Published Sep 01, 2025 | 5:19 PM ⚊ Updated Sep 01, 2025 | 5:19 PM

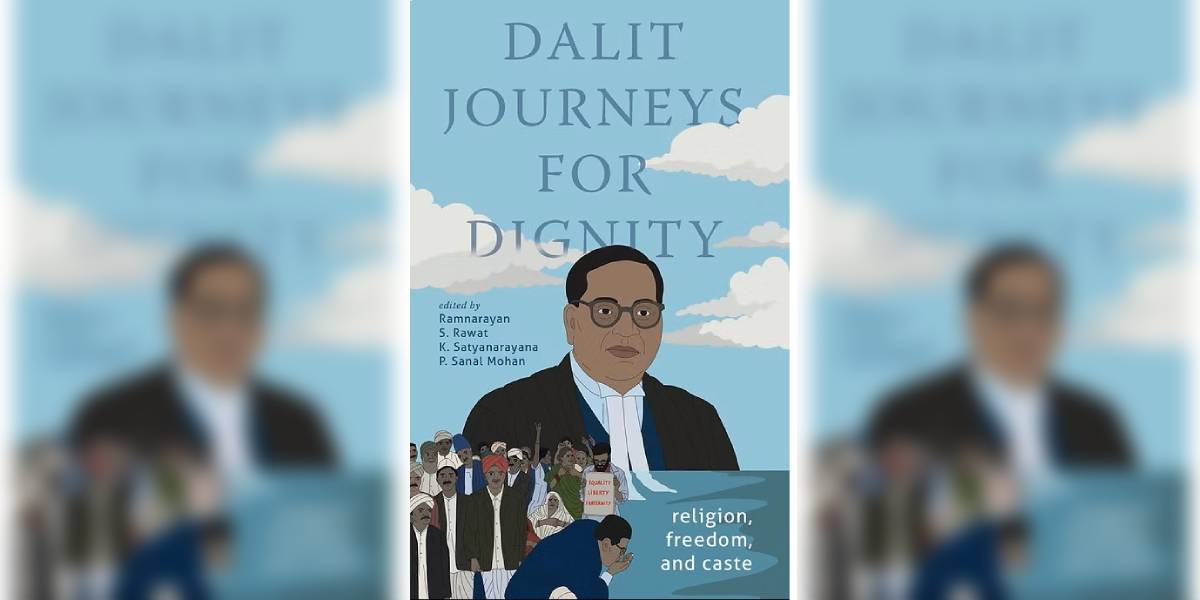

'Dalit Journeys for Dignity: Religion, Freedom, and Caste' is not just an edited collection; it is a declaration of purpose.

Synopsis: Dalit consciousness, especially since the 1980s and 1990s, has reshaped Indian politics, literature, and social science. The rise of Dalit autobiographies, literature in regional languages, and militant groups like the Dalit Panthers forced society to confront what caste oppression meant in everyday life. Dalit voices, long silenced, began to speak for themselves. This was not simply a cultural assertion; it was a demand for recognition and equality.

Rohith Vemula’s parting words continue to reverberate in the mind as a painful reminder of the failures within Indian democracy. His note was more than a farewell—it was a powerful critique of a society that stripped him of dignity, even in a university that professed ideals of equality.

His death became a rallying cry, stirring protests that revealed how deeply caste continues to structure India’s institutions of higher learning. Vemula stood as a symbol of an unfinished struggle – one that generations of Dalits have carried forward through movements, writings, and acts of defiance.

His story reminds us that Dalit struggles are not matters of history but urgent realities, played out in classrooms, hostels, and everyday life.

It is to this unending demand for dignity that Dalit Journeys for Dignity: Religion, Freedom, and Caste speaks. Dedicated to Vemula, the volume insists that Dalit Studies function not just as an academic field but as a deeply political and moral commitment to confronting injustice.

Rohith Vemula.

Dalit consciousness, especially since the 1980s and 1990s, has reshaped Indian politics, literature, and social science. The rise of Dalit autobiographies, literature in regional languages, and militant groups like the Dalit Panthers forced society to confront what caste oppression meant in everyday life. Dalit voices, long silenced, began to speak for themselves. This was not simply a cultural assertion; it was a demand for recognition and equality.

In academic terms, this period also saw the emergence of Dalit Studies as a distinct field. It must be placed against the backdrop of the fading of Subaltern Studies.

Launched in the early 1980s by Ranajit Guha, the Subaltern Collective had attempted to recover histories of peasants, tribals, and workers. For over two decades, it challenged elite and nationalist histories. However, its limitations became clear by the 1990s. Its focus on agrarian revolts and colonial archives, its drift into abstract theory, and its neglect of caste and gender made it increasingly distant from social struggles. The project ended in 2005, leaving a vacuum.

Dalit Studies filled that space but with a radical shift. Drawing from Ambedkar and Phule rather than Gramsci, it placed caste, untouchability, and dignity at the centre. It treated autobiographies, oral histories, and community memories as archives.

