Published Jun 03, 2025 | 9:35 AM ⚊ Updated Jun 03, 2025 | 9:35 AM

Rm Palaniappan. (Supplied)

Synopsis: Rm Palaniappan’s works reflect his interest in Physics and Philosophy. They are also testimony to his curiosity to see for himself the changing landscapes as he cuts across longitudes and latitudes. He spoke to South First about his perception of the world, time, sound, space, and, of course, his works.

There is geometry, there is physics, and, of course, there is philosophy.

Lines and geometric abstractions are the lifeline of Rm Palaniappan, a senior artist from Chennai, whose works often reflect science, memory, and philosophy with a distinctive sense of luminosity.

In conversation with P Sudhakaran, Palaniappan, who had served as the Regional Secretary of the Lalit Kala Akademi, speaks about his evolution as an artist and the visions and philosophies that have shaped his creative journey.

Q: You began your career as a figurative artist and transitioned to using mostly geometric lines. How was that transition?

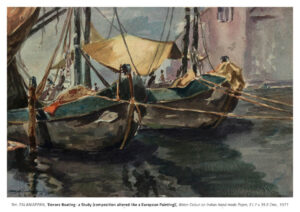

A: I came to study art at the College of Arts and Crafts in Madras in 1975. Back then, I aspired to work like the old masters, whose reproductions I had seen earlier. When I came to Chennai, I came across the works of a few British masters in museums, including the Port Museum. In this way, I began working in this style.

Ennore Boating (1977), a work by Palaniappan. (Supplied)

One of my teachers, Vijaymohan, who taught us in Madras, taught us how to draw a full figure with precision. When I began to understand the importance of negative space, I realised how crucial both positive and negative space are in conceiving any visual composition. So, when I started creating my compositions, I began applying those ideas in my work.

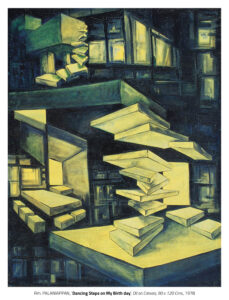

In 1979, I had to create a composition as part of a classroom exercise. I didn’t know what to do because at that time, I needed a reference to make a painting. During our leisurely walks to the local hotels for food, my friend would talk about composition. One day, on my next visit to a hotel, I noticed a spiral staircase that struck me as very elegant. I asked myself: if there were no connection between the two steps, what would happen? Why doesn’t the step fall? I felt it was

flying. That’s when I realised there is a kind of density in the air – something that holds it all together.

Q: Coming to the lines in your compositions, they are directly related to Mathematics and Physics. But they often take on a philosophical and Tao dimension, as reflected in your work. How do you connect this kind of philosophy with your passion for science?

A: I studied Mathematics and Science in school and pre-university, and they became a part of my life. As you have mentioned, philosophy is also something I deeply connect with. I cannot separate these three – science, art, and philosophy – and I think they are intertwined.

‘Dancing Steps on My Birthday – 1978. (Supplied)

There is an invisible chemistry of the line, and perhaps this is the result of my wide reading, from the Upanishads to philosophy to physics. Yes, there is an underlying vision of Tao in my work.

When we speak of straight or curved lines, their dimensions and perspectives are important to me. Because when we talk about perspective, it is not only physical; it is psychological too.

Further, the idea of the infinite is very much important, and my latest show at Nature Morte Gallery in Delhi is named ‘Finite and Infinite’. My recent retrospective exhibition in Chennai was titled ‘Mapping the Invisible’, and the concept of the invisible also has an element of infinity to it.

As is the case with the line, time also has a linearity. But your compositions often break our concept of the linearity of time and space.

Yes, this happens because my basic understanding of space is linked to the infinite – first the universal space, and then infinity itself. When I was very young, there was an old chair in my house, a chair that only my grandfather used to sit in. After he went for dinner in the evening, I would sit in that chair in the open courtyard and gaze at the vast sky. At that young age, I always wondered what lay beyond it. Even now, that question stays with me: What is behind that? What is infinity?

Rm Palaniappan. (Supplied)

Earlier, in my compositions, there was often a window-like structure. From 2000 to 2008, I worked with lines – lines flying through open space, universal space. In my recent works, the space is more confined. So, life exists in confined spaces, whether your life or mine. We have been given an extension of life, which we pass on to others. It is like infinity – the birth of life on Earth. At the same time, I want to bring my physical experience into my compositions. The

crossing lines represent our experience of seeing things, the physicality. The psychological experience, in turn, appears as light in my compositions – the line as light.

