Since the 1970s, coalition politics has become the norm in Indian parliamentary governance at the Centre. Tamil Nadu, however, has stood apart. Coalition governments or power-sharing arrangements have never found traction with its electorate.

Published Apr 22, 2025 | 9:00 AM ⚊ Updated May 24, 2025 | 7:42 PM

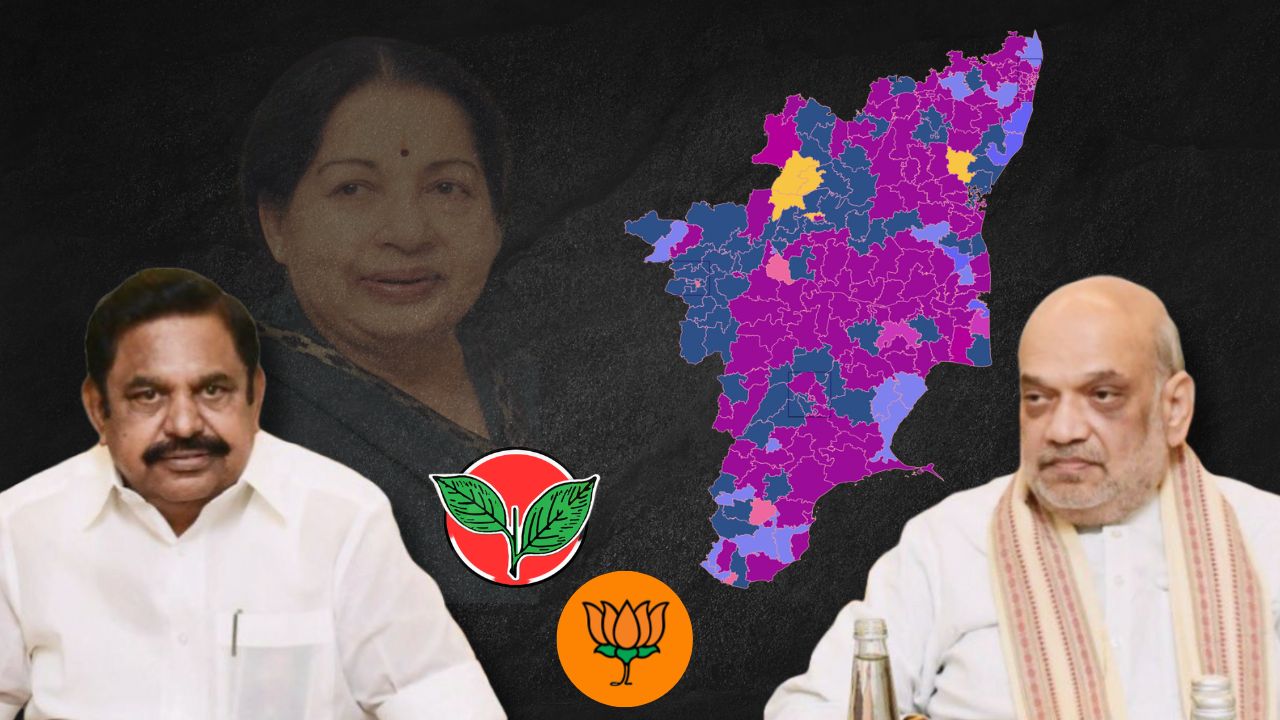

Synopsis: In a dramatic reversal of its late leader Jayalalithaa’s vow never to align with the BJP, the AIADMK entered a coalition with the party ahead of the 2019 Lok Sabha elections – only to suffer continuous electoral setbacks since. The alliance ran counter to decades of Tamil Nadu’s political instincts, where voters have consistently favoured strong, single-party governments capable of safeguarding their rights and interests over fragile coalitions. As the two parties join forces once again ahead of the 2026 elections, the question remains: will the AIADMK fare any better this time?

On 4 July 1999, a conference on Muslim rights took place at Chennai’s Marina Beach.

Addressing the gathering, then Tamil Nadu Chief Minister and All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) General Secretary J Jayalalithaa made a striking declaration:

“I give my Muslim brothers a guarantee. I made a mistake in the past, and I have the courage to admit it. I toppled the BJP [Bharatiya Janata Party] government as an act of penance. From now on, the AIADMK will never have any ties with the BJP.”

After the 1998 Lok Sabha elections, the AIADMK had extended crucial support to the BJP, helping to form the Vajpayee-led government at the Centre.

Her decision to withdraw support in early 1999 led to the fall of that government and triggered fresh elections.

Jayalalithaa upheld her vow as a matter of personal and political principle for the rest of her life.

Fast forward to 21 April 2014, during the Lok Sabha election campaign in Chennai, she drew comparisons between the development models of Gujarat and Tamil Nadu:

“Tell me now, who is the better administrator, Modi or this lady?” she asked the crowd.

Even when the BJP was not a direct rival in Tamil Nadu, she used the moment to pitch herself as a peer to the party’s national leadership, emphasising her administrative credentials.

Yet, within three years of her death in 2016, the AIADMK – even as it frequently invoked her legacy as “Amma” – entered into an alliance with the BJP ahead of the 2019 Lok Sabha elections.

