy rivalry in the movie actually refers to the Dalit-Nadar conflict that happened in southern Tamil Nadu during the 1990s and early 2000s. The disputes, retaliations, and the feud between the Dalit leader Pasupathi Pandian and the Pannaiyar family have been effectively referenced in the movie. And this narrative has been successfully conveyed through the life and struggles of the Dalit protagonist, Kittan, inspired by the life of the Arjuna Award-winning Kabaddi player Manathi Ganeshan.

The film is structurally built on the notion of Dalit aesthetics and socio-cultural nuances. As many critics have observed, a specific pattern or preset template is being followed in Mari’s filmography. And the repetition of these patterns has invited criticism of Mari’s films, including Bison.

Mari Selvaraj

But what does this pattern really indicate? The heroic presentation of Dalit imagery, signifiers, gods, and belief systems is the fundamental characteristic of Mari’s style of filmmaking, and it is not an artistic limitation. In fact, these are counter-narratives against the epistemic violence in cultural representation created by the mainstream cinema for years.

The symbolic presentation of animals pertinent to Dalit social life, and their incorporation into the aesthetics of cinema, are essentially political acts. Even if it is repetitive in his filmography, it is a deliberative aesthetic of resistance and a new technique among the established imaginations of mainstream cinema.

Mari’s films, including Bison, subvert the established patterns, methods, and aesthetics of mainstream cinema and construct a counter-public discourse. It disturbs the public conscience, dominant perspectives, and morality constructed in films through different ages. So, the actual problem with critics is not the pattern of Mari but its content and politics. They are also triggered by the anti-caste politics occupying space in the public sphere through popular culture.

Recently, veteran director Adoor Gopalakrishnan has made casteist and gendered remarks against aspiring Dalit and women filmmakers, saying that they should be given ‘special’ training for filmmaking if they are receiving government funds for making movies.

Adoor Gopalakrishnan.

This thought, which shares concerns about the public fund when it is allocated to the marginal communities, is fundamentally a casteist idea. This also stems from the belief that filmmaking is meant for people from elite social backgrounds, as they are ‘naturally’ talented, while those outside this social structure lack the skills and ‘merit’ to create movies.

The criticism against Mari, based on the ‘patterns’ in his movies, also originates from a similar savarna gaze. Because

Mari has not just made some random movies, he directed films that deconstruct existing belief systems, culture, and politics, and he also made them commercially successful. Had his movies been a failure at the box office, none of the critics would have even cared about the pattern, content, or quality.

Therefore, the pattern he follows in his movies is successful in a political sense, as it disturbs the Gramscian idea of common sense.

The criticisms that have erupted recently are negating the identities of Mari, Vedan, Arivu, and Dhruv, who are integral parts of the movie, and revolve solely around the ‘fair’ skin of non-Dalit female actors. It seems that even the skin tones—or the absence of dark skin tones—of female actors in Mari’s movies disturb the public, as they do not meet casteist expectations.

Vedan at a concert in 2024. (Akshaysekhar/Creative Commons)

The idea of equating Dalits with dark bodies is actually a casteist notion. Why do people never question the non-Dalit filmmakers for not casting dark-toned and/or Dalit actors? Why is this burden solely placed on Dalit filmmakers? How can Dalit filmmakers who entered the industry after years of struggle be held accountable for the absence of Dalits and dark-toned artists?

These unfair criticisms emerge from a larger caste-ridden society. Furthermore, who decides that only Dalit actors should be portrayed as Dalit or characters with dark complexions?

But suppose the intention behind this question stems from a democratic concern about the absence of Dalits or Dalit women in cinema, why is this question being raised only against Dalit filmmakers? Why is there no question directed against the elite filmmakers who have been traditionally dominating the movie industry for years?

These controversies also imply that non-Dalit ‘fair’ actors have to be cast only in films directed by non-Dalits, which is again a sectarian casteist idea. Ultimately, when it comes to anti-caste cinema or Dalit subjectivity on screen, people still have a realistic/racist obsession for dark bodies, which arises from the stereotypes constructed by the public conscience.

Anupama Parameswaran.

There are also debates surrounding the toning down of characters played by Rajisha Vijayan and Anupama Parameswaran. In fact, enhancing or diminishing skin tone is a possibility in makeup, which is an integral part of any art form that involves acting/presenting.

Artists should use makeup as needed, depending on the character’s requirements. Using makeup is a common practice across art forms, including plays, dance, folk arts, and even Dalit art forms like Porattu Nadakam. But when it comes to cinema, people forget about the idea of acting, and the various tools involved in the process, including makeup, costumes, lighting, etc., that help to enhance or diminish the complexion, and express a realistic/racist obsession about the bodies of the actors.

This obsession also negates the possibility of Dalit and/or dark-toned actors playing any characters other than those consistent with their social/racial backgrounds.

However, the absence of Dalit/Dalit women actors in the film industry is obviously a serious concern and a political question for the larger film industry. Still it needs to be addressed differently, rather than through the ‘realistic’ obsession and the creation of an ethical crisis among Dalit filmmakers.

In India, the relationship between caste and colour is too complex a phenomenon to explain. It is impossible to address the larger political question of representation by simply comparing or equating both. Indians, as a community, actually have a range of skin tones from brown to dark.

A still from ‘Odiyan’ (2018).

These various shades of brown or dark cannot be identified as a marker of any particular caste. Presenting a character in any shade of brown or dark should be an absolute freedom for a filmmaker, based on the character’s requirements. However, it is essential to critically examine the stereotyping of a character within the context of the story.

For instance, the antagonist in the Malayalam movie, Odiyan, who hails from an upper-caste background, is portrayed as having an exceedingly dark complexion, which stereotypes people with dark skin. However, the case is entirely different in Bison.

For Mari, the characters played by Rajisha and Anupama, regardless of their social background or complexion, were appropriate tools to convey his larger political message. As some Dalit intellectuals have already observed, Dalit actors should have equal opportunity in the larger film industry and be cast as Vanniyars, Nairs, Brahmins, or characters

from any social background, irrespective of their complexion, using the possibilities of makeup and other techniques available in cinema.

This is what makes the movie more democratic and absolute as a modern art form rather than trapped in the caste-colour binary debates.

The history of Dalits’ engagement with film begins with PK Rosy, who was beaten up and forced to run away from Kerala by the caste Hindus as she played the character of a Nair woman.

PK Rosy.

And today, we live in an era where actors, regardless of their social background, eagerly await roles in movies by Dalit filmmakers such as Mari Selvaraj and Pa. Ranjith. Negating these historical and contemporary realities and confining the debate only to the ‘fair’ female leads in their movie is an elite conspiracy to subvert the political discourses constructed by Dalits.

Directors like Mari are actually challenging this kind of caste essentialism. As one of the characters says in the movie Bison, “No one will write your name in history, but you have to write your own,” and people like Mari Selvaraj and Pa. Ranjith are actualising this idea through their films.

(Views are personal. Edited by Majnu Babu).