Published Aug 06, 2023 | 8:56 PM ⚊ Updated Aug 07, 2023 | 6:40 PM

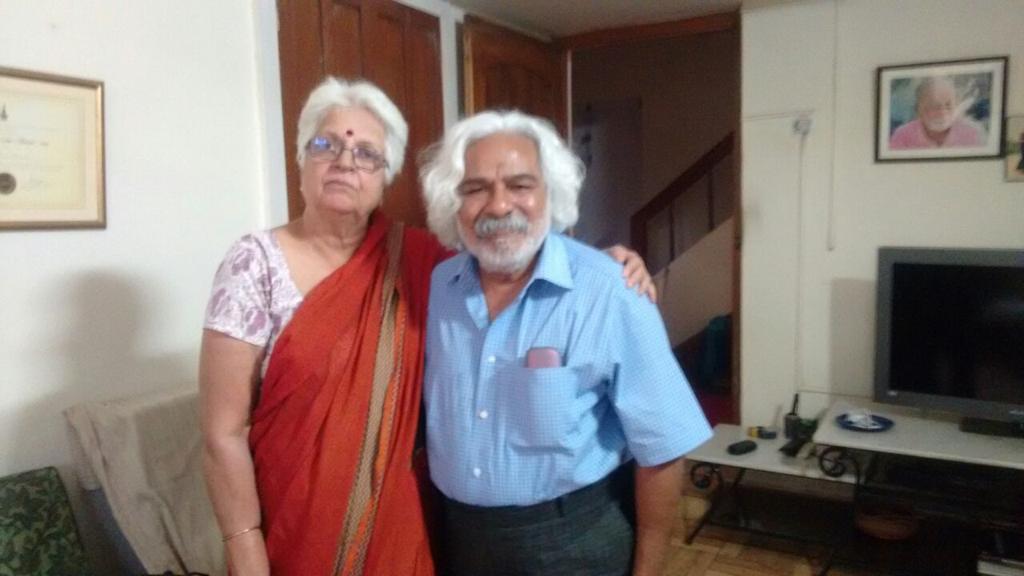

File photo of Vasant Kannabiran with Gaddar. (Supplied)

(Preface to ‘Gaddar, My Life is a Song: Anthems for the Revolution’, translated by Vasanth Kannabiran. Speaking Tiger Books, 2021)

Venturing into the task of translating Gaddar was both quixotic and suicidal. I had asked for one poem of his to include in an anthology of Telugu writing that I was translating. Having struggled with a range of genres spanning a century this didn’t seem to be difficult. It was only when I picked it up his voice, his eyes, his gongadi and the dappu all appeared vividly before me looking at me quizzically. Taking a deep breath, I picked up one of my favourites and struggled to capture the voice and the emotion to my satisfaction. He had left a whole file of poems with me for me to choose. After a few months I wondered and asked him whether he wanted me to translate them. He was overjoyed. And my sorrows began.

I have known Gaddar since the Emergency. He has been a constant presence along with several brilliant revolutionary writers and poets who were all instrumental in shaping my political consciousness and widening my intellectual horizons. Gaddar has been moving around with a bullet lodged near his spine for the last twenty years. He is diabetic, exhausted, and in pain. That bullet is my personal bond with Gaddar. On 1 April 1997 when we had just heard that student leader Chandrashekhar had been shot dead while speaking in Siwan, Bihar and were sitting in shock, plainclothes policemen stormed into our house herding two busloads of “naxalite victims” to protest to Kannabiran about his human rights defence of naxalites and the consequent damage to poor people like them. The police intention was clearly to jostle and knock down Kannabiran in a stampede. There were families of men who had been killed or mutilated by naxalites for becoming informers. However, once they were with him, the fact that the people saw him as a saviour and began to appeal to him for justice thwarted that attempt. The next target was Gaddar who was not at home that day. Two men, generally believed to be plainclothes police, returned to his house a few days later and shot him at point blank range. He was rushed in a critical state to Gandhi Hospital. Huge crowds were milling around the hospital afraid that the police would enter to complete the unfinished task. The air was electric with anger and tension. The police and the doctors allowed me to enter and see him, because they recognised me. The crowd kept urging me not to leave his side. Kannabiran was in Karimnagar on a fact-finding mission. The doctors told me that he was critical and needed to be shifted urgently to the Nizam’s Institute of Medical Sciences (NIMS) for surgery. Every minute was critical. The crowd outside would not allow him to be moved and blocked the gates fearing that the police would take him away and finish him off. I had to go out yelling and convince the tense, disturbed crowd to let the ambulance go if they wanted him to survive. They parted and allowed it go insisting that I stay near him. We followed the ambulance. The doctors at NIMS were waiting and the surgery began as soon as he reached. Fortunately he survived. They removed three bullets but one bullet was too near the spine to be touched. With characteristic irony the State provided him with security guards after the event. Twenty years later he still moves around with a security guard and a bullet lodged safely in his back. The police sketch based on Vimala’s description of the man who shot Gaddar was the image of the man who was next to Kannabiran a couple of days earlier jostling him very roughly. I went into shock on seeing that sketch.

