Published Jul 18, 2024 | 5:56 PM ⚊ Updated Jul 18, 2024 | 6:28 PM

Some 100 kilometres away from Hyderabad, EMRS Kalwakurthy is also facing many challenges, thanks to the recruitment of teachers from Hindi-speaking states.

South First brings to you a series of ground reports from across Southern states on the impact of Union government’s decision to impose proficiency in Hindi as a mandatory yardstick for teachers’ recruitment to Eklavya schools. These schools are meant to focus on education for children from tribal communities. The language barrier is stressing parents and students. Worse, Union government’s move is rendering native teachers jobless. This ground report from Telangana is the first part in the series.

The queue was grim, long, and winding. Two sets of people have queued up outside the EMRS Society in Hyderabad’s Nampally early on Monday, 15 July.

Their gazes were fixed ahead though a few glanced furtively at the surroundings. Many of them were new appointees to Eklavya Model Residential Schools (EMRS), seeking a transfer out of Telangana; others were seeking re-employment after they had been replaced with fresh recruits.

The Eklavya schools are part of the Union Ministry of Tribal Affairs’ flagship programme but are run by the state government.

Deputy Secretary V Chandra Shekhar looked helpless even as more people joined the queue. “When the Centre proposed centralising the teacher recruitment process, we were upbeat. We thought it would bring better teachers,” he said.

However, his belief went wrong as the Union government took over the whole process, ending a Centre-state collaboration that have been on since the inception of the schools in 1997-98.

The Union government had allocated ₹6,399 crore for the EMRS programme in its interim Budget for the financial year 2024-25, up 150 percent from ₹2,471.81 crore for the year 2023-24 set aside in the previous fiscal. The earmarked amount consumed most of the ₹13,000 crore budget of the Ministry of Tribal Affairs.

However, as of June 2023, the Union Ministry of Tribal Affairs formed the National Education Society for Tribal Students (NEST) to manage the 690 schools across India.

Of the total schools, 23 are in Telangana, at least on paper. As of 2020 only 16 of these schools are functional. According to the Telangana EMRS Society, it employs over 1,090 staff members to manage over 8,244 students.

“Currently, the Centre is responsible for everything, from notifying vacancies to placement. The state is responsible only for paper evaluation and candidate verification,” Chandra Shekhar said, adding that there were inefficiencies in the new system.

“Nobody is better aware of Telangana’s needs than those who have run the schools all this while. When the Centre takes over placements, it disrupts the balance in sensitive areas,” he stated.

Earlier, the EMRS staff were outsourced locally on a contract basis. With the new system, candidates must now pass three rounds of evaluation: A preliminary paper, a main paper, and an interview.

While the evaluation pattern seemed standard for a government job, making Hindi proficiency a mandatory criterion to pass has raised many concerns.

Apart from English, the medium of instruction, and the subject the candidate was to teach, each applicant has been mandated to have a degree of proficiency in Hindi, regardless of their state of domicile, or where they would be posted. Competence in Hindi has become a mandatory yardstick since 2023.

The decision has resulted in a disproportionate number of recruits from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Haryana, cutting short the strength of non-Hindi-speaking teachers. Reports of teachers switching to Hindi mid-lecture further added to the concerns of parents, and students.

At Balanagar EMRS, B Prem Sagar Naik is among the 32 new hires replacing the previous teachers.

The 25-year-old man belongs to the local Lambadi community. He admitted that making Hindi mandatory has disadvantaged a major chunk of the aspirants.

“The centralised recruitment process is undoubtedly beneficial to students. However, the flaws in the exam pattern have caused a disproportionate hiring of staff, both in terms of language and gender,” he stated.

The school, set up in 1997-98, was among the pilot batches of the EMRS programme. Being a child of two teachers, Sagar hoped that the students would have local teachers, relatable and accessible.

“It is the first-generation learners that face the challenge the most. Their parents are quite sceptical of the sudden change,” Manju Oommen, the school’s principal, said.

She observed that the similarities between Lambadi, the native tongue of the predominant ST community, and Hindi were similar, aiding the students.

