Published Jul 09, 2025 | 12:00 AM ⚊ Updated Jul 18, 2025 | 11:21 AM

For many, verifying their right to vote has become a race against time and red tape.

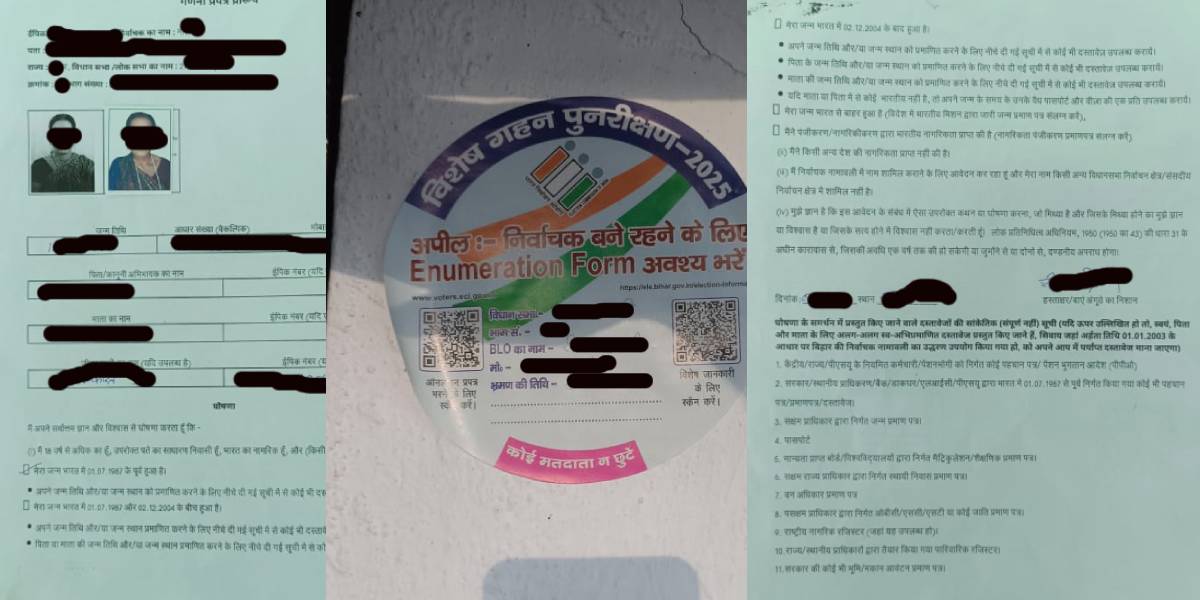

Synopsis: The Election Commission’s Special Intensive Revision of electoral rolls in Bihar has put the state’s majority population in a fix. They are now chasing documents for their Constitutional Right to Vote.

It’s a sweltering afternoon in Bihar’s Sitamarhi district on Monday, 7 July. Sugiya Devi (name changed) wearily treaded the dusty lanes of Kharka Basant panchayat in the Bajpatti constituency, her saree pallu tightly drawn over her head to shield herself from the merciless sun.

Near the village Durga temple, she joined a small queue outside a local internet café, one of the few digital lifelines in the area. Several villagers were already there, holding voter ID cards or documents, hoping to make sense of the new rules under the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) drive of the Election Commission.

Once her turn came, Sugiya asked the café owner for “her papers for voting

He searched through the folders and pulled out a photocopied voter list from 2003, back when the area fell under the now non-existent Pupri constituency. “Which ward?” he asked.

“Thirteen,” she replied, and gave her name. He printed out three pages, her proof of having been a voter before 2003.

He has been printing these out for many villagers over the past few days. People attached them to the enumeration forms being distributed by Booth Level Officers (BLOs). If their names, or their parents’ names, appeared in the old rolls, it helped validate their claim to vote.

When Sugiya returned to her locality, a BLO was already filling out forms for the residents. For her, the process was smooth. She was a voter before 2003, and her name in the old list would suffice. But when she tried to register her son and daughter-in-law, both working as migrant labourers in distant cities, the BLO looked up from the form he was filling.

“They’ll need other documents,” he said, listing 11 acceptable proofs.

For those who became voters after 2003, a preferred document was the 10th-grade board certificate, where a parent’s name was typically mentioned. But Sugiya’s son and daughter-in-law never cleared high school.

She rushed inside and returned with residential and caste certificates issued in 2018, documents they had used while applying for an Aadhaar card. But the BLO was not impressed. “They need to be dated after 2023,” he told her.

Sugiya was visibly worried. “What can I do now?”

The BLO tried to help. “I will file the form now. But please get the updated residential certificate by 25 July,” he said, making a note.

