Here is an interesting fact: No incumbent government or ruling party has got re-elected for almost 40 years now.

As we approach the 16th Karnataka Vidhan Sabha elections here is an interesting fact: No incumbent government/ruling party has got re-elected for almost 40 years now.

The last time this happened was when the Janata Party won the election in 1985.

In election studies, this phenomenon is sometimes called a “revolving door” and other times is called the “see-saw”. Whatever be the name, one obvious and general inference is that the average voter in Karnataka is highly sophisticated, discerning, and demanding.

But experts believe there are other specific factors for this phenomenon.

Rajasthan and Himachal Pradesh are two other prominent states in India with this revolving door phenomenon.

In the case of Rajasthan, it began in 1998 when the Congress’ Ashok Ghelot took over from the BJP’s Bhairon Singh Shekawat. Ever since, anti-incumbency has ensured no incumbent government could retain power.

Similarly, in Himachal Pradesh, the Congress’ Virbhadra Singh retained power in 1985. Ever since, the BJP and the INC have occupied the seat of power alternatively. Anti-incumbency played a strong factor here too.

In both the above states the contest has been primarily bi-polar. But in the case of Karnataka there is a difference.

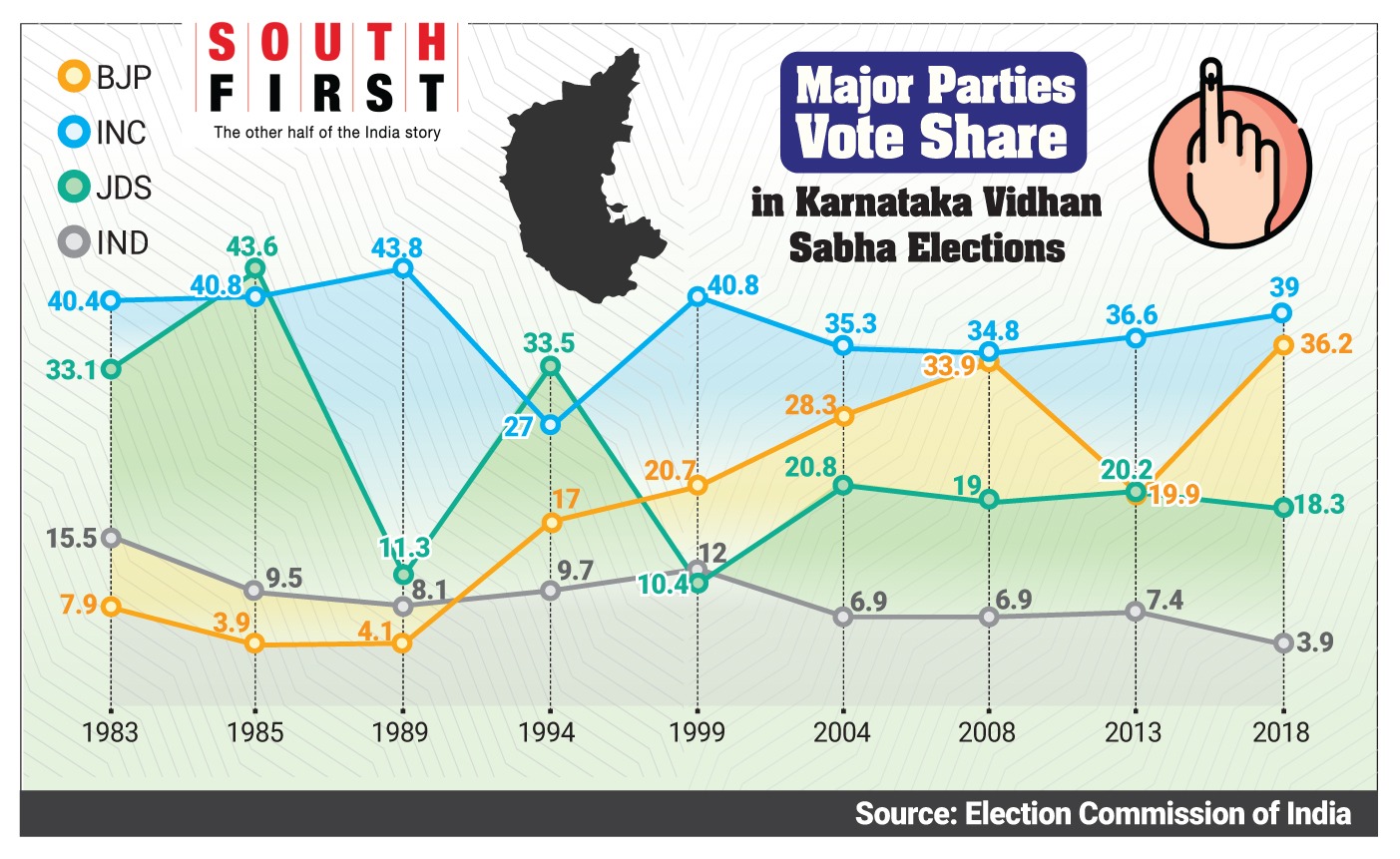

“Here, it is a tri-polar contestation. The INC, BJP, and JD(S) each win substantial vote shares and seats in each election ensuring that neither party wins a simple majority to form the government on its own,” Prof James Manor, Emeritus Professor, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, UK, and a long-time observer of elections in India told South First.

