Ever since the Babri Masjid demolition on 6 December, 1992, the BJP has found a mass base among the Hindu voters there, with some exceptions.

Anti-incumbency has always been a strong factor in the Assembly elections in Karnataka. This is evident from the fact that for 40 years now, no government or ruling party has managed to get re-elected in the state — something psephologists call the “revolving door” trend.

This should naturally worry the ruling BJP, which is already facing serious corruption allegations.

In fact, these allegations have been converted into ammo by Opposition parties to brand the BJP government in Karnataka as the “40-percent commission government”, with whole campaigns built around it.

In this scenario, the Old Mysore region, where the BJP has historically registered its weakest performance, becomes crucial for the saffron party to buck this trend and overcome immediate anti-incumbency.

The region in question is nearly identical to what was once the princely state of Mysore.

The BJP became a force to reckon with ever since the demolition of the Babri Masjid on 6 December, 1992.

It found a mass base among Hindu voters across the country, except in the South and the Northeast.

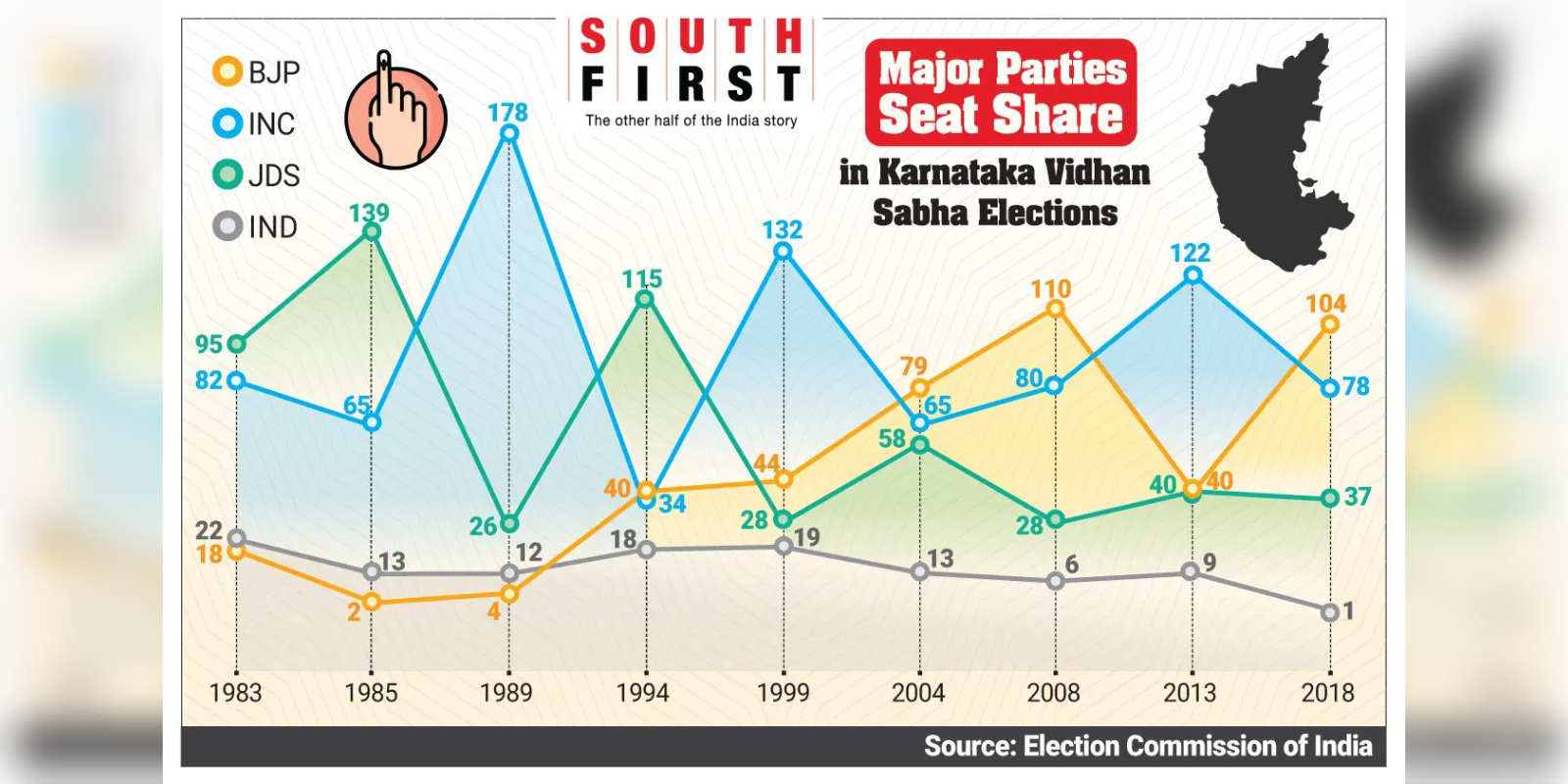

One exception in the south was Karnataka. In 1989, the BJP won only four seats and managed to garner 4.14 percent of the votes. But in 1994, the seat share shot up to 40 with an overall vote share of 17 percent.

The saffron party managed to emerge as the single-largest party for the first time in 2004, and went on to form the government twice, in 2008 and 2019, despite never breaching the halfway mark of 112 seats.

This tremendous growth in the BJP’s electoral fortunes was aided by the Lingayat vote bank, which is concentrated in Kittur and central Karnataka and smaller but influential pockets in the Old Mysore region and Kalyana Karnataka.