More importantly, it was not just descriptive but normative: it sought to dismantle caste oppression and affirm Dalit subjectivity. In doing so, Dalit Studies democratised knowledge itself, opening Indian social sciences to voices and methods long excluded.

The first volume of Dalit Studies (2016) established the field, historicising Dalit politics and thought. But it is the second volume, Dalit Journeys for Dignity (2025), edited by Ramnarayan S. Rawat, K. Satyanarayana, and P. Sanal Mohan, that gives sharper direction to the project by making dignity its central theme.

The editors’ introduction draws on Ambedkar’s concepts of “the social” and “moral stamina.”

Ambedkar had argued that political democracy—elections, constitutions, parliaments—was meaningless without social democracy rooted in equality, fraternity, and justice. Dignity, therefore, was not an ornament but a foundation.

Ambedkar’s insistence on embedding the phrase “fraternity assuring the dignity of the individual” in the Constitution’s Preamble emphasised his belief that political democracy must be grounded in social equality.

For the editors, dignity is not imported from Western rights discourse but arises from Dalit histories of humiliation, resistance, and refusal. They emphasise Ambedkar’s notion of inner resilience—what he referred to as ‘moral stamina’—as essential for enduring systemic humiliation and waging sustained resistance.

The essays in this volume, drawn from the International Dalit Studies Conference, expand these ideas across religion, freedom, and caste.

Several essays focus on the ways Dalits used religion to escape the prison of caste and reclaim dignity.

Chakali Chandra Sekhar tells the story of Nanchari, a Dalit in nineteenth-century Andhra Pradesh, who defied temple bans, rejected caste labour, and embraced Christianity not as submission but as resistance. His act sparked collective conversions and challenged Brahminical dominance.

Ramnarayan Rawat links Ambedkar’s vision of fraternity with the Sant tradition of Kabir and Ravidas. These movements, rooted in equality, provided a cultural grammar for Dalit assertion.

Koonal Duggal analyses the Ravidassia movement in Punjab, showing how martyrdom after the killing of Sant Ramanand in 2009 became a source of religious and political dignity.

Equally compelling is Jestin T. Varghese’s essay on Dalit Christianity in Kerala. Missions opened schools and literacy, but preserved segregation. Dalits were baptised yet denied burial rights or leadership in church life. From these contradictions emerged a distinct Dalit Christian identity, one that reinterpreted faith on their own terms.

The essays also broaden Dalit Studies into new terrains. Lucinda Ramberg highlights how caste and sexuality are intertwined. Caste sustains itself by policing women’s bodies and enforcing endogamy. Ambedkar’s call to abolish caste, she notes, meant also dismantling this sexual order.

Inter-caste marriage and Dalit women’s assertion of agency are thus central to dignity. Anupama’s essay on sartorial dignity shows how clothing became a means of challenging caste hierarchies. From Ambedkar’s advice that Dalit women dress well to the adoption of uniforms, ornaments, and Western attire, clothes became statements of self-respect and mobility.

Sharika Thiranagama examines inheritance and kinship in Kerala. Despite land reforms and literacy, Dalits remain excluded from property transmission, exposing the myth of Kerala’s egalitarianism. Dignity, she argues, requires dismantling these hidden but powerful mechanisms of caste continuity.

Sumeet Mhaskar turns to industry, showing how modern factories reproduce caste hierarchies.

Dalits are concentrated in insecure and hazardous jobs, while supervisory roles remain closed. He calls this “immobility within mobility”—better wages without real equality.

Finally, Dickens Leonard, in a hermeneutical mode, reconstructs Iyothee Thass’s reinterpretation of Tamil history. By linking Dalits to early Buddhism, Thass reclaimed a dignified lineage that resisted Brahminical dominance. His intellectual project prefigured Ambedkar’s own turn to Buddhism and illustrated how history itself can become a tool of emancipation.

The volume’s strength lies in inputting Ambedkar’s insights into diverse contexts—religion, sexuality, inheritance, labour, and history—while keeping dignity as the unifying theme. It expands the archive of Dalit Studies beyond state documents to include oral histories, cultural practices, and everyday struggles. It also democratises scholarship by focusing on Dalit voices rather than elite interpretations.

Dalit Journeys for Dignity: Religion, Freedom, and Caste is not just an edited collection; it is a declaration of purpose. By dedicating the volume to Rohith Vemula, the editors remind us that the struggle for dignity is not an academic abstraction but an urgent, lived reality. The book positions Dalit Studies as the rightful successor to, and radical departure from, Subaltern Studies.

It insists that democracy without dignity is meaningless and that social sciences must be democratised by including those voices long excluded.

For students of caste, religion, politics, and history, this volume is an essential read. More importantly, for anyone concerned about the future of Indian democracy, it offers a simple but profound truth – the struggle for dignity is not behind us, but it is the horizon we must still reach.

(The author is the Director, Inter University Centre for Social Science Research, Mahatma Gandhi University, who earlier served as Senior Professor of International Relations and Dean of Social Sciences. Views are personal. Edited by Majnu Babu).