Published Nov 17, 2025 | 9:00 AM ⚊ Updated Nov 17, 2025 | 11:43 AM

Kerala’s paradise is a mirage – where the hungry are asked to applaud their own starvation, and they are told they have dined.

Synopsis: In a land that boasts of wiping out extreme poverty, hunger still groans beneath painted walls and political slogans. Behind the glitter of statistics, and the staged smiles of ministers and film stars, the stomachs of the poor rumble like muted drums of rebellion. Kerala’s paradise is a mirage – where the hungry are asked to applaud their own starvation, and they are told they have dined.

When the Kerala government declared that the poorest of the poor — or the ‘extremely poor’ — have ceased to exist in the state, only the CPI(M)’s beneficiaries applauded, while the rest of us stood appalled.

We should ask: whose reality has been erased, and to what purpose?

Kerala’s declaration on 1 November that it is “free of the poorest of the poor” is not a triumph of social welfare policy; it is a political performance — a tidy excision of lives without witnesses from the ledger of the state.

Behind this glossy proclamation lies a double tragedy: the continued suffering of hundreds of thousands and the growth of a political order that treats welfare as a tool for patronage rather than a right.

The latter, the bureaucratic capture and localised coercion exercised by an entrenched party apparatus, is nothing less than a political crime. It must be exposed, broken and destroyed for the shared tomorrow of 3.61 crore Malayalis.

When Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan stood before cameras to declare that Kerala has become free of the “poorest of the poor”, it was meant to sound like history in the making. It was framed as the culmination of decades of social progress — a moral triumph of the Left’s welfare state over want and deprivation.

But behind the carefully lit stage and the orchestrated applause lies a more troubling story: a party and government that have mastered the art of betrayal and hoax while forgetting the substance of justice, by converting welfare into spectacle, governance into propaganda and most damningly, data into lies.

“One may smile and smile and be a villain.”

That single line from Shakespeare’s Hamlet captures the grotesque moral distortion at the heart of the CPI(M)-led government’s declaration. A smiling stage, a polished script, and a photographable moment do not do justice.

The state’s official mission may record 64,006 families as those who were in “extreme poverty” and claim to have rescued them through micro-plans and interventions, but the deeper, persistent harms – malnutrition in tribal hamlets, unpaid and delayed pensioners and millions who remain listed under central poverty schemes – tell a different story. (1)

Kerala has the lowest level of multidimensional poverty as per the NITI Aayog report. The Athidaridrya Nirmarjana Project was started to identify those suffering from extreme poverty, currently outside the support system, and to help them come out of the experience of extreme poverty within five years. (2)

How does the government turn urgent social need into a headline and then declare victory? The method is bureaucratic, technical and crucially, political.

The first is by defining the problems narrowly and administratively. Kerala’s Extreme Poverty Eradication Project (EPEP) used a set of local stress indicators to identify 64,006 families for targeted action. But when the measure of success becomes the administrative “closing” of a file rather than sustained, audited improvements in nutrition, income and living conditions, success can be certified on paper even when the ground becomes precarious.

The EPEP page itself states the identification and micro-planning processes; it does not, however, make immediate claims about long-term income security for those families. (3) The identification was through a process of community participation led by local bodies and supported by the ASHAs, Anganwadi workers, Kudumbashree units, residential associations, etc.

As many as 1,03,099 people (64,006 families) were found in 1,032 local institutions in the state. The families were identified based on stress factors such as food, health, income and housing.

Second, by repackaging selective statistics to subsume inconvenient measures. NITI Aayog’s Multi-Dimensional Poverty Index (MPI) places Kerala at the very low end of deprivation nationally — a remarkable achievement that reflects decades of investment in health and education. But low aggregate MPI does not erase pockets of concentrated deprivation.

