Published Jul 10, 2025 | 7:37 PM ⚊ Updated Jul 10, 2025 | 7:37 PM

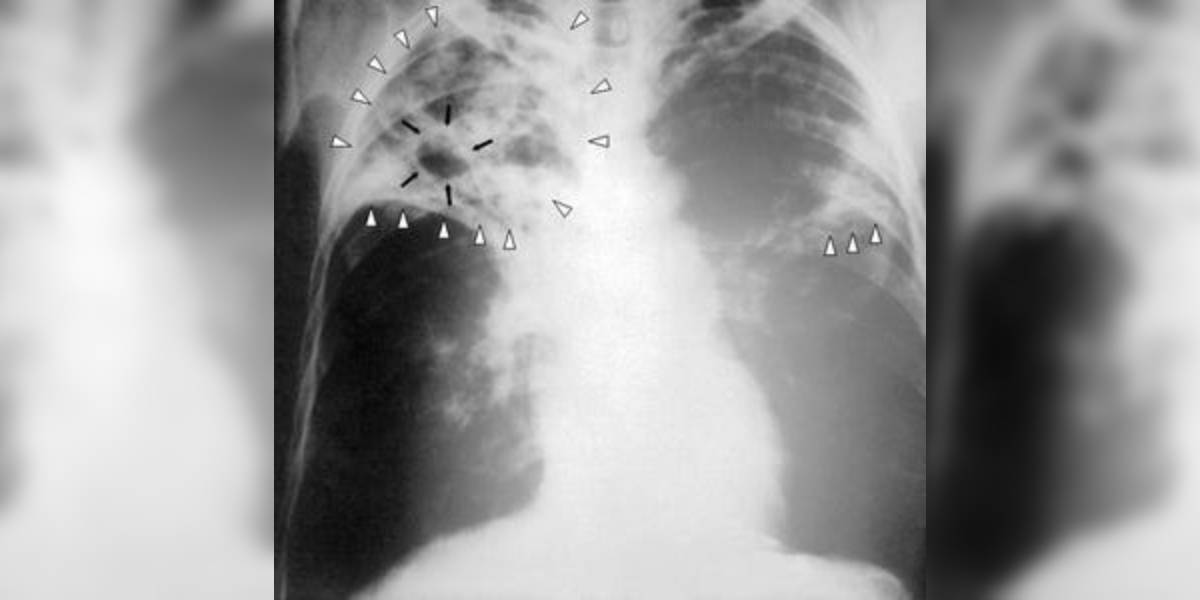

India's focus in on early detection of tuberculosis, timely treatment and improved patient support.

Synopsis: India, the country with the highest global burden of tuberculosis, aims to eliminate TB this year, five years ahead of the global target of 2030. This ambitious goal, led by the National TB Elimination Programme, focuses on early detection, timely treatment, and improved patient support.

Tamil Nadu has become the first Indian state to implement a tuberculosis (TB) mortality prediction model as part of its statewide programme to eliminate the disease, historically called consumption.

The state’s real-time triaging system marks a crucial step forward in India’s efforts to reduce TB-related deaths.

The model, developed by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR)’s National Institute of Epidemiology (NIE), uses five simple clinical signs to assess the sickness level of a newly diagnosed TB patient. These include body mass index (BMI), swelling in the legs and feet (pedal oedema), respiratory rate, oxygen level (saturation), and whether the person can stand without support.

Health staff enter this information into a digital platform called Severe Tuberculosis Web Application (TB SeWA), which shows the risk of death for that patient. This helps frontline workers understand the urgency and act faster, especially in serious cases, allowing for early intervention, admission, and better care.

India, the country with the highest global burden of tuberculosis, aims to eliminate TB endemic this year, five years ahead of the global target of 2030. This ambitious goal, led by the National TB Elimination Programme (NTEP), focuses on early detection, timely treatment, and improved patient support.

According to the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare’s India TB Report – 2024, TB case notifications increased by 16% in 2023, suggesting better tracking. The report also noted that over 93% of notified patients have already begun treatment.

In April 2022, Tamil Nadu started the process to implement a triage-based system to reduce TB deaths by identifying and prioritising patients who appear severely ill at the time of diagnosis.

Speaking to South First, Dr Asha Frederick, the State TB Officer, said the rise in TB deaths during the post-Covid-19 phase was not just because of TB alone, but also due to other coexisting health issues. The new model, under the TB Kasanoi Erappila Thittam (TN-KET), allows health workers to assess the severity of illness using five triage variables.

This early triaging is crucial because TB deaths in Tamil Nadu rose sharply during the late phase of Covid-19. “We found that many TB patients were dying not just due to TB but because of additional health conditions like diabetes or liver issues,” Dr Frederick said.

The new system helps staff identify patients who appear physically weak or severely undernourished and guide them toward urgent hospital admission.

At the time the model was introduced, most TB patients in Tamil Nadu lacked access to inpatient care in local government hospitals. Admission was possible only in medical colleges or a TB-specialised sanatorium. To change this, the TB programme worked with the Directorate of Medical Services to allocate dedicated beds for TB patients in taluk hospitals and sub-district centres, wherever qualified physicians were available.