Religious polarisation helped the BJP make coastal Karnataka a stronghold for the party.

One region where the saffron party was — and still is — unable to make any inroads was the numerically strong and crucial region of Old Mysore.

The Old Mysore region (OMR), also called southern Karnataka, is dominated by the other dominant community — Vokkaligas.

The OMR, excluding Bengaluru Urban, comprises the districts of Bengaluru Rural, Ramanagara, Mandya, Mysuru, Chamarajanagara, Hassan, Tumakuru, Chikkaballapura, and Kolar.

It had 55 seats before the delimitation exercise in 2008 increased the segments to 59 in this region.

Traditionally, the Vokkaligas have largely supported the Janata Dal (Secular) or the JD(S).

Between the community’s two big subsects, the Gangatkar Vokkaligas in the Mysuru, Mandya, Ramanagara, and Hassan districts have been a dependable vote bank for JD(S)

Meanwhile, the Morasu Vokkaligas in the Bengaluru Rural, Kolar, and Chikkaballapura districts have traditionally favoured the Congress.

Ever since the BJP emerged as the single-largest party in 2004, the JD(S) has somewhat been restricted to just the OMR, except the single-digit seats in the Kalyana Karnataka region — the part of the state that was once ruled by the Nizams of Hyderabad.

This is evident from the fact that after 2004, the contribution of the votes for the party in this region compared to the overall votes polled for the party across Karnataka has improved in each subsequent election — from 41.7 percent in 2004 to 56.6 percent in 2018.

So far as the BJP is concerned, the post-Babri high contributed to the party winning eight seats in 1994 from the region out of the total 40 it won in the state.

The share of votes from the OMR in the total votes polled in the state for the saffron party was 21.5 percent.

In 1999, it managed to do much better by winning 13 seats from the region, with a regional share of 21.4 percent.

Nonetheless, these numbers do not tell the entire story. In these elections, the BJP was in an alliance with Ramakrishna Hegde’s breakaway faction — the Janata Dal (United) or the JD(U). It contested 149 seats.

In a post-Babri lull, it is safe to assume that vote transfer from the JD(U) to the BJP, especially in the OMR, helped the BJP improve its numbers seat-wise and maintain its vote share from 1994.

As the JD(U) weakened and paled in comparison to the JD(S), garnering only 2.1 percent vote share as opposed to the 13.5 percent vote share in 1999, the BJP’s performance in the OMR dipped in 2004, despite it emerging as the single-largest party in the state.

In 2008, the party slightly improved its performance in the region. The contribution of votes from OMR stood at 18.6 percent, an improvement of 4.2 percentage points.

One reason for this could be the “narrative of betrayal by the JD(S)” by HD Kumaraswamy floated by BS Yediyurappa and the BJP after he refused to give up the chief minister’s chair for the saffron party.

The party’s performance crashed, not just in the OMR but across the state, in 2013 when its tallest Lingayat leader BS Yediyurappa broke away to form his own party, the Karnataka Janata Paksha (KJP).

The saffron party managed to revive its electoral fortunes in 2018 when it emerged as the single-largest party.

Although the contribution of votes from the OMR was 5 percentage points less than the 18.6 percent it managed to garner in 2008, the party managed to win nine seats in the region.

It is clear from the above analysis that the OMR is somewhat of an Achilles heel for the BJP. Interestingly, even a marginal dispersed improvement had brought concentrated seats from this region. The saffron party seems to have already realised this.

On 1 March, BJP national president JP Nadda flagged off the first of the Vijay Sankalp Yatra from the Hanur Assembly constituency in the Chamarajanagar district in OMR.

It is important to note that the BJP won the Tiptur, Tumakuru City, Krishnaraja, and Chamaraja seats in both 2008 and 2018.

Moreover, even during its weakest performances in 2013, the party managed to win the Tumakuru Rural and Kolar Gold Field seats.

While the Congress made DK Shivakumar its state president to corner the Vokkaliga votes, the BJP has invoked “Vokkaliga pride”.

Sounding the poll bugle in December 2022, Union Home Minister Amit Shah exhorted Vokkaliga electorate to not “waste” their votes. “A vote for the JD(S) is a vote for the Congress,” he said in Mandya.

Furthermore, the BJP recently revealed a statue of Kempe Gowda, who is revered as the founder of Bengaluru and is an iconic figure within the Vokkaliga community.

Communal polarisation, which transformed the BJP into a mass party, is also part of the strategy.

The saffron party has been characterising Tipu Sultan, who ruled Mysore in the 18th century, as a religious fanatic.

Additionally, they are presenting Uri Gowda and Nanje Gowda, two purported Vokkaliga soldiers, as heroes who “killed Tipu Sultan”, a claim rubbished by historians.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi recently inaugurated the Bengaluru-Mysuru expressway and the BJP state unit has not lost the opportunity to campaign in the name of development. Ironically, it found itself in deep waters after the expressway flooded just two weeks after its inauguration.

With Mandya Member of Parliament Sumalatha Ambareesh, the influential actress and wife of popular film star-turned politician-Ambareesh, extending support to the BJP for the upcoming elections, it will be interesting to see how the saffron party performs in the Vokkaliga heartland of the OMR, which has always been a challenge for it.

Jul 27, 2024

Jul 26, 2024

Jul 26, 2024

Jul 26, 2024

Jul 26, 2024

Jul 26, 2024