Published Dec 26, 2024 | 12:00 PM ⚊ Updated Dec 26, 2024 | 12:00 PM

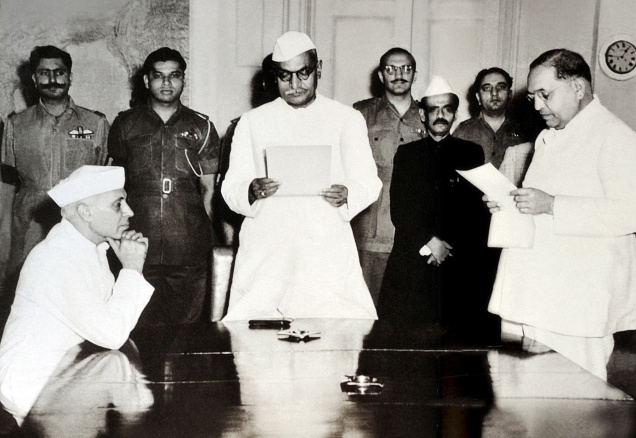

Ambedkar is sworn in as India's first Law and Justice Minister (Wikimedia commons)

Following Union Minister Amit Shah’s controversial comments in Parliament, where he criticised the repeated invocation of BR Ambedkar, the Opposition, particularly the Congress Party, has sought to position itself as a defender of Ambedkar’s legacy.

However, the Grand Old Party’s relationship with the Dalit icon, particularly the personal dynamics between Congress figures MK Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, was not as harmonious as some current leaders might wish posterity to remember.

Ambedkar’s views on the party, especially under the leadership of MK Gandhi, are best illustrated in his 1945 book, What Congress And Gandhi Have Done To Untouchables. In it, he outlines the party’s failure to address the plight of the Depressed Classes and offers a scathing critique of its policies:

“In 1917, the Congress passed a resolution acknowledging the ‘necessity, justice and righteousness of removing all disabilities imposed by custom upon the Depressed Classes.’ However, this resolution was soon forgotten. The Congress later washed its hands of the issue, relegating it to the Hindu Mahasabha.

“There could not be a body more unsuited to take up the work of the uplift of the Untouchables than the Hindu Mahasabha.”

Ambedkar also perceived the Congress Party as primarily representing the interests of upper-caste Hindus, sidelining the concerns of marginalised communities:

“The Congress’s policy was to avoid social reform. Despite Mr Gandhi’s insistence on the link between Swaraj and the abolition of untouchability, the Congress did not act to ameliorate the conditions of the Untouchables,” he wrote.

Ambedkar and Gandhi, both towering figures in India’s struggle for independence and self-determination, ostensibly shared a commitment to social justice but fundamentally diverged in their methods and vision.

Ambedkar, born into the Dalit Mahar caste, experienced untouchability firsthand, shaping his belief that true reform required the complete abolition of the caste system. He viewed caste as inherently oppressive, rooted in Hindu scriptures that legitimised discrimination.

In contrast, Gandhi acknowledged the evil of untouchability but did not advocate for the abolition of the caste system itself. He believed in reforming Hinduism from within and saw untouchability as a moral and social issue that could be addressed without dismantling the entire caste structure. Gandhi referred to the untouchables as “Harijans” (children of God) and initiated campaigns to improve their status within the Hindu society. However, he maintained that the caste system had a functional role in maintaining social order.

Their ideological differences became particularly pronounced during the debate over separate electorates for the Depressed Classes (Scheduled Castes). The British government’s Communal Award of 1932 proposed separate electorates for these communities, a move Ambedkar supported, believing it would ensure political representation and empowerment for the marginalised.

Gandhi, meanwhile, opposed the proposal, fearing it would fragment Hindu society. He undertook a fast unto death to protest against it, leading to the Poona Pact, where Ambedkar, under immense pressure, was forced to agree to a compromise involving reserved seats within a joint electorate.

