Published Jun 03, 2025 | 12:00 PM ⚊ Updated Jun 03, 2025 | 12:00 PM

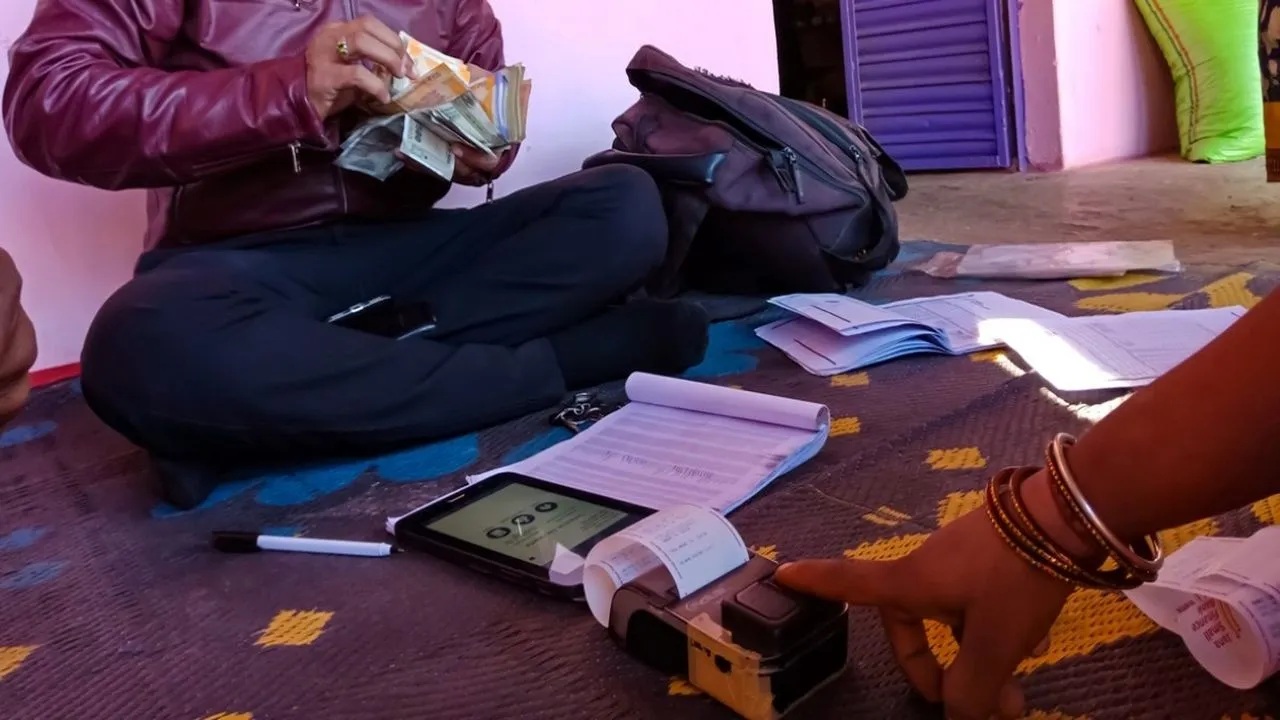

Institutions target women, particularly those from low-income groups, and use strong-arm tactics to collect payments.

Synopsis: To rein in unscrupulous financial services, Kerala must implement stringent regulatory measures, including licensing requirements, interest rate caps, and regular audits. It’s crucial to recognise the failures of neoliberal policies and adopt alternative models like cooperative banking and social finance initiatives to provide equitable access to credit. By prioritising people over profit, Kerala can protect its vulnerable populations and foster a more inclusive economy.

Exploitation, fraud, and coercion, targeting vulnerable individuals from low-income backgrounds, plague Kerala’s microfinance sector. Unscrupulous institutions lure people into availing loans at exorbitant interest rates, often using manipulated or forged documents. Representatives from poor socio-economic backgrounds are recruited to canvass clients, perpetuating the cycle of debt.

A chilling example is Ezhamkulam, Pathanamthitta-resident Latha TJ’s experience. Her neighbours, Divya and Reju Kumar, approached her with a tale of financial hardship, asking her to pledge her Aadhaar card to secure a loan of ₹1 lakh from a popular non-banking financial company. Latha trusted them, unaware that they had already taken loans using other people’s Aadhaar cards.

Divya and Reju Kumar were later found dead, leaving Latha and 11 others responsible for repaying the loans. The microfinance institution (MFI)’s staff now demand weekly interest payments, threatening and intimidating those who cannot pay.

