Published Sep 06, 2025 | 11:00 AM ⚊ Updated Sep 06, 2025 | 11:00 AM

Revanth is looking beyond simply auditing past irregularities, but he is also attempting to erase KCR’s most visible imprint on Telangana’s landscape — Kaleshwaram — and replace it with an alternative irrigation vision rooted in Congress’s own legacy.

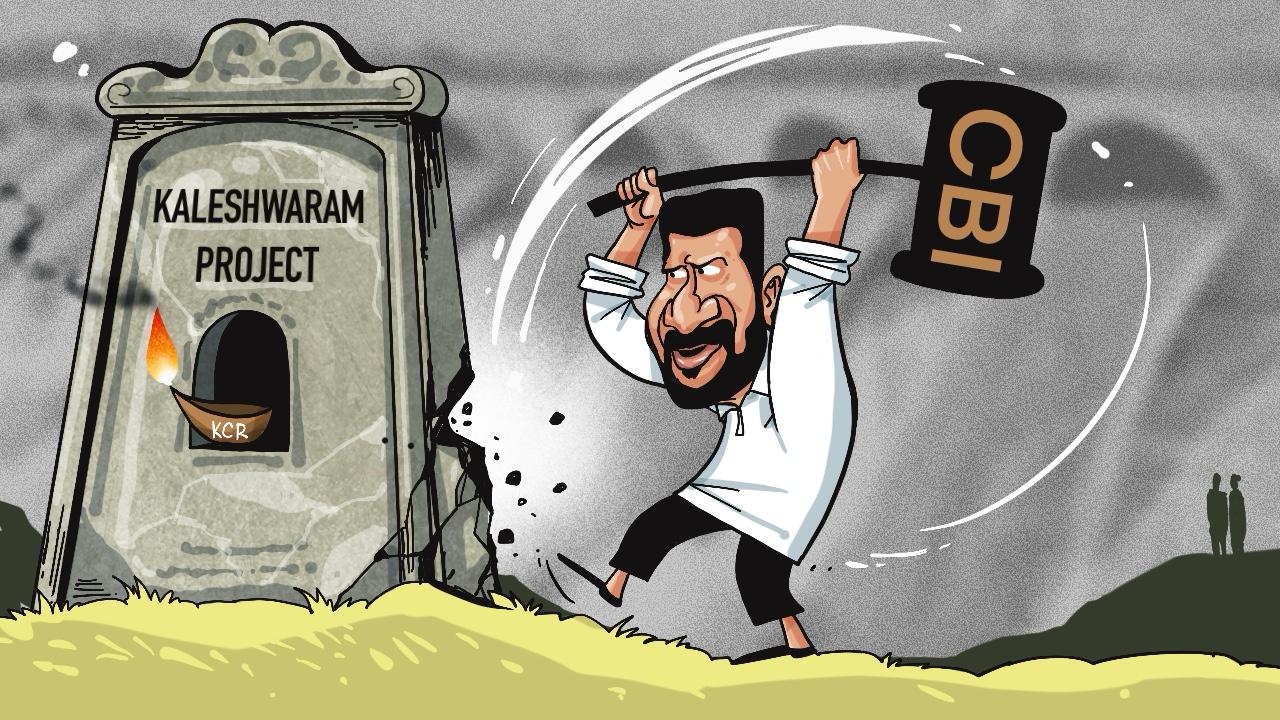

Synopsis: Telangana Chief Minister A Revanth Reddy seems to be on a mission to dismantle the legacy of his predecessor, K Chandrashekar. However, his efforts to revive the Pranahita-Chevella project, and paint the Kaleshwaram Lift Irrigation Project as a ‘monument of corruption’, may backfire if the CBI could not pin any blame on KCR, and Pranahita-Chevella project turns out to be not feasible.

Telangana Chief Minister A Revanth Reddy appears to have set in motion a political strategy to dismantle the carefully cultivated legacy of his predecessor, K Chandrashekar Rao.

His first task was to target the Kaleshwaram Lift Irrigation Project (KLIP) with which KCR has been associated. He ordered a CBI investigation into the ₹1.20 lakh crore project, which he calls a glaring symbol of corruption of monumental proportions.

In a parallel development, the Congress government is trying to resurrect the long-forgotten Pranahita-Chevella project. It signals a pivot in the state’s irrigation priorities that could redefine Telangana’s political and development narrative.

Together, these moves suggest that Revanth is looking beyond simply auditing past irregularities, but he is also attempting to erase KCR’s most visible imprint on Telangana’s landscape — Kaleshwaram — and replace it with an alternative irrigation vision rooted in Congress’s own legacy.

“Come what may, I will revive the project. It was the vision of Rajasekhar Reddy,” Revanth said at the YSR Memorial Awards function on Tuesday, 2 September.

When KCR inaugurated the Kaleshwaram project in 2019 with much fanfare, it was billed as an engineering marvel. Spread across multiple barrages—Medigadda, Annaram, Sundilla, and others- it was designed to irrigate 18.25 lakh acres of fresh ayacut and stabilise 18.82 lakh acres of existing ayacut across Telangana. The BRS projected Kaleshwaram as the “Lifeline of Telangana,” equating it to the pride of the newly carved out state.

