Published Oct 27, 2025 | 8:00 AM ⚊ Updated Oct 27, 2025 | 8:00 AM

Six works by an international artist displayed at the Durbar Hall Gallery in Kochi, Kerala, as part of the ongoing international exhibition Estranged Geographies, were vandalised.

Synopsis: A row erupted in Kochi over alleged obscenity in a work of art exhibited at Kochi’s Durbar Hall Art Gallery as part of the ongoing international exhibition, Estranged Geographies by Algerian-French artist Hanan Benammar. In India, accusations of obscenity against artworks are rarely about genuine moral concern; they are often politically motivated.

When we fail to critically engage with a work of art, we often end up wielding the sword instead. The recent incident of vandalism in Kochi, Kerala, reflects precisely this kind of intolerance. Ironically, those who defend such destruction sometimes call it an artistic expression while simultaneously denying the very status of the work they attacked, claiming it was not art at all.

In their contradiction lies the very problem: A refusal to confront ideas, a preference for destruction over dialogue, and an attempt to silence expression rather than understand it.

Yes! For the last few days, it was brewing. The row over alleged obscenity in a work of art exhibited at Kochi’s Durbar Hall Art Gallery as part of the ongoing international exhibition, Estranged Geographies. And the contention was over the work by Algerian-French artist Hanan Benammar.

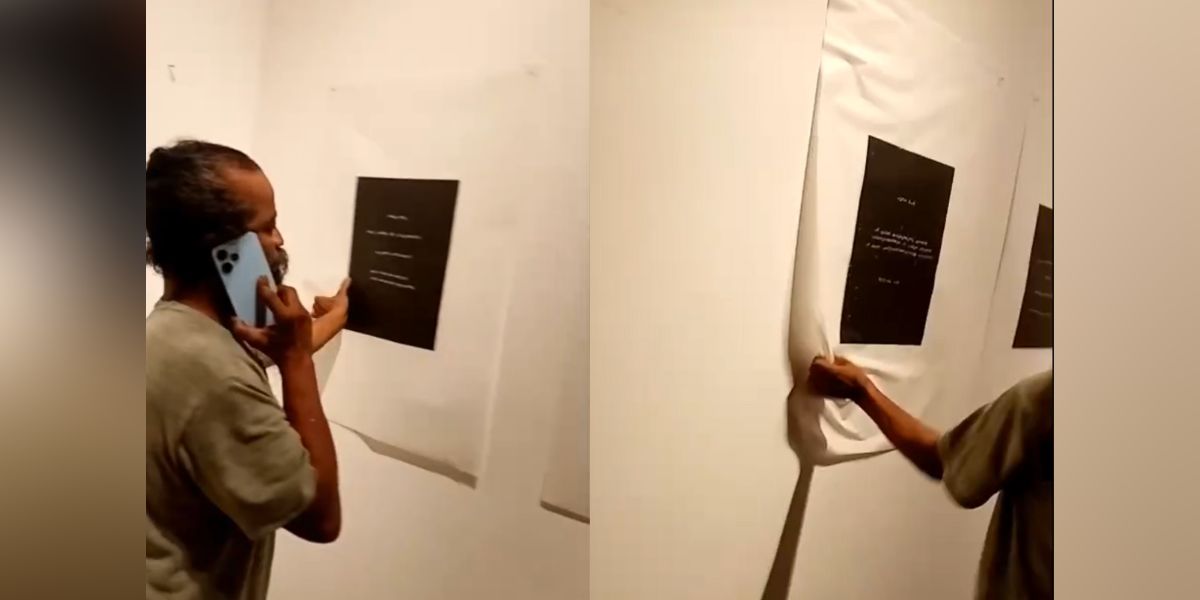

The attackers, who consciously activated the network to apparently livestream the vandalism on social media, claimed the works were “obscene”, echoing a dangerous pattern in which moral outrage becomes a pretext for silencing art. Such acts are not protests; they are assaults on artistic freedom, on public space, and on the very idea of dialogue that sustains culture.

Ironically, a sculpture done in Kerala by one of the attackers portrayed a phallus, but it is still in public view without any moral policing! Vandalism on art is an act of intolerance, and we have many examples in front of us, which even the artists who unleashed the verbal and physical attack know.

In India, accusations of obscenity against artworks are rarely about genuine moral concern; they are often politically motivated. Right-wing groups repeatedly weaponise claims of “cultural purity” and “Hindu values” to police artistic expression and consolidate influence.

Today’s censorship, cloaked in morality, is less a reflection of Indian cultural values than a continuation of colonial and patriarchal frameworks, setting the stage for incidents such as the attacks on MF Husain’s paintings, which provoked nationwide outrage and eventually drove the artist into self-imposed exile.

Under growing pressure and death threats, he went into self-exile in 2006, eventually settling in Qatar, where a museum is set up in his name. However, the attack on Husain impacted the art scene, and galleries became wary of exhibiting works depicting deities in unconventional forms.

We should not forget that Bhupen Khakhar’s works, which depicted homosexuality and nudity, were targeted by right-wing groups in Mumbai, though not vandalised. Contemporary exhibitions in smaller cities featuring nudes or socially critical themes have also faced vandalism or threats, though many incidents went unreported.

The way Hanan Benammar’s works were attacked, however, is rare. The assault on her pieces underscores this ongoing issue, even though the perpetrators claim to be progressive. It reflects how religious, cultural, and political sensitivities have repeatedly targeted artworks in both galleries and public spaces across India.

In 1993, activists from Hindu nationalist groups entered the Lalit Kala Akademi during the National Exhibition of Art and protested against certain works, accusing the artists of immorality and obscenity.