Sugandha Gangwar, a native of Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh, a new teacher, said that it was just a matter of time before things settled down, noting that English was bridging the gaps between the students and teachers.

However, Oommen suggested that the incoming staff undergo sensitivity training to facilitate a well-rounded approach to educating a critical population.

“EMRS has the potential to emulate Navodaya. It means that these students will get better opportunities and more exposure. It’ll even allow them to compete at the national level,” she opined.

Yet, Oommen said that a fresh start would have been a better approach to implementing the change rather than a complete overhaul, rendering many jobless.

Chandra Shekhar echoed the same sentiment, predicting that it could have significantly improved the quality of education. “Despite its benefits, the painful reality [sic] remains that over 500 previously outsourced employees lost their jobs overnight,” he acknowledged.

He stated that about 480 personnel have been appointed based solely on merit. He noted that while there was an evident language barrier owing to most recruits being from the Hindi heartland, most parents responded positively, anticipating better education services.

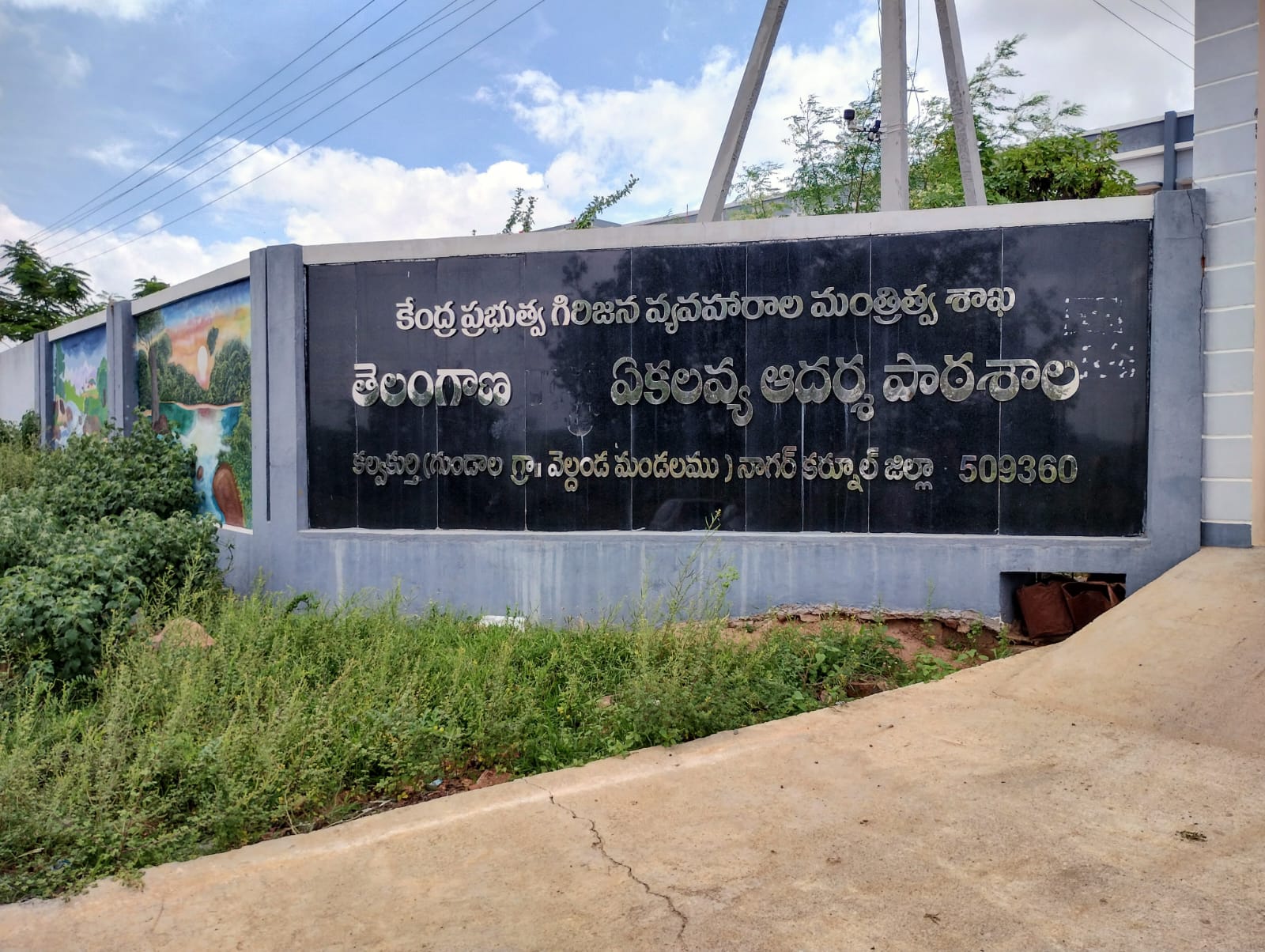

Some 100 kilometres from Hyderabad, EMRS Kalwakurthy in the Nagarkurnool District, too, faces challenges similar to its Balanagar counterpart.

Set up in 2017-18 the school is relatively new. N Saraswathi, the Principal, resonated with the general opinion that the Centre’s initiative was well-intentioned, but riddled with challenges.

“When explaining complex lessons, the teachers could switch to Telugu to make the students understand better. However, with the new staff, the children will lose this opportunity,” she noted.

Saraswathi is a part of the outsourced employees who retained her position, besides eight other faculty members.

“Most of the new hires are young with barely any experience. It will be a definite challenge for them to establish a bond with the students who are used to the previous Telugu-speaking staff,” she said.

She further stated that it would be time for the school to function at its best again.

Reena, a newly appointed Computer Science teacher lauded the move as beneficial to the students. “The children here are hard-working like their peers elsewhere in the country. They deserve empowerment to move beyond the confines of the state. They need to know that there is a world beyond their home and it’s theirs,” she said.