It was a sharp reversal of Jayalalithaa’s long-held stance and the solemn pledge she had made to the people of Tamil Nadu.

While political realities often demand a degree of flexibility, the AIADMK leadership, marred by internal divisions and lacking Jayalalithaa’s stature or mass appeal, enabled what had once been politically unthinkable.

The electorate, however, did not embrace the new alliance. In the 2019 general election, the AIADMK secured just one seat – Theni.

The losses continued into the 2021 Assembly elections. Despite contesting in partnership with the BJP and Pattali Makkal Katchi (PMK), the alliance faced another setback.

The AIADMK and its allies contesting under its symbol won 66 seats, while the PMK claimed 5 and the BJP 4.

It was a steep decline from 2016, when the AIADMK, under Jayalalithaa’s leadership, had secured 134 seats on its own.

Ironically, the BJP re-entered the Tamil Nadu Assembly with the same number of seats – four – that it had last won in 2001, then in alliance with the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK).

In 2016, the AIADMK had polled 40.88 percent of the vote. By contrast, the BJP and PMK, contesting separately, managed 2.9 percent and 5.4 percent respectively.

In 2021, the AIADMK’s individual vote share dropped to 33.29 percent. Alongside its allies, the combined figure stood at 39.71 percent – a fall of nearly 9.5 percentage points.

The BJP’s numbers remained modest. It contested 20 constituencies and polled 2.62 percent of the vote – slightly lower than its 2.9 percent share in 2016, when it had fielded candidates in 187 seats. On that metric, some may even consider the result an incremental gain.

In 2001, the BJP had secured four seats as part of a losing alliance led by the DMK. In 2021, it repeated that outcome under AIADMK-led coalition.

Thus, the AIADMK-BJP alliance appears to have done more to advance the BJP’s prospects than its own.

Now, after a brief hiatus, the two parties have announced a renewed alliance ahead of the 2026 Assembly elections. At a recent press interaction, Union Minister Amit Shah went so far as to declare that Tamil Nadu will see a coalition government.

That raises a larger question: what does Tamil Nadu’s electoral history say about its political instincts? And what kind of leadership do voters in the state ultimately gravitate toward – and why?

Since the 1970s, coalition politics has become the norm in Indian parliamentary governance at the Centre. While such arrangements have led to occasional instability, they are now widely accepted as necessary – and often better than single party majorities for federalism and governance.

Tamil Nadu, however, has stood apart. Coalition governments or power-sharing arrangements have never found traction with its electorate.

As the DMK’s enduring slogan puts it: “Coalition at the Centre, Self-autonomy in the States.”

In 1967, Tamil Nadu saw the formation of its first non-Congress government. Since then, across all 13 Assembly elections up to 2021, the people have consistently handed a clear mandate to a single party – though the Congress has never returned to power since.

Here is a look at the number of seats won by the victorious party in each election since 1967:

These figures make it clear: the electorate has alternated between the two dominant Dravidian parties – the DMK and AIADMK – while hung assemblies have been firmly avoided.

Writer and political commentator AS Panneerselvan traces this trajectory back to the first general election after India became a republic, in 1952.

“In that election, though the Congress did not secure a majority, it managed to cobble together support from the Commonweal Party, the Labour Party, and Independents aligned with the DMK to form a government,” he explains.

“This experience taught the Dravidian parties the importance of securing a clear majority on their own. From then on, they worked toward that goal.”

He points out that over the years, several state governments have been dismissed or undermined by governors relying on the strength of the second-largest party.

“This trend has only intensified in the past decade. Maharashtra is a case in point, where the governor played a key role in splitting the Shiv Sena,” he says.

“Governors today have become direct participants in state politics. It is with this understanding that voters in Tamil Nadu, since the 1970s, have always backed a single party to govern.”

Panneerselvan underlines that Tamil Nadu’s electorate actively considers whether coalition politics will benefit or harm them.

“Tamil Nadu’s electorate has never created a scenario where the second-largest party could wield power to threaten or destabilise the government. Whether it is the DMK or the AIADMK, the people have consistently shown their full support for a single-party government,” he asserts.

Political analyst Xavier echoes this view, noting that coalition governments ultimately come down to numbers.

“Take Maharashtra for example – whether the Shiv Sena and BJP form a coalition depends purely on their combined strength. Similarly, in Tamil Nadu, one of the recurring debates is whether to offer Thirumavalavan the post of Deputy Chief Minister,” he says.

“But when a party does not have the numbers, is there any rationale for making such a concession?”

He also questions the popular understanding of coalition politics:

“What does a coalition government truly mean? For the people, the key concern is: what do they gain from the alliance? It is not just about how many ministerial posts a party gets, but whether the alliance can deliver tangible benefits to their constituencies. That is what matters most.”

Crucially, Tamil Nadu’s electorate has shown little appetite for political experimentation. Whether it was the Tamil Maanila Congress in the 1990s or the Makkal Nala Kootani in 2016, voters have consistently withheld significant support from such alliances.

Their choices reflect a clear rationale – who to support, with whom, and why.

