Published Dec 16, 2024 | 9:00 AM ⚊ Updated Dec 18, 2024 | 11:53 AM

Dhoby Khana in Fort Kochi.

The silent murmur of a colonial past merges with the constant rumble of the Arabian Sea even as a breeze playfully ruffles the hair.

The edifices lining the streets with fading coats of paint spoke of a vibrant past of flourishing overseas trade and colonial forces shedding blood for supremacy. The streets of Fort Kochi in Kerala have many a tale to tell, most with the fragrance of spices that came down the mountains in the east.

The battle for supremacy brought the Dutch forces to Fort Kochi in 1663. They clashed with the Portuguese, took over the land and trade, and established their base in central Kerala, before moving southward almost a century later, only to be defeated by Marthanda Varma, the king of Travancore in 1741.

It marked the beginning of the fall of the Dutch. Soon after, the British vanquished them in Kochi in 1975, ending the Dutch dominance in Kerala.

The Dutch left, leaving behind their imprints cast in stone, and in the remains of hundreds of men, women, and children buried in the Dutch Cemetery in Fort Kochi.

A living memory from the Portuguese-Dutch era still exists in the shadows of Fort Kochi, a group of washermen community from Tamil Nadu who once kept the military uniforms neat and crisp.

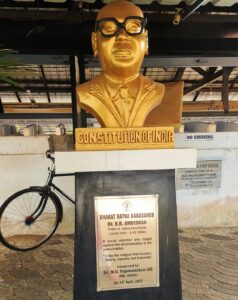

Dr Ambedkar’s bust at Dhoby Khana.

Down the Lavendria Road, a graffiti-adorned arch opens to Dhoby Khana Public Laundry, the remnants of a bygone era, are still full of life. A golden bust of Dr Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar stands beyond the arch, proclaiming freedom from a regressive past. “I like the religion that teaches liberty, equality, and fraternity,” the plaque proclaims.

Times have changed. But the lives of the washermen community, the Vannars, remain the same to an extent.

“En Vaanilae Orae Vennilaa,” the song from Rajinikanth’s 1980 movie Johnny drifts through the air, hinting at the Tamil connection of the community. Posters and paintings of Rajnikanth are everywhere, the actor keeps gazing in his vintage charm, far removed from his latter-day salt-and-pepper look.

Dhoby Khana, a hidden gem in Fort Kochi, is more than a Public laundry. It is a living tapestry of stories, from the Dutch era to the caste struggles and the fan culture of Rajinikanth.

Pratty has already sought Mariyamman’s blessings before starting her work.

“My day begins with a visit to the Mariyamman Kovil near this Dhoby Khana,” the 80-year-old woman with a warm smile at the vast ironing hall said. “You’ll find me here by 7 am. Till a few years ago, I used to arrive sharp at 5 am, but I can’t manage it anymore.” Age has caught up with Pratty.

Pratty with her late husband’s photograph. The photo, she said, was clicked by a ‘white man’.

Amidst the hum of activity, Pratty stands out as the only one still using the traditional coal ironing box, a method long abandoned by others in favour of electric irons. Despite her diminished eyesight and persistent aching arm, she continues to iron clothes with unmatched precision and care.

“I was born and brought up in Kochi. My grandparents migrated here from Tirunelveli. We belong to the Vannar caste.” she told South First.

Pratty is an uncommon name among South Indian women. She explained her name with a lively grin.

“In Kochi, you can find a variety of unique names, including mine, because of the influence of different cultures. But My name has no connection with the colonial era. ‘Pratty’ means ‘beautiful girl’ in ancient Tamil, a pet name you can find in the novel Ponniyin Selvan. My grandparents used to call me Pratty, and everyone called me by that name. My real name is Lakshmi,” she said.

The octogenarian said her ancestors were brought to Kochi by the king. “We Vannar’s were renowned for our expertise in washing clothes. In Kochi, our ancestors were assigned to wash the army uniforms of the Dutch, who were a prominent colonial power here at the time.”

The ‘Delhikkaran’

Pratty recalled her younger days. “There were no ironing halls or buildings for our work. We carried out our laundry tasks near the ponds in the area. At that time, our community-owned around 70 ponds spread across 13 acres,” she said.

In 1975, with the support of the Greater Cochin Development Authority, S Balakrishna Perumal established the ironing halls and other facilities.

“We fondly call him ‘Delhikkaran’ because he was then a prominent official in Delhi. He also introduced us to the teachings of Ambedkar Sahib,” Pratty explained.

The Dhoby Khana was established as compensation to the Vannar community for relinquishing 10 acres to create a public playground, now known as Veli Ground, as part of a city beautification project. In the past, the area had 70 ponds, but today, the community only has two wells as their source of water.

Rajasekharan is 62. He has been in Dhoby Khana for the past 47 years.

Rajasekharan at work.

“We were 300 families here, but now only 70 are in laundry services at Dhoby Khana. The younger generation prefers government and other jobs. Here in Kerala, we have reservations because we belong to the SC/ST community,” he told South First.

In Tamil Nadu, the Vannar community is listed as the Most Backward Caste (MBC), except in a few parts like Kanniyakumari and Sengottai.

“We earn according to the season. During the tourist season, we get bulk orders from travel agencies, homestays, and hotels. There are 435 homestays in this area, but only 10% give us work,” he added.

The dhobis earn between ₹500-1500 per day. “Everyone here is an expert in washing, boiling, and ironing. I use an electric iron box, which makes the job easier. However, older people still use coal iron boxes, which are expensive. We have to spend at least ₹3,000 on coal a month, and the heat is unbearable. It hurts the eyes,” he explained.

Selvi, along with her husband Babu, is active in the Dhoby Khana. However, she arrives only after sending her children to school.

Ground for drying clothes in Dhoby Khana.

“I am proud of this job. It’s better than seeking any other daily-wage work. This provides us with a steady, though minimal, income. There are nearly 40 laundry stones here, each assigned to a different person. We also have more than 20 dryers, which make the job much easier, especially during the rainy season,” she said.

The drainer, boiler, and other equipment were purchased by the Vannar Sangham, a cooperative society. “We contribute a small amount to the society for our welfare,” Selvi told South First.

Although the Dhoby Khana is a shared community space, each member has a designated area. Masani, 82, shared with South First,

“My ancestral home is in Thiruchendur, and I visit my relatives there every year. Each of us has a separate storage room here, with the key in our possession. We must ensure the clothes assigned to us are secure. After washing and drying, we keep the clothes safe in our designated space,” Masani, an 82-year-old woman, told South First.

Dhoby Khana is a favorite place for tourists and filmmakers. Tourist companies and travel agencies have close connections with the people here, and donations are officially made.

The entrance to the storage area.

Michael and Maria from Italy were at the Dhoby Khana for the second time. ”This is a very unique place that still follows traditional and ancient methods,” they told South First.

Films like Mumbai Police, Dheena, and Vikramadithyan were shot here in parts, adding to the rich cultural tapestry of this place. But perhaps the most fascinating aspect is the Dhobi Walas‘ deep love for Tamil cinema and music, especially their unwavering admiration for Rajinikanth.

A TV in the ironing hall constantly plays Tamil films, while Rajinikanth’s posters adorn the walls, creating an atmosphere where the passion for film stars runs through the veins of the community.

It’s a place that pulses with the energy of fandom and the festive spirit of Tamil culture.

Yet, beyond the rhythm of laundry and the movie magic, this place tells a deeper, more powerful story, one of the successors who were separated from their ancestral place and culture but who, through their hard work and resilience have built not just a life but an identity in the heart of Fort Kochi.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).