Published Mar 21, 2025 | 3:00 PM ⚊ Updated Mar 21, 2025 | 3:00 PM

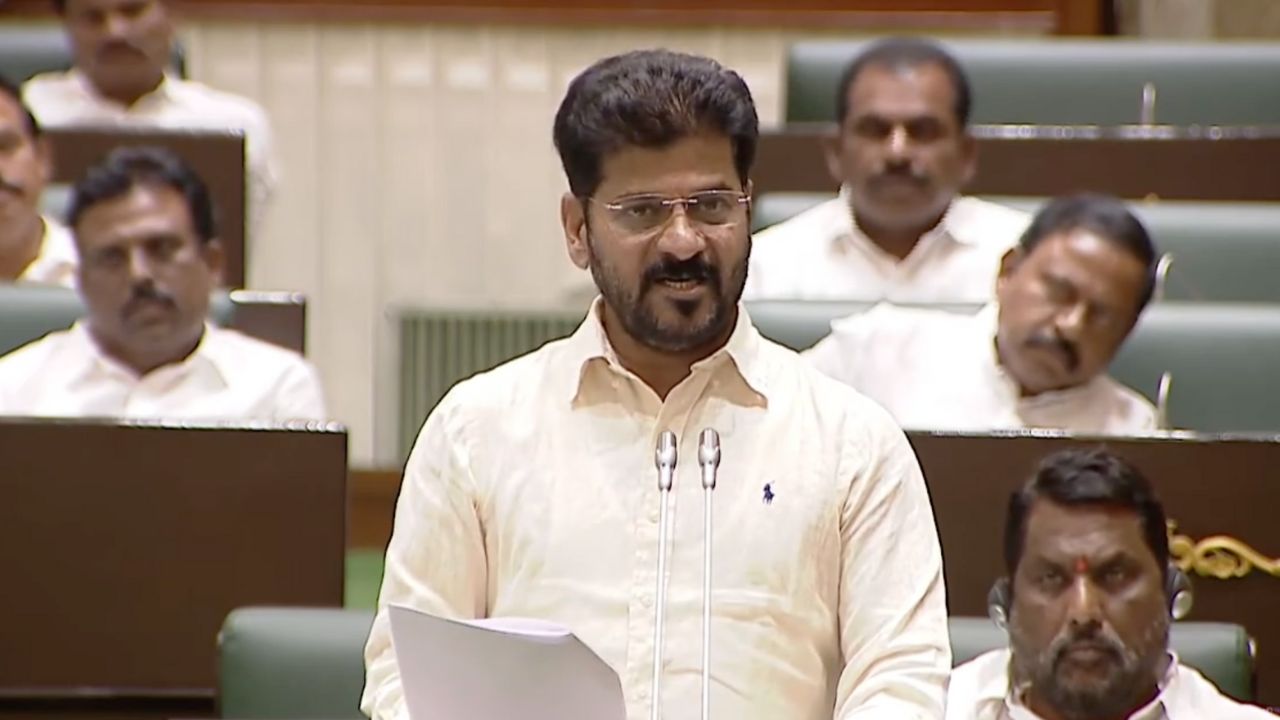

Chief Minister A Revanth Reddy (X)

Synopsis: Telangana Chief Minister A Revanth Reddy’s outburst against a section of journalists was unbecoming of a responsible individual in law-enforcing authority. If the journalists had committed a mistake, their actions certainly warrant investigation and possible punishment — not the sort of street brawl-like threats or actions.

“I will make you suffer, burying in salt… I won’t spare anyone… I’m asking media friends and journalist union leaders. Give me the list of journalists and define ‘journalist’. If anyone on that list makes such a mistake, tell me what punishment you’ll impose. Anyone not on that list is not a journalist. We will treat them as criminals. We’ll answer them in the same coin…I will beat them, strip their masks, parade them naked…”

These words uttered by Telangana Chief Minister A Revanth Reddy on the floor of the state Legislative Assembly have led to widespread discussion, besides sparking a controversy.

Several journalist organisations, including the Editors Guild of India and the Committee to Protect Journalists, along with some individual journalists, condemned the remarks.

Some opined that the context in which these words were uttered should be considered. Yet others stated that the chief minister’s comments were inappropriate, even if directed at people whose actions were not in line with proper journalism, and that such language from a leader was deeply concerning.

In this backdrop, it is necessary to discuss the state of journalism in Telangana, the language of political leadership, and the overall decline in social values.

First, no matter the context in which the chief minister made the remarks, they are not appropriate for someone holding a constitutional office. A person who is supposed to uphold the law and protect it should not threaten to strip people naked, beat them, or bury them.

These words are typically used in street brawls. There are no such punishment (as threatened by Revanth Reddy) in law, and it is inappropriate for someone holding law-enforcing authority to make such threats.

Of course, after all those epithets, Revanth Reddy said he would abide by the law of the land. To speak in one breath of such punishments and in the next to claim that one will follow the law is hypocrisy.

Furthermore, the chief minister’s statement that those who criticise or accuse him should either be journalists or criminals is also problematic.

According to the Constitution, all citizens are equal under the law. Journalists do not have any special privileges, and it is not even right to label all non-journalists as criminals.

