At a time when a woman was worth almost nothing, the plight of a widow was the equivalent of a burning hell. But Tirumalamba, as though she was not even touched by this heat, trod her own path with conviction all life long. Today is her 136th birth anniversary.

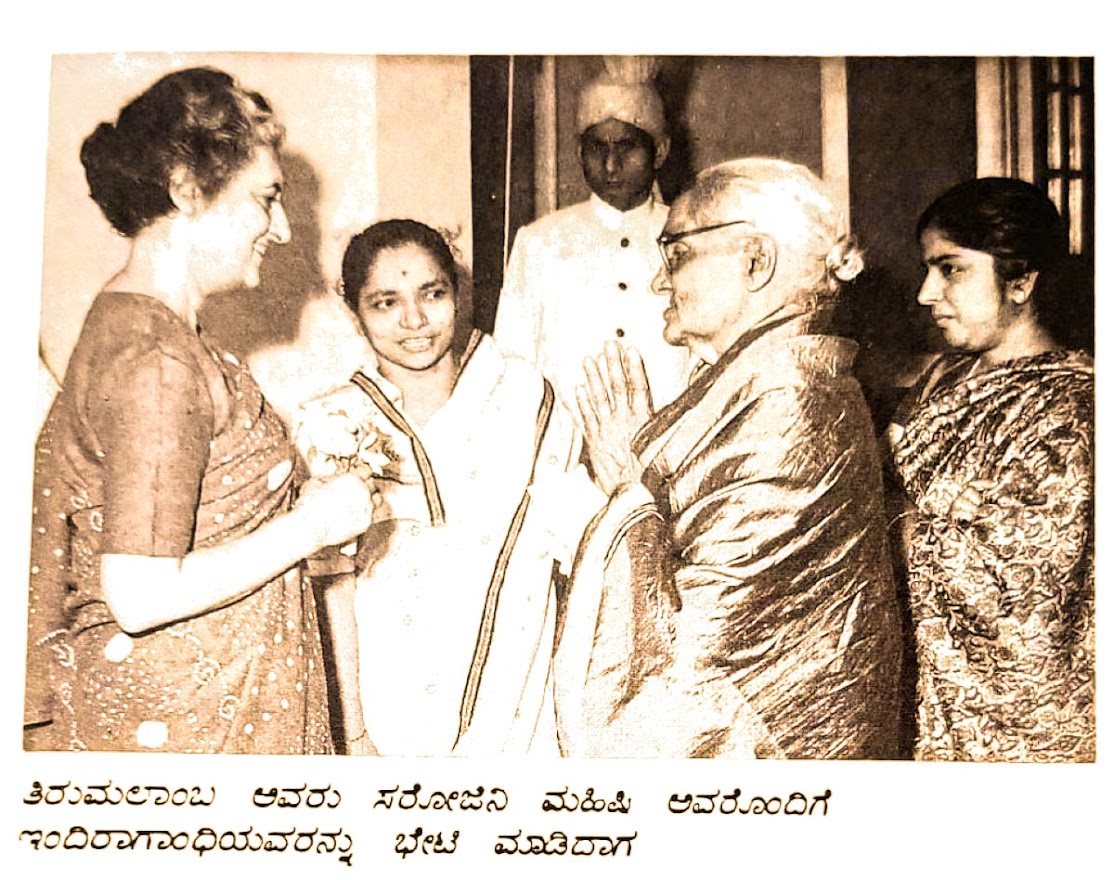

Nanjangud Tirumalamba, wearing spectacles, with the then prime minister Indira Gandhi. Between them is Sarojini Mahishi, another social reformer from Karnataka (MS Ashadevi)

A 15/16-year-old girl is staring right at the afternoon sun. She is of that delightful age when, having crossed her 14th year, she is ready to enter the bloom of youth and eager to fill it with all of life’s various colours.

But the patriarchal system had everything prepared to cut her life off before it even began. Married at 13, the girl had been widowed at 14.

With that, all the life left for her was so that she could “pestle parched rice”. It was in the darkness of such a future that the girl looked the brilliant sun full in the face.

Looking at the sun as though his radiance itself would light her path, the words “Mother Saraswati, it is you who must now show me the way” came to her lips of their own accord.

What happened after is both historical and contemporary. Historical because the fact that a woman reached the very pinnacle of success in her field over a century ago is a milestone; contemporary because the woman’s life, her personality, her writing were so unusual as to make one wonder, even today, if they were really of her time.

Nanjangud Tirumalamba (25 March 1887 — 1 September 1982) is a touchstone not simply in women’s literature in Kannada but in the entire narrative of the modern female experience.

In contemporary times, this narrative of the female experience is moving forwards in a decisive manner.

It is striving to create a hitherto untold historical narrative of the female experience. It is deeply concerned with constructing an entirely new historical map of human history.

A key objective of this construction is to establish that women’s struggle for self-determination and personhood is as old as human history itself.

Regardless of its nature, its dimensions, and its ups and downs, it has now been established that women’s struggle has been both relentless and unending. Tirumalamba’s achievements serve as an important illustration of this fact.

A page from Nanjangud Tirumalamba’s diary. She was an extremely disciplined and detailed diarist (MS Ashadevi)

The good fortune of a progressive father

Nanjangud Tirumalamba’s valour-filled life began on account of a movement for reform. Her father, who was involved in societal reform, did not allow his widowed daughter’s life to waste away.

