Published Jan 18, 2025 | 1:00 PM ⚊ Updated Jan 21, 2025 | 10:00 AM

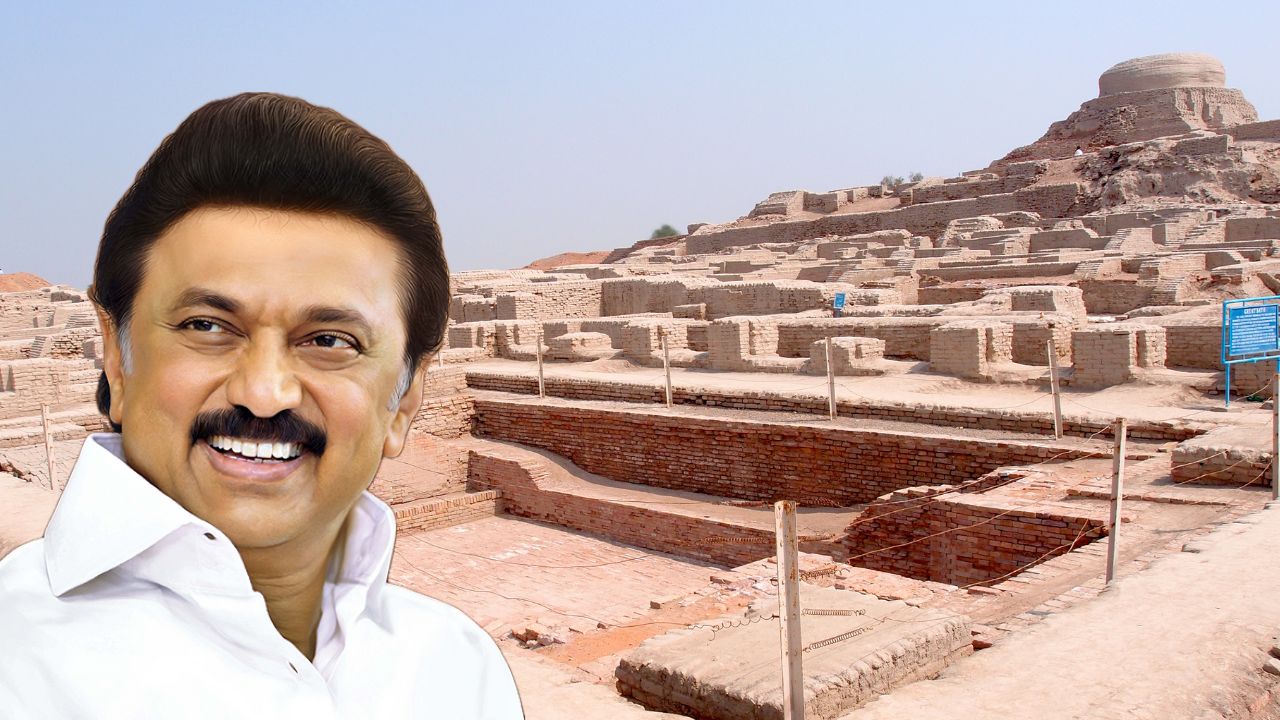

Stalin announced a $1 million reward for deciphering the Indus Valley script.

Earlier this month, Tamil Nadu Chief Minister MK Stalin announced a staggering $1 million prize money for experts or organisations that can successfully decipher what he called “a century-old mystery.”

The announcement came during his address to historians, archaeologists, and academics at a three-day International conference at the Government Museum Auditorium in Egmore. For those familiar with Dravidian politics, the subject of this mystery might come as a surprise: the Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC).

The Dravidian Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) leader’s focus on what many consider an “Aryan civilisation” or a predecessor to Vedic north Indian culture seemed unexpected, but Stalin had an explanation:

“Many used to argue that it was a figment of imagination that Aryan and Sanskrit were the origin of India. John Marshall’s discovery completely changed the perception. His argument that Indus Valley Civilisation predated Aryan Civilisation and the language spoken in the Indus Valley could be Dravidian has been strengthened further,” Stalin told the gathering, which marked 100 years since the IVC’s discovery.

During the event, he also laid the foundation stone for a statue of Sir John Hubert Marshall, the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) Director-General who first announced the discovery in 1924.

