The Anganwadi workers claimed that they have been told to complete the SIR-related work within a week. They said the time is not adequate to meet all the voters.

Published Nov 12, 2025 | 12:06 PM ⚊ Updated Nov 12, 2025 | 12:06 PM

First undertaken in Bihar ahead of the state assembly polls, the SIR had sparked widespread protests and opposition.

Synopsis: Anganwadi workers who have been assigned the Special Intensive Revision duties work extra hours for a pittance. They said they were not given proper training or adequate tools to complete the task.

K. Nirmala has been working at an Anganwadi for the past 15 years. Every day, she travels from her home in Tambaram to Teynampet, arriving by 9 am to receive and take care of the children. After the Anganwadi closes at 4 pm, she heads home, usually reaching between 6 and 7 pm.

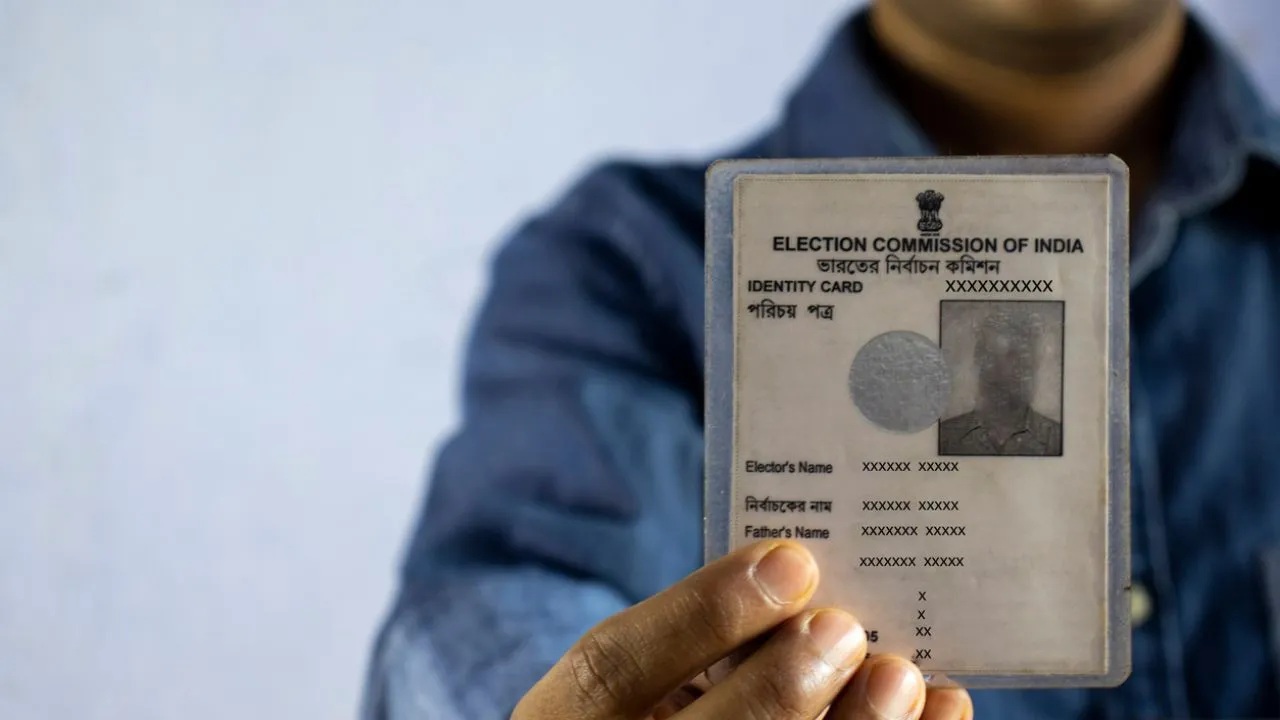

Today, her routine has been severely disrupted due to the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls currently being conducted by the Election Commission of India.

“I have to manage the children at the Anganwadi in the morning and then, by around 3 pm, I have to go to nearby localities and distribute voter revision forms to the 1,200 voters assigned to me,” Nirmala said.

“I must ensure that they fill the forms properly, collect them, and then upload all the documents on the Election Commission’s app. By the time I complete the work and return home, it will be around 10 pm,” she added.

For a meagre monthly salary of ₹10,000, Nirmala is one among thousands of Anganwadi workers across Tamil Nadu who have been assigned to the voter revision drive that began on 4 November.

Besides Anganwadi workers, corporation employees, ASHAs, and field staff from other departments have also been deployed. In total, 68,467 Booth Level Officers (BLOs) are involved in the exercise. They are expected to distribute, collect, and upload all the voter revision forms by 4 December.

However, the BLOs said they had not received proper training, equipment, or sufficient time to complete the task.

“Even a small mistake could lead to officials blaming us entirely,” a few Anganwadi workers said, expressing frustration over the burden placed on them.

According to the latest data from the Tamil Nadu Department of Social Welfare, there are 54,449 Anganwadi workers in the state.

Their pay is determined by years of experience—but even that is modest. Workers with up to 10 years of experience earn between ₹9,000 and ₹12,000, while those with around 20 years of experience earn ₹18,000–₹20,000.

