An excerpt from ‘The Pollen Waits on Tiptoe’, a book of the author's English translations of selected poems by DR Bendre, Kannada’s foremost lyric poet.

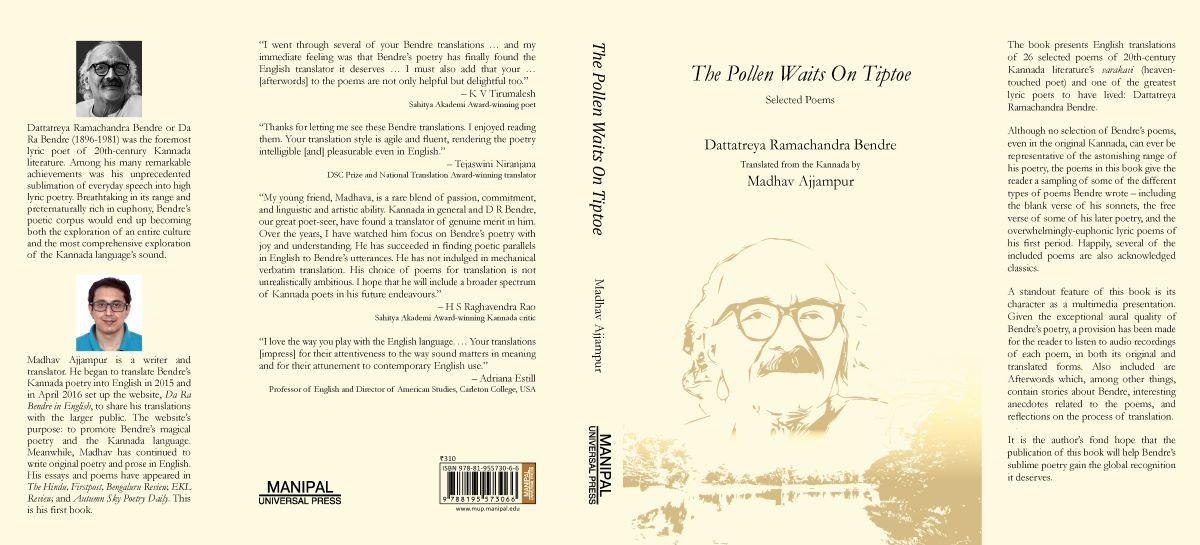

The back and front covers and the flaps of 'The Pollen Waits on Tiptoe', Madhav Ajjampur's English translations of selected poems by DR Bendre, Kannada’s foremost lyric poet (Supplied)

Though years and new years come and go,

New Year’s day is here again.

To the new year it’s bringing new cheer

and things that are newer and newer.

Within the shrubs of honge flowers

the bees begin their songs of play;

their symphonies are heard again.

The fragrance of the flower spills

upon the bitter tree of neem;

and look, the glow of life is seen.

Bewitched by Kaama’s fragrant shafts,

the mango tree has flowered forth;

it now waits eagerly for him.

And festooning the mango tree,

the parrots sing elatedly:

“the spring has come, the spring has come!”

The year itself’s been born anew;

the world’s joy has a resting place

within the hearts of all that move!

But in this single life of ours,

a single youth, a single prime;

is that all that we deserve?

A death with every sleep we sleep;

new life with every waking day;

why do we not have it so?

You god of youth-unending!

You wanderer untiring!

Does such a play not interest you?

Though years and new years come and go,

New Year’s day is here again.

To the new year it’s bringing new cheer,

and things that are newer and newer;

but not a single one’s for us!

According to the panchaanga (Hindu Lunar Calendar), Yugaadi (yuga + aadi ~ the first day of a new yuga) is the first day of chaitra maasa (the month of Chaitra), the first of the two months that make up the vasanta rutu (the spring season). Precisely, Yugaadi is the first day of spring.