Ambedkar felt that Gandhi’s approach was paternalistic and insufficient to address the systemic nature of caste oppression. In What Congress And Gandhi Have Done To Untouchables, he noted:

“This was nothing but a declaration of war by Mr. Gandhi and the Congress against the Untouchables. In any case, it resulted in a war between the two. After this declaration by Mr. Gandhi, I knew what he would do in the Minorities Committee, which was the main forum for the discussion of this question. Mr. Gandhi was making his plans to bypass the Untouchables and to close the communal problem by bringing about a settlement among the three parties—the Hindus, the Muslims, and the Sikhs.”

Ambedkar also criticised the Congress’s tactics during elections, accusing it of manipulating reserved seats for its own benefit and to legitimise MK Gandhi as the sole representative of the Dalit community:

“The Congress actively interfered in the elections to reserved seats for the Untouchables… [This had] a double purpose… In the first place, it was out to capture these seats to build up its majority, which was essential for enabling it to form a Government. In the second place, it had to prove the statement of Mr. Gandhi that the Congress represented the Untouchables and that the Untouchables believed in the Congress. The Congress, therefore, did not hesitate to play a full, mighty and, I may say so, a malevolent part in the election of the Untouchables by putting up Untouchable candidates on Congress tickets pledged to Congress programme for seats reserved for the Untouchables. With the financial resources of the Congress, it made a distinct gain.”

Ambedkar’s relationship with Jawaharlal Nehru was far more collaborative and marked by mutual respect, but still fraught with scepticism and disagreements.

Nehru appointed Ambedkar as Independent India’s first Law Minister in his interim government. However, Ambedkar often felt marginalised within Nehru’s cabinet, believing that his expertise and qualifications were disregarded.

In his detailed 1951 resignation letter, Ambedkar outlined his issues with the Nehru government and explained his decision to leave the cabinet:

“We used to call [Law Ministry] an empty soap box only good for old lawyers to play with… During my time, there have been many transfers of portfolios from one Minister to another. I thought I might be considered for any one of them. But I have always been left out of consideration.”

Ambedkar was also dissatisfied with the government’s inaction on safeguards for Backward Classes and Scheduled Castes.

“What is the position of the Scheduled Castes today? So far as I see, it is the same as before. The same old tyranny, the same old oppression, the same old discrimination which existed before, exists now, and perhaps in a worse form,” he writes.

The handling of the Hindu Code Bill became the final catalyst for Ambedkar’s resignation. He believed the Bill was deliberately delayed and ultimately dropped due to insufficient support within the Cabinet.

“In regard to this Bill, I have been made to go through the greatest mental torture. The aid of Party Machinery was denied to me. The Prime Minister gave freedom of vote, an unusual thing in the history of the Party. I did not mind it. But I expected two things. I expected a party whip as to time limit on speeches and instruction to the Chief Whip to move closure when sufficient debate had taken place. A whip on time limit on speeches would have got the Bill through.”

In the inaugural general elections of 1951-52, Ambedkar contested the Bombay North Central constituency as a candidate of the Scheduled Castes Federation, a party he had founded to represent the interests of marginalised communities. He was defeated by Narayan Sadoba Kajrolkar, a Congress candidate and a former aide of Ambedkar, who won by a margin of over 15,000 votes.

Seeking to re-enter the legislative arena, Ambedkar contested a by-election in 1954 from the Bhandara constituency. But, he was unsuccessful again.

These electoral defeats have been a subject of considerable debate and analysis. Leaders from the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) have accused the Congress Party of deliberately orchestrating Ambedkar’s defeats, with Nehru personally campaigning against him.

However, there is very little historical evidence to support claims of a deliberate effort by the Congress to sabotage Ambedkar’s entry into the lower house of parliament. Furthermore, Congress nominated Ambedkar to the Rajya Sabha soon after.

Biographer Dhananjay Keer, in his book Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar: Life & Mission, wrote about the election:

“The Congress Party was the oldest and the best-organised party in the country. Their election preparations had been going on for months together methodically and energetically. Besides, it was a ruling party. Ambedkar could not do much in the direction of organising his party, and owing to his failing health could not go outside Bombay for election propaganda. For the past ten years, he was not in close touch with his organisation, as he had to stay in Delhi as Labour Member and Law Minister. He had no correct idea of the strength and efficiency of his party and that of the Socialist Party.”

(Edited by Majnu Babu).