To conflate the two is to use a legitimately good statistic as a deflection from ongoing structural failures. When the central MPI shows Kerala’s MPI at around 0.55 percent, that headlines invite celebration – and creates a convenient cover under which the state’s specific failures can be brushed aside. (4)

It is one of the great ironies of modern Kerala that the communist parties, which came to power riding on the moral and social energies of the lower-caste enlightenment movement, later claimed as their own what the avarna militant struggles had already achieved.

A statue of Ayyankali.

Of all the myths the Left has woven around itself, none is more enduring – or more deceptive – than the claim that Kerala’s achievements in education and health are unique contributions of its welfare policies.

Long before the red flag fluttered in the streets, and health aglow – compelling every later government, Left or Right, to follow its light — Kerala had already been reshaped by a militant Avarna Enlightenment, led by Narayana Guru, Ayyankali, Sahodaran Ayyappan, and hundreds of agitators from oppressed castes.

They fought not class wars but for human dignity, for the right to wear clothes, the right to read and write, to walk on public roads, to eat with others and to name themselves as equals.

The Avarna Enlightenment was the battle to recapture the ‘human existence’ stolen and trampled by the minority upper-castes. This was an open war between the 85 percent avarnas on the one side and the 15 percent savarnas on the other.

Sahodaran Ayyappan.

The only genuine “contribution’ of the communist party in Kerala was to defuse a living caste war by misdirecting it into a theoretical class war, in a land where no true class existed, only castes masquerading as classes.

It was these avarna fighters who pried open the sanatana brahminical racist order, which had for centuries treated education and health as caste privileges. The first agrarian strike by Ayyankali in 1907 was not waged for land or wages but for education – for the revolutionary right of Dalit children to enter a school. It was this avarna insurgency, not any Marxist class awakening, that laid the welfare foundation of modern Kerala.

By the time the first communist government took office in 1957, literacy in Travancore had already crossed 60%. Missionary and lower-caste run schools dotted the landscape, and public health infrastructure, begun by the Travancore and Cochin administrations under pressure from avarna movements, had already achieved milestones in sanitation and maternal health.

The savarna Marxists inherited a society already mobilised by the oppressed castes of Kerala; it did not create one.

The CPI(M)’s narrative that it built Kerala’s “welfare model” rests on deliberate lies and falsehoods. The truth is that Kerala’s modernity began when the avarna castes wrested from the savarnas the right to knowledge. The Left merely institutionalised what was already socially inevitable. To equate continuation with creation is a distortion.

If anything, post-1957, the Left substituted the moral vocabulary of equality with the sterile jargon of “class struggle”. The result was not liberation but a change of metaphor: the Nair-Nazrani became the bourgeois, the avarna the proletariat. The structure of inequality – ritual, social and linguistic remained untouched.

It was with the quiet substitution of flesh-and-blood caste with paper-and-ink class that the real was displaced by the imaginary. It allowed the CPI(M) to claim the Avarna Enlightenment mantle while deflecting attention from caste, which remained the fundamental line of division in Kerala’s lived reality.

The savarna Marxist imagination universalised class and invisibilised caste, turning a concrete struggle for human dignity into an abstract economic drama.

Even the much-wanted investments in education and healthcare were not born of communist magnanimity but of political compulsion. Once the avarna public had tasted self-respect through schooling and organisation, no government, Left or Right, could reverse that tide without inviting revolt.

The Left merely administered what the Avarna Enlightenment had made irreversible. It was the outcome of countless blood-letting struggles by the avarnas – battles fought not for abstract ideals but for the right to exist, to learn, to see and to be seen. When the CPI(M) claims credit for them, it commits not only a historical theft but a moral one – erasing the avarna men and women who built the institutions with sweat and sacrifice.

The Avarna Enlightenment was, at its core, ‘existential’ and ‘humanist’. It conceived equality not as redistribution of resources but as the recognition of the avarna life as ‘dignified human existence’, the assertion of the shared personhood in a society that denied them humanity. Its leaders enjoined their followers to be enlightened through education and to be strong and fearless through organisation.