Their responsibilities are extensive: they open the Anganwadi, take care of the children, provide nutritious meals, ensure immunisations are administered, and communicate regularly with parents.

With the government’s Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) going digital, workers must now upload daily data about every child’s progress on a mobile application.

Beyond this, they are also routinely assigned government duties such as voter verification, door-to-door surveys, and data collection. For such additional work, they are paid only ₹7,150 per year, though the government recently announced an increase to ₹12,000. But, as workers pointed out, “We don’t know when this will actually take effect.”

Now, they have been roped into the Election Commission’s special voter revision exercise—again, without proper training, equipment, or time.

Anganwadi workers said they were being pushed to complete two full-time jobs at once.

“I have to open the Anganwadi by 9 am and look after the children. After that, I go door-to-door to meet my assigned 1,200 voters, distribute forms, and answer their questions. It takes at least 15 minutes per house. Even visiting 50 houses a day is exhausting,” Nirmala said.

Another worker, who requested anonymity, said, “We’ve been told to complete all this within a week. They’re asking us to cover 300 houses per day! But even 100 to 150 houses are difficult. There’s no exception for women workers either. The pressure is unbearable.”

Most Anganwadi workers have completed only Class 10 or Class 12, and only a few appointed after 2017 are graduates. Despite this, they are now required to help voters fill out forms, verify details, and upload documents using the mobile app.

The Election Commission’s official schedule mentions that training and preparation were to take place between 28 October and 3 November, but both Nirmala and other workers say they received no proper training.

“They only told us how to give and collect the forms—nothing about how to fill or upload them,” one worker said. Nirmala added, “We weren’t given a full-day session. Just a half-hour briefing by the zonal officials.”

South First visited a voter assistance centre in Alandur, Chennai. When asked how a voter could correct an error in the existing records, the BLO did not seem to know the process.

According to the Election Commission, the BLO would guide the voter to make such corrections.

“You’ll have to handle it yourself. Whatever you submit now will appear in the draft list. Corrections take time—just fill out what you have for now,” the BLO at Alandur said. When asked for details on how to correct errors, the BLO admitted, “We weren’t told about it.”

Nirmala later added, “They said there might be a special camp in December—people can correct it then.”

If voters have already moved to another area, they are still required to travel back to their previous locality to meet the BLO, collect the voter revision form, fill it out, and submit it there. As a result, the public has to undertake several additional steps to complete this process.

If corrections need to be made later through separate camps, it becomes an added burden for them. However, there are no clear answers about this procedure, as even the BLOs themselves have not been provided with proper instructions or information.

Nirmala said most Anganwadi workers are mentally and physically exhausted, struggling to answer voters’ questions due to a lack of clarity and guidance.

Under the voter revision programme, BLOs must scan and upload filled forms using the Election Commission’s mobile app.

But, the workers claimed that they haven’t been given any mobile devices or data support.

“The mobile phone is crucial for this work. The ones given to us earlier by the state government barely function. We’ve been using our personal phones and paying for mobile data from our own pockets. Even the Election Commission told us to use our personal phones,” Nirmala said.

Many Anganwadi workers still use basic button phones and are unfamiliar with smartphones. “It’s hard enough for them to record daily child data, let alone upload thousands of voter forms,” one worker adds.

They urged the Election Commission to provide functional smartphones and internet connectivity for the work.

Each BLO has been assigned about 1,200 voters. They must visit every home, distribute the forms, ensure they are filled correctly, collect them, and upload the data.

“They ask us to report by 6 am and work till 9 pm, forcing us to finish the work within a week. It’s extremely tiring,” a BLO said.

“Our mobile numbers are printed on the forms without our consent. People keep calling us all day. It’s chaos. Each house takes at least 15 minutes—how can anyone finish this in a week?” Nirmala asked.

In some areas, several voters have not even received their voter revision forms, the Anganwadi workers said.

“The forms are missing for a few households, and we are unable to respond when those voters ask us about them. The forms are not arranged in any proper order either — it takes a lot of time just to search for and locate the right ones before we can distribute them,” they explain.

According to the Election Commission’s guidelines, a BLO must visit each household at least three times. In reality, many visits take longer due to residents being away or delays in filling out the forms.

By Nirmala’s estimate, even if a BLO works eight hours a day, they can only visit about 32 houses. Working 16 hours might cover 64 houses, and even 24 hours nonstop wouldn’t exceed 96 houses—far short of the 300 daily target fixed by zonal heads.

Anganwadi workers demanded more time, proper tools, and fair compensation for the extra workload.

“This is called a special revision, so it should be done properly. If something goes wrong, we’ll be blamed. If a voter’s name doesn’t appear later, they’ll call our number asking why. Officials will just hold us responsible and move on. We need adequate time,” Nirmala said.

They also asked for mobile phones, internet access, fair pay, and reimbursement for expenses incurred during this process.

“Superiors treat us badly. If we request a day’s leave because of health issues, they threaten us saying, ‘This is election duty—if you don’t do it, you’ll lose your job,’” Nirmala said.

She added that many workers were now mentally and physically drained. She urged the government to take immediate action to address their concerns.

When asked, Social Welfare Minister Geetha Jeevan said she would respond later.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).