However, within just a few years, cracks — both literal and metaphorical — emerged. Structural damages to the Medigadda barrage, rising maintenance costs, and allegations of inflated contracts and substandard works are perceived to have eroded the project’s reputation. The Justice Pinaki Chandra Ghose Commission’s observations on possible irregularities in awarding contracts provided additional ammunition to the Congress government.

Revanth’s decision to refer the Kaleshwaram case to the CBI marks the sharpest attack yet on KCR’s credibility. It puts the former chief minister, his close associates, and contractors under the national scanner, making it difficult for the BRS to defend the project without appearing complicit.

KCR’s daughter, K Kavitha, has already set off a firestorm, saying that the BRS leaders, mainly former irrigation minister T Harish Rao, had a large share of the spoils from the project. For Revanth, the probe serves a dual purpose: Exposing corruption and undermining the very foundation of KCR’s claim to have transformed Telangana into a land of “milk and honey” through irrigation.

Political symbolism

Beyond accountability, the move has deep political symbolism. Kaleshwaram was marketed as the BRS government’s flagship achievement and was closely tied to KCR’s persona. By dismantling its credibility through a corruption narrative, Revanth aims to demolish what the KCR’s critics call — the mythology built around him as the “Architect of Telangana’s Water Revolution.”

The Congress leadership seems to believe this approach could resonate with farmers and rural voters, who are disillusioned by the lack of Congress-promised benefits. Many farmers complain that the water supply has been erratic, and promised crop yields remain unrealised. By tying these grievances to corruption, Revanth positions the Congress as as the saviour and messiah, willing to clean up the mess and deliver real solutions.

The Congress also seems to believe that the CBI probe distances the state government from accusations of political vendetta. By involving a central agency, Revanth tried put on a show that he favoured transparency and harboured no intention of wreaking vendetta against KCR.

He also sought to ensure that the investigation garners national attention — an important factor in discrediting the BRS beyond Telangana’s borders. When the CBI finally begins the investigation, it would likely be continue for a long time and in the meantime, the general elections, which are more than three years away, would have arrived. This way, the Congress intends to keep the issue alive and inflict a death by thousand cuts on KCR’s legacy.

Even as Kaleshwaram is pushed into controversy, the Congress is quietly bringing the Pranahita-Chevella project back into the conversation. First conceived under the late YS Rajasekhara Reddy government in undivided Andhra Pradesh, the project aimed at utilising water from the point where Pranahita tributary joins Godavari at Thummidi Hatti to irrigate drought-prone areas in Telangana.

After statehood, KCR shelved it, arguing that much of the ayacut fell in Maharashtra and that water-sharing disputes made it unviable. This apart, water availability is less at Thummidi Hatti in Adilabad where Pranaja Chevella project begins with a reservoir. Instead, he promoted Kaleshwaram as the alternative.

Revanth’s renewed thrust on Pranahita-Chevella carries layered political intent. It revives a Congress-era vision, thus reclaiming credit for irrigation planning in Telangana. It also signals that the government is not merely engaged in tearing down BRS projects but is committed to offering alternatives.

The ruling party believes that fresh negotiations with Maharashtra could make Pranahita feasible. If successfully revived, it could provide irrigation to districts like Adilabad, Medak, Nalgonda, Nizamabad, Warangal, Karimnagar, and Ranga Reddy.

One of the most debated questions in political circles is whether Revanth’s strategy signals a complete abandonment of Kaleshwaram. Officially, the Congress government has said it will not let public money go waste and will attempt to salvage usable parts of the project. But the political narrative on the project indicates otherwise.

By painting Kaleshwaram as a “monument of corruption,” the government is delegitimising it beyond repair. By pivoting to Pranahita, Revanth Reddy is trying to appear investing in a project untainted by scandal.

However, abandoning Kaleshwaram entirely carries risks. The scale of funds already pumped into the project makes it difficult to justify walking away from it, and farmers who have benefited— even partially — may resist its neglect. Revanth will therefore have to strike a balance: Using the corruption narrative to weaken KCR politically while ensuring that essential components of the project continue to serve farmers.

The battle between Kaleshwaram and Pranahita-Chevella is not just about dams and canals—it is about political ownership of Telangana’s irrigation agenda. For KCR, Kaleshwaram was both a development project and a political brand. For Revanth, dismantling it and promoting Pranahita is about reclaiming that space.

By turning Kaleshwaram into a symbol of corruption, Congress hopes to permanently dent BRS’s image, especially among rural voters. By reviving Pranahita-Chevella, Congress can project itself as the party delivering sustainable irrigation answers, thereby building long-term political capital. This way the Congress hopes to undo KCR’s narrative of being the sole architect of the state’s development. By challenging the legacy project of the BRS —Kaleshwaram— the party aims to rewrite Telangana’s story with Congress at its center.

But Revanth’s new strategy is a high-risk, high-reward political maneuver. If the CBI probe uncovers major irregularities, it could devastate the BRS’s credibility and permanently tarnish KCR’s image. If Pranahita-Chevella is successfully revived, it could cement Congress as the party that delivers genuine irrigation benefits.

However, failure on either front could backfire. If the CBI probe stalls or yields little evidence, Congress risks being accused of political theatrics. If Pranahita proves technically or politically unviable, the government may be seen as sacrificing the interests of farmers.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).