None of our neighbours, all good people and true, heard or saw anything that night or asked us what the commotion was about. This was on a plane that neither concerned nor bothered them.

In a deeply depressing context ridden by corrupted controversy and criticism the value of a bard like Gaddar who sings truth to power is inexpressible.

I had watched so many of his performances, witnessed his expression, the rise and fall of his voice, the pauses, the bursts of passionate drumbeats, the moving lyrics, the adoration of his spellbound audience and the power and passion that he poured into describing the death of countless youth, comforting bereaved parents, inspiring more youth to pour into a struggle which meant certain death and unimaginable torture. I felt that I should translate him risking criticism and rebuke. I went ahead stubbornly thinking that something was better than nothing.

Coming to the text, while the lyrics are woven by Gaddar, the performance itself is something that is shaped and fuelled by the passion, hopes, fears and needs of his audience. The manner in which the adoration of his audience and their need for a reflection of their lives pushed the actual performance to unbelievable heights needs to be experienced to be understood. To capture that in cold print is not possible. And yet the words have a beauty of their own. They are poignant, triumphant and elegiac transporting the listener while straddling immeasurable grief, joy and hope. They draw on the common everyday songs and lyrics of the people of this region, songs for festivals, dirges for funerals, common songs danced to as part of daily life now transformed to assure people that the slaughter of so many young lives and futures is not completely in vain. That there is hope and liberation in the future. He is both a beacon of hope and a legend. And that quality is impossible to capture. To grasp the pain and passion interlaced in his words one need to step away from Anglophone assumptions and strive to walk in the slush.

I believe that however inadequate my effort his voice and his words must be made available in some degree to readers in other languages. That his voice must be preserved for posterity. A translation that could help non-Telugu readers to appreciate the scope of his performance if they are ever fortunate enough to see him perform.

Politics, political affiliations, and internecine disagreements apart, he is the bard of the Naxalite movement, of the People’s War Group and represented its essence at the height of its glory in his work. He sang of the movement and its martyrs, of its goals and aspirations to the people it addressed in the language and local idiom of the people. Kondapalli Koteswaramma (the erstwhile partner of the People’s War leader, Kondapalli Seetharamaiah) once made a perceptive and critical remark. She said that the political classes taken by the Communist Party in early days was like feeding a child avakai on its annaprasan [hot mango pickle at the first ceremonial feeding of rice]. She also said that the facts flung at them were like boiled gram hard as iron pellets [inapaguggillu] difficult to swallow or digest — a quality common to leaders trapped in slogans and political jargon beyond the reach of the people they sought to liberate. [Source: Stree Shakti Sanghatana, We were making history: Women in the Telangana armed uprising, New Delhi: Kali for Women, 1989.]

Gaddar however sings and dances, the songs telling of poverty, exploitation, struggle and martyrdom in an idiom rooted in the soil to people drawing them closer into the fold of the movement. And not all the criticism or controversy that surrounds a political figure of that stature can diminish the greatness of his art.

The fact remains that he is beloved by the people. However tired or gray or hoarse he grows, he has only to pick up his blanket and his staff and he is transformed into this towering legend adored by the people. A man of the people — larger than life speaking of the joys and sorrows of ordinary mortals, their hopes and fears, their hungers and pains, their heartbreak. And that voice, which is the voice of the people of Telangana, makes him one of the most relevant writers of his time. His work is something that needs to be preserved, enjoyed, treasured and disseminated to the greatest extent. It is the heritage engraving their culture.