He hoped education would help uplift a life that was slowly wasting away. In order that his daughter not lose her resolve or will, Tirumalamba’s father constantly urged her to keep up her studies and to keep the company of books.

In turn, not only did his daughter not let her life wither away, she came to think it was her duty to ensure other women’s lives did not wither away. In addition, she learnt that such devotion was capable of bringing both satisfaction and happiness.

Writing, publishing, editing, teaching, social work — Tirumalamba embraced and became part of society in a manner that knew no bounds.

This long journey of Nanjangud Tirumalamba ended up reaching such great heights that she even ended up meeting Indira Gandhi, the then prime minister of India.

That meeting was not on account of a wish for fame or for selfish reasons. It was because Tirumalamba believed that the participation of all women, no matter their status, was necessary for the grand goal of women’s upliftment.

In a letter people believe was meant to be sent to Indira Gandhi herself, Tirumalamba has written, “You are truly doing a good job because you are not limited by states and their boundaries; you are working for the betterment of all of your sisters.”

We talk these days about how “the strength of women lies in sisterhood”. It is important to note that not only did Tirumalamba foster such sisterhood, she also realised the strength it could provide.

At a time when a woman was worth almost nothing, the plight of a widow was the equivalent of a burning hell.

But Tirumalamba, as though she was not even touched by this heat, trod her own path with conviction all life long.

Even today, there are domains, including publication, that women are not allowed into. But in 1920 itself, Nanjangud Tirumalamba becomes a publisher and begins her own publication.

The cover page of a book brought out by Nanjangud Tirumalamba’s own publishing house. The book was part of a series titled Hitaishini (MS Ashadevi)

Despite her every effort, however, the newspaper fails. Finally, with the help of a 5,000 rupees grant for the Maharaja of Mysore, the publication takes off again.

Tirumalamba publishes a number of books in the series, Satihitaishini. Having understood through her own experience how important education is for a women if her position in society is to change, Tirumalamba takes up the cause of women’s education with a unparalleled fervour.

The Tirumalamba who was supposed to become the daughter-in-law of a wealthy Kollegala family goes on to become a prominent proponent of the truth that education and literature are the true wealth.

It was not out of necessity or helplessness or as a means to somehow lead her life that Tirumalamba used the tools of education and literature. Instead, Tirumalamba saw them as symbols of a woman’s personality, her self-respect and her personhood and looked at them with an awareness of how they could drastically change women’s place in society.

She thought constantly about the matter, wrote copiously about it, and was keenly involved in its implementation.

Tirumalamba’s innate discipline and the way she embraced and nourished her entire family speak to the immense forbearance she possessed.

The way she remained not simply unbowed in the face of numerous difficulties but also accepted and welcomed them only serves to increase our respect and affection for her.

Tirumalamba’s habit of noting not only the date a letter arrived, but the date she read it, and the date she responded to it testify to her being a woman of stern discipline.

The patriarchal society she lived in wished to see the widowed Tirumalamba as a dependent woman, who lived on others’ mercy and passed her life cursing her fate and indulging in self-pity.

Instead, Nanjangud Tirumalamba grew to be a woman who wished to consort with kings and queens and who shone while doing so. The Diwan of Mysore is said to have written to Tirumalamba, telling her how the Maharaja of Mysore read and was impressed by the series of books she brought out through her own publication.

It is only natural that the works of Tirumalamba, a woman who wished with all her heart for the liberation of women, are women-centred.

The conclusions and decisions she arrives at in her works often depress us and at other times inflame us. For instance, in her novel Sabha, the widow-protagonist rejects the idea of remarrying and decides to dedicate her life to serving society.

There may be several reasons why Nanjangud Tirumalamba had her heroine choose this path. It may be that she thought it was not a good idea for a woman who is only just beginning to start a new life to tread a path not accepted by society.

It may be that she thought that such a decision by a woman would increase men’s resistance to the idea of women empowerment and cause it to go backwards instead of forwards.

Or it might be that she truly believed that a life spent serving society was a fulfilling way to live one’s life. What makes it especially strange, though, is just how minutely and sensitively Tirumalamba describes the tragedies accompanying widowhood.

That the same Tirumalamba, who describes with great sadness the living corpse-like life a widow has to lead, makes her heroine take a decision to live life in a manner that is the opposite of the natural order of humankind is a matter of astonishment.

We must come to terms with this decision of Tirumalamba’s by telling ourselves that the pressure and awareness not to begin a revolution in haste were what led Tirumalamba to create such a heroine.

The world is used to describing a woman’s infinite capacity as a weakness. Tirumalamba was a woman-power who showed such a description was a sign not of a woman’s weakness but of the world’s weakness. My pranams to her.

(This article is a translation by Madhav Ajjampur of an essay by Dr MS Ashadevi. She is a leading Kannada critic who is well known for the feminist perspective she has used to examine Kannada literature. Her works include ‘Naduve Suliva Aatma’, ‘Naarikela’, and ‘Belakiginta Bellage Itta’.

Her areas of interest include literary criticism, comparative literature studies, and cultural criticism from a feminist perspective. Dr Ashadevi is the recipient of several awards, including the Prof MM Kalburgi Prashasti, the Infosys award, the Akka Prashasti, and the Nadaprabhu Kempegowda award. These are the personal views of the author.)

Jul 25, 2024

Jul 25, 2024

Jul 25, 2024

Jul 24, 2024

Jul 24, 2024

Jul 23, 2024