Under the direction of Periyar, Jeevanandam translated Why I Am An Atheist by Bhagat Singh. Later, he defended the Kamba Ramayanam at a time when the epic was publicly burnt by the Dravidian movement.

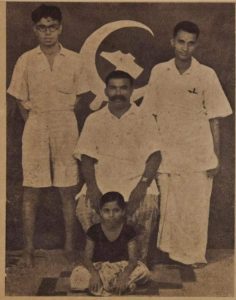

P Jeevanandam (right) is welcomed after his release from prison in Madurai in 1945. In the centre is S Ramanathan (Supplied)

Today is the 115th birth anniversary of P Jeevanandam (1907–1963), one of the tallest Communist leaders from Tamil Nadu.

Though the name of Jeevanandam is now indelibly linked to Communism, he was associated with many political movements.

Initially interested in the Gandhian nationalist movement, he was disillusioned with its social conservatism and was then part of Periyar EV Ramasamy’s Self-Respect Movement.

It was Jeevanandam who translated Why I am an Atheist by Bhagat Singh into Tamil under the direction of Periyar in 1934. The book was brought out by the publication house of the Self-Respect Movement. The title of the translation in Tamil read Naan Nathigan Yen?

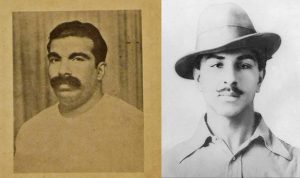

P Jeevanandam (Left) in Muthupet in 1940. When Jeevanandam was part of the Self-Respect Movement, he translated ‘Why I Am An Atheist’ by Bhagat Singh (Right) under the direction of Periyar (Supplied/Wikimedia Commons)

The British government in India framed charges and arrested EV Krishnasamy, the editor of the rationalist publication house and brother of Periyar, and Jeevanandam for translating the banned work of Bhagat Singh.

The value of this translation by Jeevanandam cannot be underestimated in popularising the views of Bhagat Singh.

Chaman Lal, the editor of The Bhagat Singh Reader, noted the following about the Tamil translation of the text, “During the 1947 Partition, issues of the people could not reach India for many years; this essay was banned later by the British colonial government. During those times, someone retranslated this essay from Tamil to English, which still continues to be in circulation on many websites, and from this, many further translations were done!”

Jeevanandam then split with the Self-Respect Movement over what he felt was its support for the pro-landlord, pro-imperialist and pro-capitalist politics of the Justice Party.

P Jeevanandam (Centre) at the Workers’ Congress in Vickramasingapuram in 1945. Standing on either side are Communists Baladandayutham (Left) and P Ramamurthi (Right) (Supplied)

In 1952, Jeevanandam contested the Legislative Assembly elections as a member of the Communist Party and won from the working-class constituency of Washermanpet in North Madras.

Veteran Communist leader N Sankariah (now 101 years old), in a profile by P Sainath for the People’s Archive of Rural India, has noted that Jeevanandam and P Ramamurthi were the first to speak in Tamil in the state Legislative Assembly.

Jeevanandam edited Thamarai, the Communist Party’s literary organ in the state, and composed a number of poems in Tamil.

Jeevanandam’s defence of Kamban’s Ramayanam is well known among literary enthusiasts.

He made an attempt to popularise the medieval Tamil poet Kamban and his Ramayanam to the Tamil public at a time when rival interpretations of the epic, amounting to its dismissal, threatened its place in the Tamil literary canon.

The ideologues of the Dravidian movement saw in the work of Kamban the degradation of Tamil literary culture under the influence of Aryan Brahmin culture.

On the contrary, Jeevanandam found in Kamban a democratic philosopher, humanist, and poet who gave powerful expression to the quest for justice and equality that has been an integral element of Tamil popular and literary culture.

Jeevanandam’s defence of Kamban became more aggressive in the decade of 1950s when he started to write and deliver lectures on various literary and public platforms as an itinerant Marxist activist and ideologue, mostly in response to the Dravidian movement’s dismissal of the poet on racial and cultural grounds.

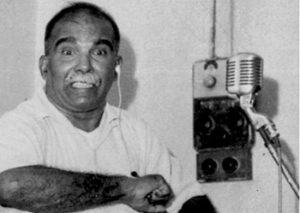

Jeevanandam (Left) found in Kamban a democratic philosopher, humanist, and poet who gave powerful expression to the quest for justice and equality (Supplied)

Periyar had presented Kamban as the slave of Aryans (Aryaccooli) who introduced the Brahmanic Aryan thoughts in the Tamil land. The Self-Respect Movement had even launched a campaign to publicly burn Kamba Ramayanam in 1943, among other works, despite protests by Tamil scholars such as Somasundara Bharathi and RP Sethu Pillai.

It is against this context that we need to situate Jeevanandam’s elaborate lectures on Kamban delivered at Karaikudi Kamban Literary Association annual meetings on Kamba Ramayanam in 1954 and 1955.

Jeevanandam showered praise on Kamban and considered him the friend of the cultivating class while explaining the humanism in the Tamil rendering of the Ramayanam. He argued that Kamban, in his description of the kingdom of Kosala, transposed the Tamil geography filled with the prosperity of agricultural production and trade.

Jeeva read, interpreted and communicated classical literature in Tamil. His engagement with Kamba Ramayanam was part of his wider cultural and literary activism (Supplied)

Kamban’s Ramayanam was an epitome of Tamilness, and this can only be possible when a poet mastered all the preceding literary and grammatical works in the Tamil language. Jeevanandam considered Kamban as a master literary figure who was well versed in the classical corpus.

The title of Kavi Chakravarti (emperor among poets) attributed to Kamban was not bestowed by Chola kings but by the people after he rendered the Ramayanam in Tamil, Jeevanandam said. He further argued that Kamban not only distanced himself from the Chola kings but also even criticised them.

Most importantly, the poet had inverted the Tamil notion of kingship, attributing it to a populist character. Jeevanandam contended that it was Kamban who wrote that the people of a kingdom constituted the life (uyir) and the king the body. He argued that the Tamil literary tradition until Kamban’s arrival considered the king as constituting life (uyir) and people as the body of the kingdom.

The clear inversion of kingship, for Jeevanandam, firmly places the social belonging of Kamban. Thus Jeevanandam highlighted the place of Kamba Ramayanam in the Tamil literary canon at a time when the epic was publicly burnt by the Dravidian (Self-Respect) movement.

Born in the village of Boothapandi in Kanyakumari district, Jeevanandam, or Jeeva as he was called, lived in a hut till he died.

When K Kamaraj was the chief minister of the state, he offered Jeevanandam government housing. The latter refused it, pointing to the thousands of people who didn’t have access to such a facility.

On 18 January 1963, the Communist leader who led a simple life passed away far too early, at the age of 56.

Apr 24, 2024

Apr 23, 2024

Apr 23, 2024

Apr 21, 2024

Apr 20, 2024

Apr 20, 2024