“We wanted additional beds. We requested the directorate of medical services to identify such beds wherever there are physicians,” Dr Frederick said. Covid-time beds were also reallocated to accommodate TB patients.

When the patient’s BMI is critically low — below 14 — the state advises therapeutic nutrition. These patients are usually too weak to chew or swallow solid food. In such cases, health staff administer Formula 75 (F-75), a WHO-recommended therapeutic high-nutrition mix, to stabilise the patient.

“Some of them are so sick, they can only have things like gruel. F-75 is a powder which is made into a liquid and given to patients who can’t chew. It’s not just a supplement. It’s the only thing they could eat,” she said.

Once patients show signs of improvement and can consume regular food, they are shifted to a special high-protein TB diet. This includes eggs, milk, and legumes, along with their regular meals.

Tamil Nadu has made it mandatory for patients flagged as high risk to be in the hospital for at least seven days. “We say a minimum of five to seven days. If they’re fine in five, they may ask to leave. But we make sure they’re stable first,” Dr Frederick said.

The family is provided with counselling when patients are reluctant to get admitted. While there are no formal counsellors, TB staff have been trained in communication skills.

“We have provided our staff soft-skill training on counselling,” Dr Frederick said. Patients are made aware of the importance of admission and managing additional illnesses like diabetes. Severely undernourished patients are also prioritised for additional nutritional support through NGOs and local donors under the Prime Minister’s TB Mukt Bharat Abhiyan.

While some patients initially resist admission, the triage model has helped motivate staff to take the situation seriously. Dr Frederick explained that the death prediction score gives frontline workers a sense of urgency.

“Somehow, they try to convince the patient. The score helps them to realise that they must save this person,” she added.

In Tamil Nadu, Makkalai Thedi Maruthuvam (MTM) volunteers are already conducting door-to-door screening for non-communicable diseases. ‘They will be additionally asking the questions for TB,’ Dr Frederick further said, pointing to how the state is expanding community-level surveillance using existing health outreach systems.

A notable decline in TD deaths is reported from districts where the model has been effectively implemented. The death rates dropped from 7% to nearly 4.7%. However, Dr Frederick emphasised that this must be a sustained effort.

“The model does not work on its own; it is only as effective as the action it inspires among staff and doctors,” she added.

“Lots has to be done for differentiated TB care. Tamil Nadu is doing it, other states also have to do it,” Dr Hemant Deepak Shewade, Senior Medical Scientist at Division of Health Systems Research, ICMR-NIE, told South First.

This statement sets the tone for Tamil Nadu’s approach: The burden of action lies with the system, not the patient.

Unlike conditions like diabetes or HIV, TB programmes in India have rarely recorded the nutritional status of patients systematically. “Unless we record the levels of undernutrition, how will we even know if the most vulnerable people are being reached by nutrition support?” Dr Shewade asked.

Without basic data like BMI, it is impossible to assess whether direct benefit transfers or food baskets are going to the people who need them most.

Dr Shewade emphasised that extremely undernourished patients need a different form of support. “Formula 75 is not something that could be given to patients at home. It has to be given in a hospital where they are monitored until they improve enough to move on to solid food,” he added.

This is where inpatient care becomes crucial. “Therapeutic nutrition requires admission, supervision, and a phased recovery; it’s not just about handing over a packet of food,” he explained.

Tamil Nadu has made this possible through its differentiated TB care model under TN-KET. About 5% of TB patients in the state are found to be extremely undernourished. Without proper intervention, they have 10% to 30% chance of dying.

Yet, media narratives often miss this crucial point. “The media keeps saying, ‘give food’, ‘eat protein-rich food’. But the question is ‘can the patient even eat?’” Dr Shewade noted that oversimplified messaging tends to blame the patient rather than asking whether the system is equipped to help them survive.

“If a patient can’t stand without support, it’s not the time to lecture them about nutrition. It’s time to admit them to a hospital and act fast.”

The TB mortality prediction model is key to this process. It gives health workers a clear signal based on real indicators about how sick a patient is and how quickly they must intervene.

“If a staff member sees the probability of death is 30%, they will understand the urgency. They won’t delay admission or care.” This eliminates guesswork and builds accountability into the system.

“Health staff can use this number to push for beds, food, and transport. When the system knows the risk is high, it can’t ignore the patient,” Dr. Shewade added.

TB SeWA, which hosts this prediction model, acts as a live decision-making tool embedded into Tamil Nadu’s existing TB care framework.

He further warned that unless this approach is replicated in other states, deaths among the most vulnerable patients will continue unchecked. “Just saying that 70% of people got food is not enough. What about the remaining 30% who are dying? Were they too sick to ask? Were they ever recorded?”

Dr Shewade also noted that the key issue is not whether a patient lives in an urban or rural area, but how well the local health system functions. He observed that urban centres are often overcrowded, and access may be just as challenging as in rural areas if the system isn’t responsive. “Differentiated TB care is not about what the patient does, but what the health system enables,” he stressed.

Tamil Nadu has shown that reducing TB deaths is possible when urgency meets system-level action. Its model offers a clear, practical roadmap, one that other states must adopt with urgency, especially as India faces the world’s highest TB burden and a fast-approaching 2025 elimination target.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).