Q: When you talk about the line as light, it reflects a curious aspect of your works. The luminosity that you bring about. How do you bring about this?

A: It depends on your focus while you work. When you make a line with a pencil, you are focusing on the movement. Within that movement, there is light, and when you open that light, whatever its luminosity may be, you become part of it. That light may start from one point and end somewhere, and as you do this, you lose track of time. That is the physicality of the line. But when you enter the line as light, the dimension breaks. The reality becomes something entirely

different, and the psychological impact of your presence in that movement becomes visible.

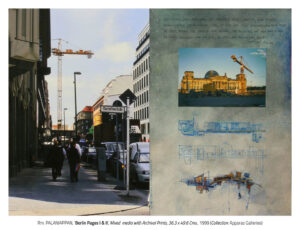

Q: Unlike your present works, some of the drawings in the series, ‘New Berlin – On Process’, done after your visit in 1999, do not use straight lines but loosely flowing strokes. But they have a geometric dimension at the same time, reflecting your philosophy and experience.

A: Yes, there is a shift in the approach in that series. It wasn’t just about experiences – it was a realization of seeing a place I had earlier only experienced in films. In my earlier days, I used to watch war movies and science fiction.

Berlin Pages I & II – 1999. (Supplied

I remember a 1950 film, The Fall of Berlin, based on the Second World War. At the time, I had no idea who was fighting whom in the film. I vividly recall a scene where a building collapsed in a fire following continuous firing. Many years later, when I visited Berlin, I had the chance to stand in front of that building – the Reichstag, which housed the German parliament. The Soviet forces had taken control of the building at the end of World War II and raised their flag there.

When I visited, the building was undergoing reconstruction, and this had a deep impact on me. There were construction machines all around, and tourists were snapping photographs. I, too, took photographs, moving forward and backward. I felt like I was creating a drawing on the floor space alongside others. I wanted to document that moment in a set of drawings, which you refer to now. I put a red line on top of every print in this series to represent my presence as part of the composition.

Q: How was your foray into printmaking?

A: I was into graphics in my early career. Then I got an opportunity to meet Krishna Reddy, the pioneer in viscosity techniques in printmaking. He was conducting a workshop at Chitrakala Parishath in Bangalore (now Bengaluru). It was Nanjunda Rao, who knew my work well, who recommended me to Krishna Reddy. So, I joined the workshop as an assistant.

Mystical Truth – 2023 (Supplied)

It turned out to be a great opportunity – not only to interact closely with Krishna Reddy but also to see his works firsthand, as there was an exhibition of his art running alongside. I was a curious young man then, always eager to learn. I would ask him how he achieved a particular colour or effect, and he would generously explain everything in detail. He recognised my interest and understanding of printmaking and one day said, “Palaniappan, you are going to take a print for everybody in the workshop.”

I printed for nearly 30 participants over two days. For each print, I had to work with three rollers. It became a kind of meditative process. You have to understand the weight of each roller, the density of the rubber, the viscosity of the ink – you even have to centre yourself mentally, to maintain body equilibrium. These are all things I began learning from him and applying as per his guidance.

Krishna Reddy had such mastery that he could tell, just by the sound of the roller, whether I needed to add a few drops of colour or adjust the viscosity. I was amazed – how could someone recognise the density of a particular ink just by sound!

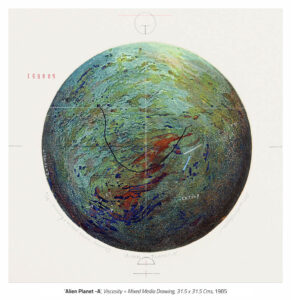

That’s when I realised that sound also has a language. That’s how it began. I made one circle – like a planet – something that people often talk about, though few truly understand. Even before this, I had done some etchings and drawings of planets, too.

A: You are right, there is a cartographic element in my works. There are many reasons for this, and my dimensions are quite different from conventional interpretations.

Alien Planet-A – 1985. (Supplied)

As a child, I was fascinated by science and war movies, particularly the motion of aircraft and the drama behind them. When a flight takes off, the mapping of the land beneath becomes incredibly important.

For me, it is not just about physical mapping but also psychological mapping. My first flight was to New York City in 1990, and ever since, I’ve flown hundreds of times. Each time, I look down at the map of the land beneath me, this has significantly altered the dimensions and visual impact of my paintings.

When I returned from flights, I started making freehand drawings, and patterns began to emerge. I would draw crisscrossing lines, and being an artist, I have a lot of experience in compositions. I would start with abstract drawings, and then I would add architectural patterns.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).