Seven years after his demise on 27 September 2015, over 22 species of mangroves welcome you to Pokkudan's village in Kannur district. His family members now continue the mangrove propagation mission.

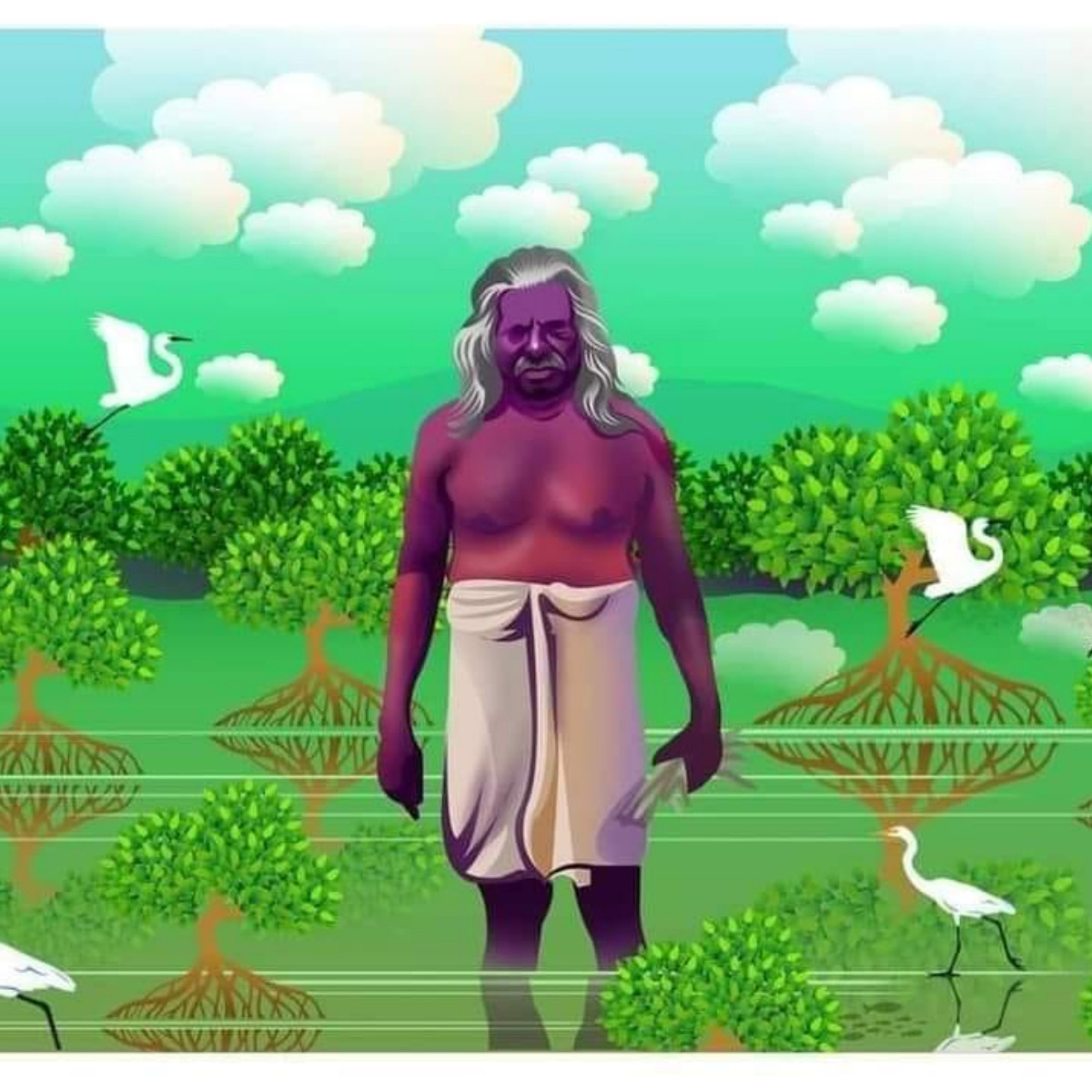

A portrait of Kallen Pokkudan by artist Dwijith (Supplied, with permission)

During his birth, Pokkan’s umbilical cord looked almost similar to the bloated and elongated seed of the common mangrove species that once thrived in his locality. So the neighbours affectionately tweaked his name to Pokkudan, which in Malayalam refers to infants with such umbilical cords.

That child with the bloated umbilical cord, born in the early 1930s to untouchable Pulaya parents in a northern Kerala village named Payangadi, later became the now legendary Kallen Pokkudan — a name that has over the years become synonymous with mangrove conservation, not only in India but all over the world.

Though sheer poverty and extreme caste discrimination prevented Pokkudan from going beyond elementary education, he carved a niche for himself in the world of conservation and coastal area protection. Pokkudan died on 27 September 2015, leaving behind a rich legacy of protecting over 22 rare species of mangroves in India from near total extinction.