According to sources, Reju Kumar and Divya died by suicide following harassment by the loan recovery staff of the bank for defaulting on payments. The incident was reported on 12 September 2024.

Omanakuttan of Ezhamkulam panchayat and his wife, Amitha, also took more than ₹2 lakh from three MFIs in Pattazhy, at the prodding of Divya and Reju Kumar.

“We became sympathetic to their pleas and took the loans. Now we have to pay ₹3,000 per week, and we don’t have any means to pay back the money,” Omanakuttan said.

The MFI employees regularly follow up on the payment. Reena, a resident of Ezhamkulam, took ₹70,000 from an MFI, and for the past six months, she has been remitting ₹800 a week, which will continue till the beginning of 2026. Her only revenue is from the MGNREGS.

These cases highlight the ugly truth of microfinance fraud in Kerala. Institutions target women, particularly those from low-income groups, and use strong-arm tactics to collect payments. According to banking sector sources, these institutions only lend to women, who are often without legal backup, leaving victims vulnerable to exploitation.

Shafeek Abufaisy of Punalur narrated his experience with MFIs. Despite paying almost all the interest and principal, he has been facing relentless calls and threats.

Shafeek, who had been working in the Middle East, availed loans from three institutions after relocating to Kerala. The man said he had almost paid the interest and the capital. Even if he defaulted on a single weekly installment, the company staff would call him with threats. Shafeek said there were also incidents of the staff trying to physically assault him.

Professor Vinoj Abraham of the Center for Development Studies attributed these issues to non-banking financial services institutions lending without collateral security. He emphasised the need for effective regulation and adherence to the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) guidelines.

He said that certain non-banking financial services institutions may be lending loans to the clients, and Divya’s case could be linked to the bank staff canvassing clients to meet their monthly target.

“This may also be the problem when private financial institutions, instead of nationalised banks, are lending money. In the case of the former, they may charge excessive interest rates. These financing institutions are lending money without any collateral security, so that people will be interested in borrowing money. When the clients are not paying the interest rates, they may use force,” he added.

Abraham, however, said that there are specific RBI guidelines on lending and fixing interest rates. If any private financial institution flouted the rules, legal action could be initiated against it.

However, it’s crucial to acknowledge that MFIs fill a critical credit gap for poor women and low-income households lacking access to traditional banking services. While concerns around exploitative interest rates and financial literacy are valid, microfinance provides a necessary social safety net.

According to banking sector sources, financial institutions will provide loans to women, especially if they form a group. The MFIs will not give money to men. Since they are working solely without any legal backup, they cannot take any legal action against the people who are not remitting the interest or payment. The only way is to threaten the people with goons, which will mostly only work against women from a poor socioeconomic background.

To address these complexities, Kerala requires:

1. Effective regulation of MFIs.

2. Financial literacy programmes.

3. Affordable credit alternatives.

According to Christabell PJ, an Associate Professor of Economics at the University of Kerala, the proliferation of MFIs in Kerala, despite their questionable business practices, can be attributed to the state’s unique socioeconomic landscape.

“Rather than viewing MFIs as exploitative, I believe they fill a critical credit gap for poor women and low-income households, who lack access to traditional banking services. The high interest rates associated with MFIs are, in part, justified by the high transaction costs involved. Furthermore, Kerala’s financial exclusion, poverty, and unemployment have created a demand for alternative credit sources,” she observed.

“While concerns around exploitative interest rates, over-indebtedness, and lack of financial literacy are valid, I argue that MFIs provide a necessary social safety net. Effective regulation, financial literacy programmes, and affordable credit alternatives are essential to ensuring responsible financial practices. By acknowledging the complexities of Kerala’s financial ecosystem, we can develop solutions that balance the needs of vulnerable populations with the need for sustainable financial practices,” Christabell said.

Christabell added that the unchecked proliferation of unscrupulous financial institutions in Kerala will have catastrophic consequences on the state’s economy, particularly affecting female-headed households, who are the backbone of Kerala’s economy.

“As these women manage household finances, educate children, build and maintain homes, and fulfill social obligations like marriages and funerals, over-indebtedness will cripple their ability to sustain their families,” she pointed out.

“The ripple effect will be devastating, leading to reduced consumption and savings, increased poverty, decreased investment in human development, and social unrest. Kerala’s unique economic fabric, woven around its strong social networks and community ties, will be irreparably damaged,” she said.

