Published Apr 15, 2025 | 5:02 PM ⚊ Updated Apr 15, 2025 | 5:02 PM

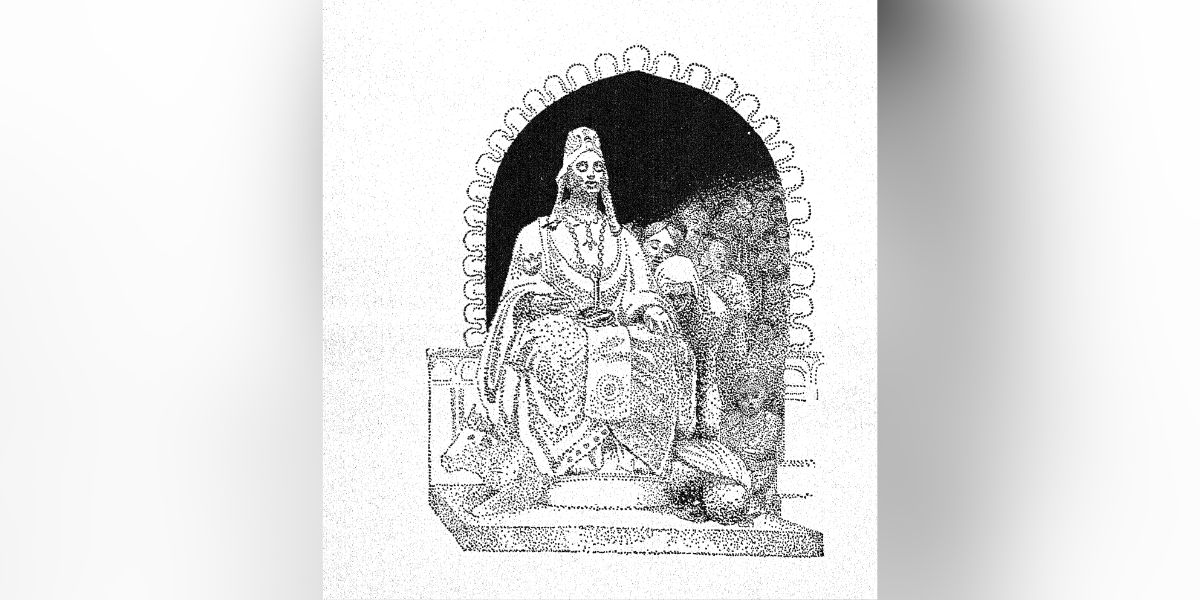

The Revolt of Sundaramma is not just about one woman as the protagonist. An illustration by Gertrude HB Hooker.

Synopsis: Maude Johnson Elmore’s “The Revolt of Sundaramma” depicts the story of a Hindu girl’s fight against child marriage, her struggle against slavery thrust upon her by society, and religion. Though set in the past, caste, and religion still hold sway in contemporary social life. Many old customs have either disappeared or transformed, but new superstitions and practices have replaced them — and those with sensitive, humanistic values cannot continue in such a system without rebelling at some point.

Losing my job after leading a strike in a failed-before-launch newspaper, and spending some months unemployed, I eventually got a placement in a prestigious research institute in Bangalore (the city was then still Bangalore) as a significant turning point in my life.

The change made a profound impression on me as the institute’s library, intellectual atmosphere, and friendships were great blessings. The library, in particular, was a treasure trove. Many books that I had only heard of but never had the chance to see became accessible to me.

With the availability of affordable photocopying facilities for students and staff at the institute, I was able to acquire books that I could not otherwise afford. One of the several valuable books I found there was The Revolt of Sundaramma.

Within two months of joining the institute, one of its employees and an acquaintance through common friends, suddenly asked me: “Do you know Sundaramma?”

I wondered who was Sundaramma. He was aghast that I, being a person with some literary credentials, was unaware of such a famous Telugu figure. “There’s a rare book called The Revolt of Sundaramma in our library. It’s a century-old book. You don’t know about her?” he was perplexed.

He then lent me the book, which was only allowed limited circulation at the time. It was three decades ago and I was deeply impressed with the book at that time, and even today, it has the same impact. This book vividly portrays the social life of Telugu society a century ago, and it holds considerable relevance even today.

The book mentions the names of three villages: Podili, Pedarikatla, and Rajupalem, the first two being villages in the present-day Prakasam district. It contains details of about 10 to 15 people, including their surnames.

The story of a woman who revolted against the inhumane practices of the Hindu caste system is depicted here. It’s a tale of a woman who, against her will, was married off to her maternal uncle at the age of four, became a second wife, gave birth to a daughter before turning 13, and then rebelled when she was about to marry her own daughter off at an early age.

The woman’s conversion to Christianity is presented as her act of rebellion. The readers may agree or disagree with the author’s interpretation of her religious conversion as a rebellion. However, of the book’s 16 chapters, only three or four chapters talk about Christianity. The rest focus on Hindu caste practices, the rituals created by Brahmins for their own benefits, and how a woman was oppressed and harassed under these practices.