A resident of Haryana with 15 years of teaching experience, she admitted that there would be challenges. Reena added that she would put in all efforts to help the students’ growth.

“To tackle the linguistic challenges, we suggest that teachers develop their English communication skills. It doesn’t matter where a teacher is from, or their qualifications. They will succeed if they can impact a child,” Venkat Narayana, the Vice Principal of EMRS Kalwakurthy said.

Narayana, with 25 years of teaching experience, said the school was lucky to retain part of the earlier staff making the transition easier.

Many candidates hailing from the Hindi heartland have requested transfers, some even foregoing the job.

The increasing demand for transfers resulted in a notification asking candidates not to approach any NESTS Centre with transfer requests until a transfer policy is in place.

Gope Ravi, a Botany teacher at EMRS Kalwakurthy, expressed concern over the lack of transparency in the exams for recruiting new teachers.

“Emulating the Navodaya schools is not the right move for EMRS. Navodaya has a mixed student population. EMRS primarily deals with children from ST communities. They require special attention and a more accessible staff to help them grow optimally,” a teacher, who wished to remain anonymous, said.

N Nagesh, a Biology teacher, felt it unfair to force Hindi on a Telugu-speaking state while the reverse remained unacceptable. He added that the government should have recruited locally instead of recruiting people from another state.

In May 2024, the unemployed teachers took the issue to court. “I have filed two writ petitions representing over 100 teachers in the state. The imposition of Hindi has virtually ousted over 50 percent of India’s population from the job,” Srikanth Chinthala, an advocate at the High Court, noted.

He questioned the necessity to make Hindi mandatory when most teachers do not teach the subject. He felt the decision was irrational.

“Alienating students from ST communities that are mostly unaware of Hindi could have alarming consequences. It undermines the purpose of the EMRS programme. Not only is it against the spirit of federalism, but also disrupts the linguistic harmony in society,” he stated.

Interestingly, the schools are named after the mythological character Ekalavya, the Nishada archer mentioned in the Mahabharata. Nishadas, according to experts, spoke the Munda languages.

(Edited by Majnu Babu)

(South First is now on WhatsApp and Telegram)