Sugiya hurried back to the same café. The owner, familiar with the process, filled out the online form for residential certificates on her behalf. “Come back on 18 July,” he told her. “You’ll need to go to the block office. An official there will sign it.”

“This is unusual,” the café owner said. “Normally, there’s a rush for residential certificates during school or college admissions. But now, it’s people wanting to vote.”

As Bihar prepares for its upcoming assembly elections, the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of the electoral rolls has become an administrative headache — and a personal crisis for millions. For many, verifying their right to vote has become a race against time and red tape.

The Election Commission’s list of acceptable documents read like an exclusive club — one that doesn’t seem designed for the average citizen. Despite being widely used for government services, identity cards like Aadhaar, PAN, driving licence, MNREGA job cards, and even Ayushman Bharat cards are not accepted for voter verification under the SIR.

Instead, the following are considered valid:

In total, around 2.93 crore people across Bihar must now scramble to prove they are citizens, eligible to vote.

But here’s the catch: many of these documents are either out of reach or irrelevant for the vast majority of Bihar’s population.

Take government-issued identity or pension orders, for instance. Bihar has roughly 20 to 30 lakh people who are government employees or pensioners. That leaves over 2.6 crore people outside the purview of this option.

Some, like students preparing for government jobs, are better placed. They often renew their caste and residence certificates regularly for entrance exams and job applications. But that’s still just a fraction. For the rest — daily wage workers, migrant labourers, homemakers, elderly villagers — these documents may never have been issued or are hopelessly outdated.

When residents of Kishanganj district began queuing up at government offices to get residential certificates, the state’s Deputy Chief Minister, Samrat Chaudhary, publicly mocked them on religious lines while ignoring the struggles of lakhs of voters.

Land and house allotment certificates offer little relief. Most property in rural Bihar is ancestral and held in the names of elders, not the new generation of voters who came of age after 2003. Even those who have land titles fear that presenting them might disqualify them from food ration entitlements, based on the belief that owning even a few decimals of land makes them too “rich” to need welfare.

Then there’s the passport — a symbol of aspiration, but also of privilege. In Bihar, where millions struggle to feed their families and survive off seasonal migration, international travel is a distant dream. The number of passport holders is vanishingly small compared to other states.

If the system expects everyone in Bihar to furnish matriculation certificates, it is forgetting a reality: for many, school is where you show up for a few years, then drop out to support your family. Education, for a large section of Bihar’s population, ends long before a Class 10 certificate is ever earned.

So, what about birth certificates? You’d think that’s basic — but even that is riddled with complications.

Take the case of this correspondent. I have a birth certificate issued by a block-level officer in 2014 — handwritten, stamped, and official. But when I showed it to the BLO verifying voter details, it was summarily rejected.

“This won’t work, it’s handwritten, and it’s from 2014,” I was told. Ironically, the very government that issued the document is now unwilling to accept it.

I am not alone. Thousands of people across Bihar, especially in rural areas, have made such certificates over the years for official paperwork, Aadhaar, ration cards, and school admissions. Yet many of those are now deemed invalid under the SIR process, pushing people into a cycle of re-application, lost time, and mounting frustration.

Other documents? They’re even less accessible.

Forest rights certificates? Bihar has relatively few forests, and hardly any forest officers are accessible to the average villager. NRC documents? Those exist in theory, but are irrelevant to almost everyone in Bihar except in areas bordering Assam, and even there, their legal standing is precarious.

And then comes the unspoken cost of this document rush.

To get your certificate approved, it’s not just about standing in line; it’s also about secretly slipping currency notes under the table. For many, the price of voting rights isn’t just paperwork; it’s a bribe, a bus fare, and a day’s wage lost.

Meanwhile, the BLOs — the frontline of this massive exercise — are just as overwhelmed. They juggle papers and online portals, pleading with villagers to somehow get “acceptable documents.” But they also carry the emotional burden. These are not faceless officials. They are neighbours, kin, and friends. If someone from their tola or panchayat is struck off the voter list, the blame will land on their shoulders, not on any higher authority.

“They’ll curse me, not the system,” one BLO told South First. “We’ve lived through enough curses.”

Every day, local newspapers and even the national newspaper based out of another part of the country carry heartbreaking stories of ordinary people, farm workers, domestic labourers, elderly widows, being told they are no longer citizens in their own country.

Their crime? Failing to produce the “right” document from a list that feels more like a bureaucratic puzzle than a democratic safeguard. And while they queue in the scorching sun, visiting government offices for the third or fourth time, spokespersons of the ruling establishment sit in air-conditioned studios, claiming everything is “routine” and “smooth”.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).