This phenomenon began in the aftermath of the Babri masjid demolition of the early 1990s.

“The BJP improved its seat tally from just four in 1989 to 40 in 1994. This, I think ushered in the three-way revolving door trend in Karnataka,” Prof Narender Pani of the National Institute of Advanced Studies told South First.

According to psephologist Prof Sandeep Shastri, Karnataka, for the longest time, had a leading Opposition and a distant Opposition.

“Two major transitions define Karnataka electoral politics. The first was in 1985, when the Janata Party retained power by breaking the Congress hegemony and ushered in a bi-polar contest. The second was in 2004 when the BJP broke through and replaced the JDS as the other main competitor to the INC,” Prof Shastri told South First.

In the first transition the Congress was the leading Opposition and the BJP the distant Opposition. In the second, the Congress became the leading Opposition while the JD(S) was the distant Opposition.

“The BJP could’ve managed a third transition in 2018, but it fell short. I think it was a missed opportunity. If they manage to win this time then the transition would be complete, with the JD(S) becoming a non-entity,” he added.

Karnataka elections are essentially bipolar contests in different regions.

“The BJP is dominant in the Kittur, Central and Coastal Karnataka regions, where it is in a bipolar fight with the Congress. The JD(S), on the other hand, is predominant in the Old Mysuru region and is in a two-way contest with the Congress,” Prof Pani said.

There are six political divisions in Karnataka — Bengaluru, Kittur Karnataka (previously called Bombay Karnataka), Central Karnataka, Coastal Karnataka, Kalyana Karnataka (previously called Hyderabad Karnataka) and Southern Karnataka or the Old Mysuru region.

The politically dominant castes, the Lingayats and Vokkaligas, are concentrated predominantly in the northern and central parts, and southern part of the state, respectively.

“The Veerashaiva movement occurred in the northern and central parts of Karnataka. And the Lingayats here are traditional BJP voters, helping the party win a substantial number of votes from constituencies in these regions,” Prof Manor said.

“The Vokkaligas are traditional supporters of the JD(S) and are concentrated in the Old Mysuru region. Therefore, Vokkaliga voters form the backbone of the JD(S),” he added.

Thanks to the efforts of Devaraj Urs, the Congress has traditionally banked on the AHINDA (Kannada acronym for Minorities + Backward Classes + Scheduled Castes) strategy. “The INC’s votes are distributed almost evenly and thinly across the state,” he further explained.

A direct consequence of this geographical distribution is that the BJP and JDS votes are highly concentrated, helping them win many more seats.

“In the first-past-post system, the more concentrated the votes of a political party the better vote share to seat share conversion takes place. For instance, in 2004 the Congress gained seven percent more votes than the BJP and yet the latter won 14 more seats than the former,” Prof Manor told the South First.

This is true even in subsequent elections when the Congress always polled more votes than the BJP.

In 2008, the Congress won 30 seats less than the BJP despite polling 0.7 percent more votes. Similarly, in 2018, INC polled 2.8 percent more votes than the BJP and yet won 26 less seats than the latter.

A clear reflection of the voter’s disaffection against the incumbent government is another crucial factor, according to Prof Sashtri.

“Since there are three alternatives, the choices available to the disaffected voter are more and it looks like voters in Karnataka are not afraid to exercise them,” he told South First.

Prof Pani has another interesting theory. “Due to successful decentralisation of politics, MLAs in Karnataka seem to enjoy more autonomy.

As the mood in the state shifts, these MLAs change loyalties too, which becomes an indicator for the voter to swing too.

“This, in conjunction with the volatility of the voter is, I think, one important factor for this revolving door trend,” he told South First.

Prof Shastri disagrees with Prof Pani, but only partially.

“MLA autonomy maybe not be entirely true. For instance, Operation Kamala, where 9-12 MLAs who shifted loyalties in 2019 to help the BJP form the government, had nothing to do with the charisma of the individual MLAs,” he pointed out.

Prof James Manor holds a more optimistic view. “Prof Pani comes up with very thought-provoking theories. It’ll be interesting to test this theory by looking at, say, the defections before the upcoming elections,” he said.