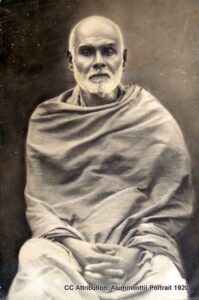

Sree Narayana Guru.

At the height of the Vaikom agitation in 1925, Narayana Guru said that “those who believe that touching another human being defiles them should not be allowed to move about freely and calmly”. (5) When Gandhi came to know this, he was provoked to write an article in Young India that, “Narayana Guru, the spiritual leader of Ezhavas in Kerala, was publicly inciting violence…” (6)

The CPI(M) replaced the caste conflict with a dogmatic rhetoric of class contradiction, which, in practice, made the struggle against caste insignificant. For all its talk of revolution, the party never inducted a Dalit into its polit bureau. Its organisational and intellectual life always remained dominated by ‘a chunk of Brahmin boys’, as Ambedkar wryly observed – men who spoke in the name of the poor while ensuring that Brahmin – kshatriya – bania raj remained intact.

As a result, Kerala today has a paradoxical modernity: high literacy, yet deep upper-caste supremacism; excellent health indices, yet rigid social stratification.

In Kerala, the communist project became an act of diffusion, extinguishing the fiery struggles for freedom and equality and replacing them with a network of political mafia.

Even the welfare schemes the CPI(M) celebrates – from land reforms to literacy campaigns – were, in essence, state responses to earlier militant demands. The smiling face of Kerala’s Left hides a mind that knows its inheritance was stolen, not earned.

To reclaim the true anti-caste legacy necessarily entails dismantling the ‘foundational myths’ constructed by the communist party and perpetuated by Kerala’s ‘cultural Left underworld’.

The foundations of Kerala’s human development were laid by the Avarna Enlightenment, not by party ideologues. The communists arrived after the battle was partially won, and turned it into bureaucratic governance. If Kerala is exceptional, it is because its oppressed refused to wait for the state. In truth, the light that illuminates Kerala’s schools, hospitals and roads is not Marxist red but the hard-earned glow of Avarna enlightenment.

Central food security rosters show that Kerala still has around 5.9 lakh Antyodaya (AAY) yellow-card households – a figure repeatedly cited in parliamentary and media debates. If such large numbers remain on the Union government’s “poorest” lists, the state’s claim to have entirely “eradicated” extreme poverty looks, at best, partial, and at worst, a reclassification exercise.

The Opposition’s demand for the release of raw survey data and methodology is not noise but a necessity. (7)

Houses, inaugurated on cameras, one-time food-kits and episodic healthcare camps do not substitute for the steady, institutional mechanisms that prevent starvation and chronic deprivation: uninterrupted pensions, dependable primary healthcare outreach, child nutrition services with continuous monitoring, and land and livelihood guarantees for tribal communities need to be ensured. When those institutions are weak, a government can give the impression of action without resolving the underlying insecurity.

No single issue tests the credibility of the “extreme poverty free” claim more than Attapadi in Palakkad. The National Institute of Nutrition (NIN) and independent researchers have repeatedly documented a crisis of under-nutrition and child mortality among the adivasi communities of Attapadi – a crisis linked not to fate but to dispossession, ecological marginalisation and systemic failure of outreach.

The NIN Attapadi report (8) explicitly documents high rates of malnutrition and points to failures in restoring access to land and forest resources and appropriate health and nutrition interventions. A government that declares the end of extreme poverty while Attapadi’s children remain malnourished is guilty of a particular kind of cruelty: the cruelty of spectacle that hides selective care. (9)

The second betrayal is political. The CPI(M), which governed Kerala for decades on the currency of mass mobilisation, land reforms and public goods, now faces credible charges of converting its social base into a managed clientele. Where mobilisation once meant empowerment, the patterns visible today – from allotment lists filtered through party channels to the capture of cooperatives and local procurement circuits – indicate a shift from movement to mafia.

The empirical evidence of capture is multi-sourced: investigative reports, civil society complaints, and the repeated public demand for the disclosure of methodologies behind EPEP.