“Urgent regulation of microfinance institutions, promotion of financial literacy, and provision of affordable credit alternatives are essential to prevent this impending crisis and safeguard the economic well-being of Kerala’s most vulnerable populations,” she opined.

She said the proliferation of unscrupulous financial services in Kerala is a direct consequence of neoliberal economic policies that prioritise profit over people. “Institutions like Kudumbashree initiated with noble intentions and are following the same, even after 25 years of its formation,” she added.

“But the idea has been hijacked by private MFIs employing exploitative tactics to capture the market. The emphasis on deregulation and free market principles has created an environment where profit supersedes social welfare, leading to increased income inequality, decreased government oversight, and financial instability,” Christabell further stated.

To rein in these unscrupulous services, the state must implement stringent regulatory measures, including licensing requirements, interest rate caps, and regular audits. It’s crucial to recognise the failures of neoliberal policies and adopt alternative models like cooperative banking and social finance initiatives to provide equitable access to credit. By prioritising people over profit, Kerala can protect its vulnerable populations and foster a more inclusive economy.

MFIs are of different types. There are those supported by governments like Kudumbasree, promoted by Civil Society Organisations (CSOs), and for-profit ones, which tend to be highly extractive.

Praveena Kodoth, Professor of Economics at the Centre for Development Studies, said that in the first case, they are usually motivated by poverty alleviation, though whether it is effective may differ.

“This format gives access to subsidised loans as governments can absorb the costs, but it may still lead to the turnover of loans from multiple sources. We do not know how long-standing their success with microenterprises is,” she pointed out.

“In the second case, CSOs have a stake in the success of Self-Help Groups (SHGs) and are likely to provide handholding to this end. However, services are a cost therefore, interest rates are likely to be higher. The successful instances of CSOs in Alappuzha and Wayanad have innovated models of microenterprise and political empowerment of women,” Praveena added.

She pointed out that it is the third type (for-profit) that is often dubious. “They use the existing networks to form groups and give immediate and easy access to loans, but are very harsh in recovery. They do not rely on peer pressure or on the composition of groups through trust to ensure recovery. Their staff are also under severe pressure to ensure recovery at the cost of their salaries,” she added.

“The third type also includes fly-by-night operators who seek to make quick profits, as the model may not be sustainable in the long run. They evade scrutiny because they employ local people as staff and threaten people using misinformation. Members are typically women in distress, and they may not be aware of the legalities. They borrow from other sources, including moneylenders, to repay. As is usually the case with unscrupulous creditors, they issue threats, so the women fear going to the police. They end up in huge debt. The dubious ones make quick money and vanish,” she pointed out.

According to the experts, the RBI should formulate specific guidelines for the functioning of MFIs and ensure that the other non-banking finance companies strictly adhere to the existing guidelines.

Currently, some institutions are working without any specific guidelines. Since the lenders are working without adhering to norms and with one-sided agreements, the victims cannot approach a court or police station to challenge the transgressions of these financial institutions.

A study by the Centre for Socio-economic & Environmental Studies (CSES) revealed that a large majority of the sample households experienced a reduction in income due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Nearly one-fifth reported a complete loss of income.

The study also pointed out that the reduced income in the lower-middle-class households increased the tendency to borrow.

The average additional debt burden created by the rural poor households since the lockdown is ₹40,1667. In this scenario, a relook at the options available at the local level to enhance household income is necessary.

The local government should devise innovative schemes to boost employment and entrepreneurship, in partnership with Kudumbashree and co-operative institutions. Efforts should also be made to learn from and adopt successful models to promote the local economy.

Kudumbashree served as a crisis-management mechanism during the crisis. However, 30 percent of the rural poor households are still outside the Kudumbashree network, depriving them of an easily accessible source of credit and other benefits, making them more prone to a financial shock.

This disparity was reflected in the credit source choices of rural poor households with and without Kudumbashree membership. The study noted high reliance on moneylenders, friends, and relatives among families who do not have Kudumbashree membership compared to those with membership.

Nalini Balan, Chairperson of the Community Development Society of the Kudumbasreee in Kottayam Municipality, said that they are giving up to ₹1 lakh to self-help groups of five women at an interest rate of seven percent.

“We can successfully manage the process without any complaints. Regarding money provided from non-banking financial institutions, there are complaints of coercion and force for the repayment of the interest or the loan amount,” she said.

(Views are personal. Edited by Majnu Babu).