Growing up, the only “New Year’s Day” I really knew was January 1. This was not because we did not celebrate Yugaadi (we did most years), but because Yugaadi was just one of the many celebrations that happened during the year. This made Yugaadi just another festival to be attended when it came around.

Another reason for my ignorance about Yugaadi was that it abided by the lunar calendar. This meant Yugaadi’s date changed every year, at least per the Gregorian calendar. New Year’s Day, on the other hand, never wavered: it always arrived on January 1. (That said, with a few exceptions, I do not have too many childhood memories of celebrating January 1, New Year’s day, either.)

For my traditional paternal grandmother, though, Yugaadi was the only new year there was. (It was only later, when she was in her 60s, or perhaps 70s, that she learnt of the “other” New Year’s Day of January 1.)

It was a day to be marked in the panchaanga and looked forward to; a day to celebrate the arrival of a new samvatsara (lunar year); a day to wake up early and wash and make the threshold sparkling clean, tie the tōraṇa (a string of tender mango leaves) outside the door, wash her hair, and wake up the children and get them ready; a day to make that famous metaphor, bēvu-bella (a mix of crushed neem leaves and jaggery, eaten together in recognition that life is both bitter and sweet); a day to use her renowned cooking skills to prepare those Yugaadi specials of huggi and obbaṭṭu and all those other festive foods that made Yugaadi such an anticipated celebration.

I mentioned my grandmother because she, like the poem, was of Bendre’s time — despite being about a generation-and-a-half younger than him.

But what do I mean when I say the poem was of Bendre’s time? Am I dating the poem and saying it is no longer relevant? Not at all. The poem is a song-poem for the ages. (Popularised throughout Karnataka when a portion from it was sung in a hit 1963 Kannada movie, it has become an anthem of sorts and an inseparable part of Karnataka’s Yugaadi celebrations.) It will, no matter what, remain in vogue as long as the festival does.

Instead, what I mean is that such a poem could not be written now. Written in 1932 CE (possibly to celebrate that year’s Yugaadi), the poem’s ingredients are of its time — a time when villages were still the heart of India; a time when festivals were not ostentatious extravaganzas but small community affairs; a time when most people did not know the date they were born on but, if they were lucky, knew the day according to the lunar calendar or in relation to some local event; a time when there was enough forest and nature around to see and listen to the buzzing of bumblebees and honeybees; a time prior to cut-throat globalisation, rampant urbanisation, and disastrous climate change; a time when neem and mango trees actually heralded Yugaadi by sending forth new leaves and blossoms in the chaitra month.

But despite all that has changed (for the worse and, in rare cases, for the better) since Bendre first wrote this poem, the questions he asks in it are eternal questions, made all the more relevant by the pandemic that saw hundreds of thousands of human beings die even as “[each] year itself [was] born anew” in the riot of flowers looking down from the Neem and Gulmohar and Jacaranda and Tabebuia trees.

Note: It is implicit in the write-up, but it is perhaps worth noting explicitly that the “New Year” and “New Year’s Day” mentioned in the poem are, respectively, the year (samvatsara) that begins with the arrival of vasanta (spring) and the first day of that year.

To listen to the Kannada and English versions of the above poem by DR Bendre, ‘New Year’s Day – Yugaadi’, click here. You can also scan the QR code above to get to the link.

[Excerpted with permission from ‘The Pollen Waits on Tiptoe’, Selected Poems of DR Bendre, Translated from the Kannada by Madhav Ajjampur, Manipal Universal Press (MUP)]

(Madhav is a writer and translator. He writes for several reasons, the most important perhaps being his wish to stay actively engaged with the world around him. His essays, poems, and translations have appeared or are forthcoming in several publications, including ‘The Hindu’, ‘EKL Review’, ‘Autumn Sky Poetry Daily’, ‘Another Chicago Magazine’, ‘Kyoto Journal’, and ‘Modern Poetry in Translation’)

Jul 25, 2024

Jul 25, 2024

Jul 25, 2024

Jul 24, 2024

Jul 24, 2024

Jul 23, 2024