According to Pokkudan’s elder son Anandan Paithalen, a conservationist in his own right, his father lived a simple life in close contact with the wetlands, backwaters, and coastal areas of the Kannur and Kasargod districts of Kerala.

Mangrove seedlings ready for planting in the Kannur coast under the initiative of the family trust of Kallen Pokkudan (Bhavapriya JU)

Pokkudan spent a significant part of his life on the collection, preservation, and plantation of the seeds of the once abundant long-fruited and stilted “mad mangrove” trees, known scientifically as Rhizophora mucronata.

Seven years after his demise on 27 September 2015, over 22 species of mangroves welcome you to Pokkudan’s village, which is nestled in the environmentally fragile wetlands of north Kerala’s Kannur district.

Till his death, this humble Dalit agricultural worker had planted over 3,50,000 mangrove saplings with his own hands not only in his native village but all over north Kerala.

Now his family trust is continuing the legacy by joining hands with the Kerala Forest Department to plant mangroves across the state’s coast to evolve a natural deterrent to continuing sea erosion.

His family recalls that Pokkudan started planting mangrove seeds in his native place in 1989 at 52. At that time, many people called him a crackpot.

Environmentalists of that time had little awareness about the role of mangrove forests in protecting the coastal ecosystem. When Pokkudan began his mission, the situation was that the mangrove forest area in Kerala had dropped from over 700 sq km to a paltry 17 sq km. The state has now achieved a considerable increase in the case of mangrove forests, thanks mainly to Pokkudan’s initiative. Because of his leading role, nearly 45 percent of the state’s remaining mangroves remain safe in his native Kannur.

Curiously, an acute political disillusionment led to Pokkudan’s passion for mangroves. The Dalit agricultural worker devoted most of his life to the organisational activities of CPI(M)’s agricultural labourers’ union. His long association with the party and its feeder organisations soured as soon as he started raising his voice against caste-based discrimination within the progressive party.

After leaving the CPI(M), Pokkudan was extremely depressed. He did nothing for almost a year. In those days, he saw little children getting drenched in monsoon storms while walking to school through narrow mud village paths via wetlands. The heavy winds used to take away their umbrellas, and storm waves regularly destroyed the embankments of the paddy fields.

Traditional knowledge helped Pokkudan realise that mangroves constitute the best buffers against the monsoon winds and the waves. But rapid urbanisation that swept the whole of Kerala had turned the mangrove forests into dumps for garbage from its numerous towns.

Urbanisation has severely affected the ecological functions of mangrove forests, such as nutrient cycling, flood control, groundwater recharge, salt dissipation, absorption and dilution of pollutants, and the creation of microclimatic niches that support a variety of life forms.

The deterioration of wetlands has pained Pokkudan immensely. For the untouchable Pulayas of Kerala, the mangrove forests always remained a significant source of food, fuel, fodder and medicine. These forests were a rich source of fish varieties that could be cooked or processed and kept apart for times of famine. Mangroves offered berries and tubers, which can be eaten either raw or cooked. Many of these mangrove forest products had high medicinal properties.

“My father used to tell us that the mangroves are known for their bounty, and most of the fish, the birds and the people depended on them,” says Paithalen. Pokkudan used to call the mangrove trees “the security guards of the earth”, and he was convinced that floods that cripple coastal regions would not kill so many people if there were mangroves.

For Pokkudan, collecting the seeds of the mangrove trees was not an easy task. In addition, the swamps were choked with waste. In the initial phase, the seedlings refused to take root because Pokkudan didn’t know the planting techniques well. But he started learning from his mistakes.

When the 300 seedlings he planted in his native village in 1988 started growing, Pokkudan’s efforts began to be noticed. Then the media, environmentalists, and forest officials arrived on the scene and started describing him as the guardian angel of mangrove protection.

In another three years, Pokkudan helped the forest department set up a mangrove nursery comprising 30,000 seedlings. He prompted local youth clubs to organise campaigns about the need to preserve mangrove forests. Civil society groups soon started putting up resistance against the destruction of the wetlands in the name of multi-crore developmental projects.

Throughout his existence, Kallen Pokkudan remained the last word on crucial swamp ecosystems. He maintained a proven ability to talk about the oppression faced by a Dalit in the same breath as the slow destruction of a coastal ecosystem.

He identified himself and those concerned with mangrove forests as part of the fragile coastal ecosystem.

“The birds roaming in the skies and nesting in the branches and tree heads of mangroves also have a right similar to all of us. As a Dalit, I had always ploughed the earth for others. Maybe that’s why I tried to explore the possibilities of protecting mangroves,” Pokkudan used to say.

Once, he said: “If anybody asks me how I wish to be identified in future, I would say Kandal Pokkudan (‘Mangrove’ Pokkudan)”.

May 12, 2024

May 08, 2024

May 08, 2024

May 08, 2024

May 07, 2024

May 06, 2024