In this broader context, the attack on Hanan Benammar’s work must be seen as a symptom of the same authoritarian impulse that fears critique, especially when voiced by women. Benammar’s art confronts the abusive and misogynistic language that circulates freely on social media.

Much of her work, produced in Norway where she lives, draws from actual threats and insults she received from her estranged partner. She transforms these words into installations, sound pieces, and visual forms, forcing audiences to confront the violence embedded in everyday speech.

The controversial piece, titled Go Eat Your Dad, takes the form of a stencilled print. The words originate from private, threatening, and sexually charged messages sent to Benammar by her former friend in Norway. By presenting the work in Malayalam for an audience in Kerala, she translates private harassment into a local public sphere, transforming personal abuse into a visible critique that exposes mechanisms of male violence and reclaims agency over the words meant to intimidate her.

However, whether the translation changed the context is worth debating. But no one can deny that it was a political act, which is nothing new in the history of art, and hence the vandalism cannot be justified.

All these acts reflect cowardice, ignorance, and intolerance, said Chennai-based artist Vidya Sundar, who described the vandalism by some artists as yet another form of abuse — this time against a woman artist addressing the verbal violence she had endured from toxic men.

“Hanan is a confident and accomplished artist, fully aware of what she is doing, where, and why. She achieved her purpose the moment those wounded egos began barking at her work, while most women artists, silenced by fear or habit, either stayed quiet or sided with the patriarchal voices,” Vidya observed.

Provocative performances are nothing new in the West. Recently premiering her performance Balkan Erotic Epic in Manchester, Serbian conceptual and performance artist Marina Abramović remarked, “We always see pornography in everything, but this is not pornography.”

Featuring around 70 performers, the work unfolds through striking tableaux of exaggerated sexuality – twelve-foot phallic sculptures, dancers baring their bodies, and ritualistic gestures that blur the lines between ecstasy, violence, and spirituality. If it had been performed here, she would likely have received more brickbats than bouquets, for we are often conditioned to oppose what we secretly indulge in through voyeuristic fascination.

Yes, the destruction of a work of art can itself be an artistic expression, as seen in Chinese artist Ai Weiwei’s Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995), a photographic triptych showing the artist holding, dropping, and standing over the shattered remains of a 2,000-year-old urn. Ai had lawfully acquired the urns and broke them deliberately to question notions of cultural value and authority.

The Kochi vandalism, however, was a literal act of breaking into a gallery, removing an artwork, and throwing it to the floor — an entirely different act.

At Estranged Geographies, the vandalism, however, was later reframed in a curatorial gesture. The footage of the attack was incorporated into the exhibition itself. The damaged works remain on the gallery floor as stark evidence of the incident, while a video of the vandalism plays alongside them — transforming an act of destruction into a site of reflection on censorship and artistic resistance to misogynistic aggression.

This attack goes beyond a single artwork; it is a direct assault on the freedom of expression and on the integrity of India’s art institutions, said the organisers.

The exhibition, curated by Anushka Rajendran and Damien Christinger, features artists from France, Norway, Switzerland, and Kerala, aiming to situate regional practices within a global context. While curatorial flaws may exist and should be critically examined, vandalism is not a legitimate form of debate.

Regarding the so-called obscenity allegation, no official complaint has been filed. Concerns could have been raised and addressed through proper channels, yet the issue was instead amplified on social media. Amidst this online attack, the perpetrators appear to have deliberately planned a physical assault, framing it as a “protest”.

This act has, in effect, precluded a meaningful discussion on the merits of the exhibition. Coming at such a prominent platform, the vandalism is seen as a serious embarrassment for Kerala’s art scene, raising urgent questions about intolerance, the safety of public art spaces, and the possible intent of the attackers to create the impression that galleries like Durbar Hall are unsafe for art.

What was the actual target? Akademi or the work of art?

We should keep in mind that Benammar, based in Oslo, is an internationally recognised feminist artist known for her work addressing language, gender, and political activism, and hence this vandalism might have repercussions outside India, according to Akademi Chairperson Murali Cheeroth.

“There has been a concerted effort to create the false impression that we are ignoring the local artists and focusing more on outsiders. With this attack by a group, led by artist Hochimin, who is the beneficiary of a recent art camp organised by us, they want to create the impression that Akademi galleries are vulnerable to such vandalism,” he said.

In recent years, high-profile incidents of art vandalism have highlighted the vulnerability of cultural heritage worldwide. At Florence’s Uffizi Gallery, a visitor damaged a 300-year-old portrait of Ferdinando de’ Medici by Anton Domenico Gabbiani while attempting to mimic the subject’s pose for a selfie, prompting its removal for restoration and stricter visitor rules.

In Verona, tourists shattered a Swarovski-encrusted chair inspired by Van Gogh’s 1888 chair, while in Rotterdam, a child accidentally scratched Mark Rothko’s Grey, Orange on Maroon, No. 8.

In Hamburg, Phoebe Collings-James’ installation referencing Palestine was vandalised when a visitor erased the word “Palestine” with their foot, an act condemned as politically motivated.

Similarly, climate activists have targeted iconic works, including Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, Monet paintings, and the Mona Lisa, to protest environmental inaction; while the activists claim moral justification, no artist has ever supported such destruction. These incidents collectively underscore the persistent threats to artworks from both accidental and deliberate acts, regardless of the cause cited.

Benammar’s art insists that public spaces — whether galleries, streets, or social media — must remain open to dissent, ambiguity, and discomfort. At a time when even censorship in art is increasingly questioned, to destroy a work in the name of decency is not to defend morality; it is to betray it.

What is at stake here is not just one artwork, but the principle that art must be free to challenge the gaze that seeks to control it. Unfortunately, the vandalism drew all attention to a single work, simultaneously pushing all other pieces into darkness.

(Views are personal. Edited by Muhammed Fazil.)