When procurement, beneficiary lists and housing allotments are functionally opaque, favouritism and exclusion become structurally possible. When whistleblowers and local activists are silenced or sidelined, the political machinery is protected. The result is a party that secures loyalty through access and dependence, rather than winning consent through accountable programmes.

That is why the charge of a “political mafia” resonates – not because it imputes criminality to every cadre, but because it names a system in which access to the essentials of life is mediated by party networks. This mediation converts rights into privileges and reduces citizens to clients.

Let’s name the moral claim plainly: Kerala’s public wealth — its hospitals, schools, panchayats and co-operatives – belongs to 3.61 crore Malayalis. When public goods become instruments of political rent, the people’s future is stolen. That is the proper register of outrage.

If the CPI(M)-led government and Chief Minister Vijayan are sincere about the welfare legacy they inherit, they must meet three demands: open their data; publish the EPEP methodology; and commit to binding social audits for every rescued family, with judicially enforceable follow-ups.

Only then can a claim of eradication be judged on evidence rather than ceremony.

Kerala’s achievements in literacy, health and human development are real and worth defending. They are the reason the state’s errors matter so much: because a polity with such resources has no excuse for cosmetic governance. A welfare state that prefers image to institution will ultimately betray the very social contract that built its credibility.

The antidote is not rhetorical fury alone; it is organised, lawful, evidence-based pressure that reconstructs the instruments of justice. Publish the lists. Audit the claims. Rebuild the institutions. Let the final verdict rest on sustained improvement in nutrition, housing and dignity – not on photographed announcements but on the invisible hunger that cameras never visit.

Above all, let the people reclaim the language of their claim, the uncompromised future of 3.61 crore Malayalis — a future that cannot be declared away on a podium but must be earned, and entrusted to institutions that serve all, not just the few who clap the loudest.

India’s headline progress — falling poverty rates, booming GDP numbers and glossy development indices mask a cruel truth: poverty in India is not merely an economic condition, it is a caste condition. Multiple international and intergovernmental studies make the link explicit: Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes remain far more likely to be poor, malnourished, excluded from services and economically marginalised than upper-caste groups. (10)

Oxfam’s study on inequality has shown how India’s wealth is highly concentrated at the top, while the poor receive almost none of the gains. Oxfam India’s inequality study and its 2022 discrimination working paper document how social institutions – caste foremost among them – shape access to decent jobs, credit and safe work.

Occupational segregation persists: sanitation workers, leather industry labourers and rag-pickers remain disproportionately Dalit and Adivasi, trapped in low-pay, hazardous work with minimal social security. In practical terms, the “poor” in India and Kerala are most often those whose caste consigns them to the margins. (11)

Global institutions echo this diagnosis. The World Bank’s focused studies on poverty and social exclusion note that Dalits and tribal communities experience systematically worse outcomes across health, education and livelihoods; they are over-represented among the multidimensionally poor and underrepresented in assets and formal employment.

The UN and allied observers have repeatedly highlighted that almost one-third of Dalits remain trapped in multidimensional poverty despite national averages improving – a stark reminder that aggregate progress leaves caste based deprivation intact.

The consequences are visible in everyday life. Peer-reviewed nutritional studies show that lower-caste households consume fewer fruits and vegetables and have poorer diet quality even after controlling for income and education, indicating that caste-based discrimination and deprivation shape health outcomes directly.

UNICEF and other agencies similarly document that Dalit girls face exclusion from schools and higher dropout rates, which reinforces intergenerational poverty. In short, the hungry are disproportionately Dalit and Adivasi; the secure and comfortable are disproportionately upper-caste. (12)

If India’s anti-poverty strategies ignore caste, they will misfire: universal subsidies and market-first growth policies will continue to be captured by the already privileged. International reports make clear the remedy: affirmative public provisioning, caste-disaggregated data, targeted anti-discrimination enforcement, labour protections for caste-segregated trades, and sustained investment in nutrition and schooling for Dalits and Tribal communities. (13)

The brutal killing of Madhu, a 27-year-old Adivasi man from Attapadi, accused of stealing a little rice and food, stripped bare the myth of Kerala’s progressive egalitarianism.