“Tamil Nadu’s politics has always been unique. The reason we do not follow national trends lies in the socio-economic and political conditions of the state,” Social researcher and political commentator Gladston Xavier explains.

“After Independence, when the Congress era under Kamaraj faded and the DMK filled that space, Tamil Nadu’s politics became bipolar. More significantly, it became personality-driven. Voters embraced strong personalities as leaders. This is largely due to two reasons: one, the bargaining power of these leaders is perceived as strong. Two, their ability to deliver on promises is clearly demonstrated.”

Panneerselvan offers a complementary view: “For Tamil Nadu voters, the choice of who should govern them often hinges on whether a relationship with the central government will be beneficial or harmful to the state.”

He continued: “Their stance on this is quite clear. Tamil voters hold a strong belief: they will not support a remote central leadership. Instead, they prefer to back a regional party that they believe will protect their interests. For Tamil Nadu’s electorate, it is not just about leaders as individuals, but more about: ‘Can you protect our rights?’ That is the real criterion when they choose their leader or party.”

He points to the controversy around the National Eligibility cum Entrance Test (NEET) as a case in point.

“Whether it was during Karunanidhi’s tenure or Jayalalithaa’s, neither was able to implement NEET in the state. But at the very least, they secured exemptions. After their demise, no such effort was made. The AIADMK leadership that was in power at the time did not even attempt to push the issue to the point of seeking an exemption,” he says.

“Not just that, take issues like the abrogation of Article 370 in Kashmir or the National Register of Citizens (NRC). On every front, the AIADMK failed to take a clear stand against the BJP. As far as I know, post-Jayalalithaa, the only time the AIADMK voted against the BJP was on the Waqf Board Bill. Yet even then, the party did not publicise its stance or claim to have stood up for minority rights. Nor did the BJP speak of it.”

The pattern is evident: voters in Tamil Nadu closely observe the actions – and inactions – of political parties. Their support hinges on performance, clarity, and a demonstrated commitment to protecting the state’s rights.

According to the 2011 Census, Muslim communities alone make up over 5 percent of Tamil Nadu’s population.

With the recent passage of the Waqf Board Amendment Act, this demographic has become a focal point of contention within BJP-led alliances.

Notably, while the AIADMK voted against the Bill in Parliament, it announced an alliance with the BJP just a week later.

The Social Democratic Party of India (SDPI), which had previously aligned with the AIADMK, subsequently declared that it would not ally with any BJP-led coalition.

This has sparked questions over whether the AIADMK is at risk of losing its long-held image as a party that safeguards minority interests in the state.

“In Tamil Nadu, caste-based or religion-based calculations do not determine victory or defeat,” Panneerselvan explains, citing Mayiladuthurai as an example – the constituency with the largest Vanniyar population in Tamil Nadu.

“Despite this, no Vanniyar candidate has won any election in that constituency. The reason for this is the uniqueness of Tamil Nadu’s political landscape,” he adds.

“For instance, did only minorities in Tamil Nadu oppose the Waqf Board Bill? No, everyone opposed it. Similarly, caste and religious factors may occasionally appear in some cases. Take, for example, the untouchability wall in Uthapuram. We have heard of it, but the issue did not spread across all of Madurai.”

He continues: “But consider the Musapher Nagar riots. That created waves of unrest and disturbances across Uttar Pradesh. But in Tamil Nadu, despite such localised issues, they do not escalate into a widespread, state-wide problem. This is because of the century-long tradition of social justice movements in the state.”

Former Chief Minister Edappadi K Palaniswami now faces the formidable task of reviving the AIADMK’s electoral fortunes – but without the charisma or widespread appeal that defined the party’s towering past leaders.

Can he become a mass leader in the mould of MG Ramachandran (MGR) or Jayalalithaa? Panneerselvan is unequivocal: “No.”

“Take MGR as an example. Initially, he contested from the St Thomas Mount constituency, but later contested in multiple constituencies like Ranipet, Madurai, and others. Similarly, if we consider M Karunanidhi, he contested from places like Thirukuvalai, Tanjore, and many other constituencies. Even Jayalalithaa contested in various constituencies,” he explains.

“These leaders could win anywhere in Tamil Nadu, as they were accepted as leaders by the people across the state.”

In contrast, he points out: “Edappadi, to this day, has not gone beyond Salem. This indicates that he has not been accepted by the people as a leader of Tamil Nadu as a whole.

“Moreover, if he were to win, it would be because of his social background, not as a leader representing all of Tamil Nadu. Therefore, his politics cannot be reduced to the politics of Tamil Nadu as a whole.”

Xavier, however, argues that Palaniswami has demonstrated a different kind of leadership – marked by perseverance in the absence of strong political backing.

“Even when people doubted if he could last six months, Edappadi managed to govern for four and half years,” he explains. “Unlike O Panneerselvam [a close aide of Jayalalitha who was once thought to be her successor], who had the support of party leaders, Edappadi did not have such backing. Regardless of whether he won or lost the next election, the fact that he stood firm in power is proof of his leadership.”

Regardless, both are clear about one thing: “Voters cast their votes for those who protect their rights. In 2026, the party that wins this trust will form the government.”

(Edited by Dese Gowda)