“We are not able to decipher the script of the Indus Valley Civilisation that flourished once. It remains a mystery even after 100 years,” Stalin continued.

“Archaeologists, Tamil computer experts and linguists across the world have been making efforts to decipher the script. To encourage the research, the government will offer one million dollars.”

Beyond the prize money, Stalin announced a ₹2-crore grant to establish a chair in honour of renowned archaeologist and epigraphist Iravatham Mahadevan. This position will facilitate joint research on the Indus Valley Civilisation between the State Department of Archaeology and the Indus Research Centre at Chennai’s Roja Muthiah Library.

The chief minister also unveiled a new book, Indus Valley Scripts and Tamil Nadu Symbols: A Morphological Study, whilst emphasising Tamil Nadu’s “deep cultural ties to the Indus Valley” through shared artefacts, symbols, and burial practices.

The Indus Valley Civilisation was one of the world’s earliest urban cultures, flourishing alongside ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia during the Bronze Age from approximately 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE.

At its peak, this remarkable civilisation covered around 1.25 million square kilometres, extending from Afghanistan in the west to the Gangetic plains in the east and reaching as far south as present-day Gujarat.

The IVC stands out for its advanced urban planning, with archaeological evidence pointing to a notably peaceful society. Despite extensive research, the Indus script – discovered on seals, pottery, and other artefacts – remains undeciphered even a century after its discovery, leaving the language and much of the administrative and social structures unknown.

For the DMK government, these efforts in research are not merely about solving an ancient puzzle. They aim to establish a direct link between modern Tamil culture and one of the world’s oldest civilisations, potentially rewriting the narrative of Indian history in the process.

Archaeological remains and artifacts considered to be of Sangam Age – at ASI’s Keeladi Excavation Camp near Madurai in Tamil Nadu. (Wikimedia Commons)

The state government is exploring connections through excavations at Keeladi in the Madurai district. These excavations have drawn comparisons to the Indus Valley Civilisation due to the discovery of artefacts dating back to the Sangam period (300 BCE to 300 CE).

These include pottery, graffiti, and beads, which historians argue are similar in design and function to items excavated in Harappa and Mohenjo-daro.

Dilshad Fatima, a senior research fellow at the Department of Ancient History, Culture, and Archaeology at the University of Allahabad, who attended the conference, told South First: “While the timeline differs, the spirit of innovation and trade seen in Keeladi and the Indus Valley resonates with what we know about the Cholas. However, it’s vital that we separate fact from conjecture and ensure that our historical narratives are rooted in evidence.”

IVC Terracotta boat in the shape of a bull, and female figurines. (c. 2800–2600 BC). Wikimedia Commons

Fathima further emphasised that preserving the individuality of a culture is essential, as each culture embodies unique traditions, values, and expressions that define its identity. “

“While it is important to recognise connections, overemphasising these links can dilute the distinctive essence of a particular culture,” she said.

“By focusing too much on aligning culture with broader frameworks, we risk overlooking its unique spirit, local significance, and the richness it contributes to human diversity. True cultural appreciation lies in balancing the recognition of shared influences with a deep respect for the individuality of each culture.”

Meanwhile, Sudeshna Guha, a professor in the Department of History and Archaeology at Delhi’s Shiv Nadar University, called for a re-examination of territorialised historical narratives. Speaking to South First, Guha argued that India’s historical discourse, particularly regarding the IVC, has often been shaped by “a North Indian bias.”

She criticised nationalist and politically charged claims over the IVC, asserting that these narratives frequently ignore the interconnected nature of Bronze Age civilizations across the Indian subcontinent.

Guha described the Bronze Age, including the IVC, as an archaeological phenomenon. “The Aryan claim, the Indo-Aryan language group, is all based on spurious colonial history,” she said. “How can no one have deciphered the script if it’s so central to these claims?”

She proposed moving away from their spatial geographies as parts of modern nation-states. “The Bronze Age world was far more interconnected than we often give it credit for,” she said, urging researchers to critically assess biases in historical interpretations and continue studying the Indus Civilization as a complex phenomenon, rather than reducing it to political or territorial claims.

(Edited by Dese Gowda)