The Revolt of Sundaramma is not just about one woman as the protagonist. The female author, Madge Johnson Elmore, dedicated the wonderful narrative about Sundaramma’s life to another woman, her mother, Rachel Poucher Johnson.

In the dedication note, she wrote:

“…whose constant devotion and rigid sense of duty caused me to enter many a Hindu home, unattractive at first sight, all as similar as peas in a pod, surprisingly clean, yet with the inmates living a life of dull monotony, bound hand-and-foot by sacred caste and strong religious customs, any efforts to change which seemed a hopeless work for a helpless people. But as the weeks and months and years swiftly passed, almost unconsciously to me, the loving, grateful, struggling Hindu people became my people, and it became my greatest joy to make known to them the Living God, the God of my mother”.

Thus, in the beginning of the book itself, she mentioned the caste and religious practices that made Indian society unattractive and monotonous, but ended the note with the love and gratitude of Hindus. Of course, she did not conceal her purpose of elevating her religious beliefs.

The illustrations in the book, done by another female Gertrude HB Hooker, are remarkable and full of life. The pencil or ink drawings show the life and labour of the people in great detail. Almost eighty sketches reveal the practices and professions of Telugu people, human beings, marriage customs, house structures, idols, dressing, cattle, fields, nature, birds, bullock carts, umbrellas, footwear, eateries, religious symbols and many more.

The introduction was written by Helen Barrett Montgomery, again a woman and one of the most renowned social workers in the USA during the early 20th century. Thus the book is entirely by and about women. The book was published in 1911 by Fleming H Revell Company, a Christian publishing house in New York, which had been active for 40 years and was one of the major Christian publishing companies in the Western world. It is now part of the Baker Publishing Group.

Why did an American author, illustrator, social worker, and publisher feel the need to write about a Telugu woman’s story? The author, Madge Johnson Elmore, came to the present Prakasam district (then part of the Guntur district) along with the American Baptist Mission, engaging in Christian missionary work, medical services, and possibly even conversion.

While the personal details of her life are not mentioned in the book, her son, Robert Hall Elmore, a renowned church musician, wrote in his biography that Madge and her husband, Dr Wilbur Theodore Elmore, lived in “Ramapatnam” (Ramayapatnam), and in 1913, a son was born to them. In 1915, the family moved back to the USA.

Madge, through her mission work, directly witnessed the suffering of the Hindu people, especially women, under the caste system, which led her to depict the life of a woman who broke free from these oppressive structures.

Whether this story is based on real-life events or a fictional account is uncertain. My attempts to verify the specific incidents in the villages mentioned did not yield results. I could not also find a detailed account of Christianity in this part of the country to check the veracity of the book. There was a small lead, in the surname Sundaramma shared with one C Jacob who was the Reverend at Ramapatnam Theological Seminary before he left for South Africa in 1910-11. But that lead could not be continued.

However, the internal evidence within the book strongly indicates that the author had substantial exposure to the Telugu society, customs, and Hindu religious texts of the time. Perhaps this is why many aspects of the book are still relevant today.

The story revolves around Sundaramma, a young girl married off to her 50-year-old maternal uncle, her struggles, her mother’s attempts to secretly marry her off, the birth of Sundaramma’s child at the age of 15, the death of her husband, and how she eventually left her home when her own daughter was about to be married off at a young age.

Sundaramma fled, seeking refuge with the missionaries, but due to the laws at the time, they were unable to take in her daughter. Eventually, Sundaramma’s daughter joined her, and Sundaramma found solace in Christianity. The book also talks about how she, along with other oppressed women and lower castes, sought a way out of their suffering.

While the book clearly discusses Brahmins and untouchable castes, the particular caste of the central character is not given and maybe from a middle caste. The story offers intricate details about the social, personal, and religious duties and responsibilities of people of the time, highlighting how caste, religious practices, and Brahminical dominance shaped people’s lives.

While many argue that modernisation has reduced the influence of these practices, caste and religion still hold significant sway in contemporary social life. Many old customs have either disappeared or transformed, but new superstitions and practices have emerged to take their place.

Hinduism, by its very scriptures, justifies inequality and use of force. Those who possess sensitive, humanistic values cannot continue within such a system without rebelling at some point of time.

The debate on conversion, in fact, should concentrate on this “push” factor rather than on the supposed “pull” factor of inducements and force, as is done elsewhere. This book, gives a lived experience of the role of “push” factor in conversion.

The book also invites reflection on the place of social reform literature in Telugu literature. It challenges the notion that literature created with a purpose lacks literary merit or does not faithfully depict life. The book shows that even literature created for limited and missionary purposes can be emotionally impactful and credible in its depiction of life.

After reading the book, I searched for reviews in the sociology journals available in the institute library from the 1910s, but I did not find any. However, reviews from The New York Times and New Zealand Herald that were published shortly after the book’s release are now available online. These reviews are thought-provoking.

As a portrayal of one woman’s life, as a declaration of the life of a Telugu woman by a foreign author, as a social science account, The Revolt of Sundaramma has gained even more significance today than it did when it was first published.

(The writer is the editor of an independent, small Telugu monthly journal of society and political economy, running for the past 23 years. Edited by Majnu Babu).