For any citizen, whether a journalist or not, the freedom to think, speak, question, and form associations is a natural and fundamental right. These natural rights are protected by the Constitution as fundamental rights.

Among these rights is the freedom of expression, guaranteed equally to all citizens, regardless of caste, creed, region, gender, or age. The freedom of expression, including that of journalists, is a part of this guarantee.

The Constitution also specifies limits to this freedom and allows the state to impose ‘reasonable restrictions’. However, it does not grant the state or the government the authority to remove these rights, strip people naked, beat them, or bury them in salt.

So, what exactly triggered the chief minister’s anger? It is reported that a YouTube channel, Pulse News, interviewed a few individuals who were dissatisfied with government policies and aired their views unfiltered and unedited on the channel and the social media platform X.

In those interviews, abusive language was used against Revanth Reddy and his family. There were also claims that the chief minister would have been killed if he had no security cover. Given that public dissatisfaction with the Congress rule is growing, the speakers might have been genuinely expressing their views.

Based on complaints about the broadcast of these remarks, the police registered a case and arrested the Managing Director and a reporter of Pulse News on 12 March. They were released on bail on 17 March, but the matter has sparked a widespread debate.

Since the controversy began, Opposition leaders and their supporters have stood by the arrested journalists, claiming that the remarks should be viewed as the words of frustrated individuals. That might be true. However, in journalistic tradition, it has been customary to edit out such personal, crude, obscene, and disrespectful remarks before publishing/telecasting.

While there may not be as many checks and balances in electronic media as there are in print media, it is still customary to ensure such comments are not broadcast, even if it means censoring them with a beep sound. But with the rise of social media, no such editing or regulation seems to exist, allowing free expression to go unchecked.

Since Pulse News reporters and management did not take precautions while airing the vile language, their actions certainly warrant investigation and possible punishment. However, if these remarks were broadcast unintentionally or by mistake, they could always be corrected.

However, those involved in the investigation suggest that the channel intentionally aired these comments. It is also claimed that the channel is under the control of the Opposition party, that the interviews took place at the Opposition’s office, and that the people making the remarks were not speaking voluntarily but were tutored and paid by the channel management.

Whether there is any truth to these allegations remains to be seen.

If the remarks were aired by mistake, it constitutes irresponsible journalism. However, if they were deliberately broadcast, it is not journalism at all. If the actions were irresponsible, an apology should be made to the public and the individuals who were insulted, ensuring such a mistake is not repeated.

If they were intentional, the government may take legal action, but care must be taken to ensure that such action doesn’t infringe upon freedom of expression.

This brings us to the question of who can be called a journalist.

The chief minister’s question and his suggestions in this regard are just inappropriate. There are various levels of journalists in the state. The government or journalist organisations can’t compile a comprehensive list of all journalists. Earlier, when only print media existed, there were journalists at village, mandal, district, and state levels, from stringers to reporters to editors.

With the rise of electronic media, many more levels of journalism jobs emerged. And with the advent of social media and advanced technology, thousands of independent journalists have come into existence.

While this explosion of journalism has created vast opportunities for information dissemination, creativity, and expression, it has also created a negative environment with a lack of quality, scrutiny, supervision, and error correction.

Political parties and powerful elites, who have bought mainstream media outlets, have also infiltrated these alternative social media platforms. IT cells with hundreds of employees are spreading false news, accusations, insults, and lies. Abusive language and attacks on opponents, as practiced by politicians, have found their way into social media as well.

In this context, journalism, which was supposed to be the watchdog of society, has turned into a mere lapdog of vested interests. All political parties are responsible for this degeneration. The ongoing debate is a reflection of this decline to gutter journalism.

This debate cannot be resolved by creating lists of journalists alone. There may be half a dozen or more journalist associations, but it is doubtful whether half of all journalists are members of these associations. Therefore, such lists cannot be created by unions.

At the capital level and district level, there are accredited journalists recognised by the government, but they represent only a small fraction of the total journalists. Even if lists of employees from media organisations are collected, they would still be incomplete, as many media organisations label non-journalists as journalists for various purposes.

Additionally, there are hundreds or even thousands of independent journalists in the state who are not employed by any organisation. Therefore, it would be better if the chief minister refrained from attempting to create a list of journalists.

Furthermore, the chief minister should recognise that society is made up of citizens, not just journalists and criminals. Every citizen has the right to think, discuss, and question government policies.

A small group of these citizens, by their profession, bring public opinions and express them through media channels. Expressing opinions is a natural human right, and the Constitution acknowledges and protects this right.

The chief minister must also recognise that political parties, like any other group, may misuse these rights for selfish gains. The government has the authority to take action against such misuse, but care must be taken to ensure that such action doesn’t infringe upon freedom of expression.

The government has the authority to take action against such misuse, but care must be taken to ensure that such action doesn’t violate the freedom of expression.

An ancient Telugu saying goes, “Will we burn the house just because there are rats inside?”

Even now, it is true that the problem proliferated not only with rats, but also bandicoots, but it would be unjust to burn down the house.

(The writer is the editor of an independent, small Telugu monthly journal of society and political economy, running for the past 23 years. Views expressed here are personal. Edited by Majnu Babu).