Tribal youth Madhu, just before the lynching. A picture circulated then by the attackers claiming they nabbed a thief. It was removed from their social media pages later

On 22 February 2018, a group of local men, mostly settlers and land grabbers who had long exposed Adivasis, accused him of stealing food items from a shop. Instead of handing him over to the police, they caught him, tied his hands, mocked him and brutally beat him.

Madhu’s frail body – haunted by hunger, poverty, and social isolation – was not just beaten to death by a mob; it was lynched by centuries of caste apartheid and structural neglect. His death was the inevitable outcome of a society that cloaks its hypocrisy in the rhetoric of development and literacy.

Madhu’s story echoes Akira Kurosawa’s Dodes’ka-den — a haunting portrayal of a destitute boy who lives in an imaginary world, amid the wreckage of a slum. In one of the film’s unforgettable scenes, a starving boy is beaten for stealing a piece of bread.

Kurosawa, through this boy, exposes a civilisation that punishes the poor for the ills of its own inequality. Madhu’s death replays that same moral tragedy – where the hungry are criminalised, and the privileged find moral satisfaction in punishment.

Kerala has traditionally been hailed as a model of human development, celebrated for its high literacy, social welfare, and egalitarian ethos. Yet, the tribal hamlets of Attapadi remain spaces of abandonment and slow starvation, where hunger, malnutrition, and displacement have persisted for decades.

The glittering narrative of the “Kerala Model” fades here, revealing a darker truth – that development in the state has often meant the exclusion and dispossession of its original inhabitants: the Adivasis.

In short, to present poverty in India as merely an economic problem is a grave intellectual error. Economics, in its classical sense, is a science of wealth, not a science of apartheid. It measures poverty through income, consumption, and productivity, but remains blind to the social architecture that determines who is condemned to poverty in the first place. In India and Kerala, that architecture is caste.

Caste predates capitalism and continues to govern access to land, education, food and dignity. It determines who performs degrading labour, who remains landless, who suffers chronic malnutrition, and whose children die before their first birthday. Poverty in India, therefore, is not a mere lack of resources – it is a hereditary condition produced and maintained by a re-layed system of inequality and social exclusion.

What India and Kerala urgently need is a new science of caste-based poverty – a framework that studies deprivation not through market indicators but through the social logic of exclusion and humiliation. This new approach must ask: who eats last, who serves, who cleans, who dies first, who lives less, who speaks less, who dreams less – and why?

It must bring sociology, history and political philosophy into dialogue with economics, dismantling the illusion that poverty is merely material.

Until poverty is understood — not as a failure of the economy but as a product of the caste system — every welfare measure will remain cosmetic. True progress demands not charity or food-kit, but a radical undoing of social order that breeds poverty as its natural consequence.

In a land that boasts of wiping out extreme poverty, hunger still groans beneath painted walls and political slogans. Behind the glitter of statistics, and the staged smiles of ministers and film stars, the stomachs of the poor rumble like muted drums of rebellion. Kerala’s paradise is a mirage – where the hungry are asked to applaud their own starvation, and they are told they have dined.

The conjurers of prosperity say Kerala has conquered poverty. That the last torn belly has been stitched, the last empty pot filled, the last wound of hunger healed. The wizards of welfare proclaim with fanfare that this is now a paradise, whose statistics shine brighter than the sun. In Kerala, the howls of hunger have ended forever – not because stomachs are full, but because the numbers have tamed poverty; it seems to have been eradicated by statistics, not by food.

Beyond the magic of making data into falsehoods lies another music: the slow, muffled wails of hunger, through the rusted slums, through Laksham Veedu colonies where hope has been rationed to death.

References:

(Views are personal. Edited by Majnu Babu).