Published May 31, 2025 | 9:03 AM ⚊ Updated Jun 11, 2025 | 9:14 AM

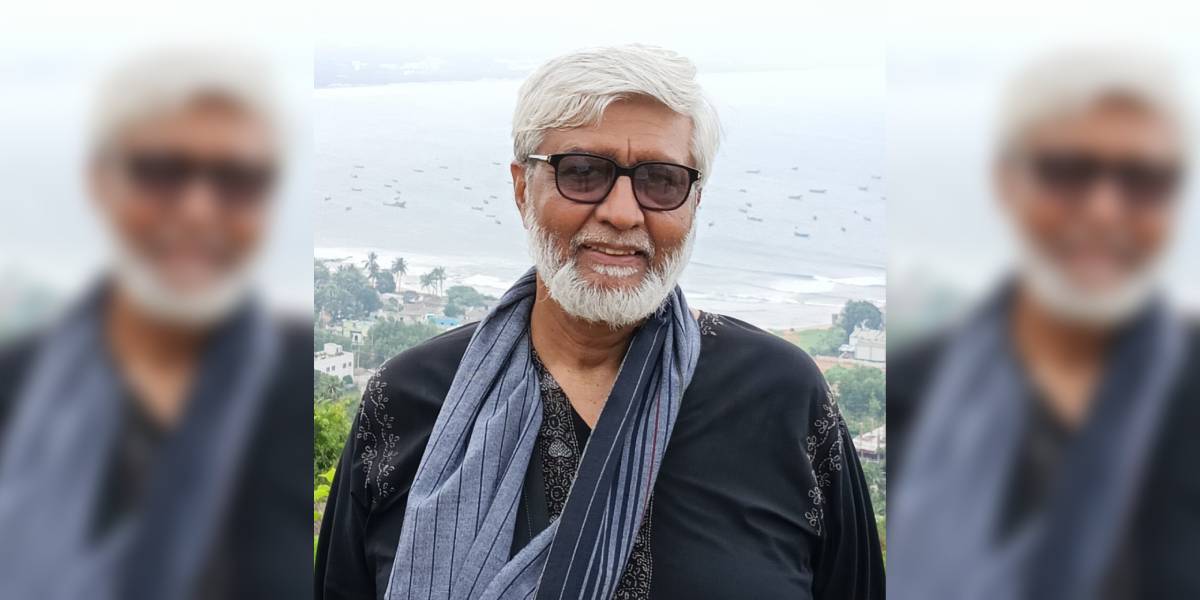

Professor Aditya Nigam. (Supplied)

Synopsis: The whole Marxist understanding that saw all kinds of market, private entrepreneurship and commodity production as ‘capitalism’ is fundamentally wrong. Trade and commerce have been with humanity from the earliest times and any attempt to forcibly erase them by placing everything under state ownership is fundamentally misplaced. Capitalism constituted a violent break from those earlier forms everywhere and there needs to be some serious rethinking about what this means in terms of formulating policies by Left governments.

Professor Aditya Nigam is a political theorist, formerly with the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, Delhi. Long associated with the Left, he has had an abiding interest in social and political movements and Marxist and post-Marxist political theory. He has also been working on developing a critique of capitalism from the perspective of the global South. His recent work has been concerned with the decolonisation of social and political theory.

Nigam writes in English, Hindi and Bengali. He is one of the founders of the political blog, Kafila.online, where he writes regularly.

He is the author of The Insurrection of Little Selves: The Crisis of Secular Nationalism in India (2006), Power and Contestation: India Since 1989, with Nivedita Menon (2007), After Utopia: Modernity, Socialism and the Postcolony (2010), Desire Named Development (2011), Decolonizing Theory: Thinking Across Traditions (2020) and Border-Marxisms and Historical Materialism: Untimely Encounters (2023).

In an exclusive interview, Professor Nigam discusses the CPI(M)’s shift towards neoliberal policies in Kerala, including privatisation in education, which signals a deeper existential crisis and erosion of its ideological moorings. The party’s pragmatism and desire to adjust to dominant powers have led to a disconnect with its leftist ideals and a potential betrayal of its historic role.

Excerpts from the interview:

Q: What prompts a leftist party like the CPI(M) in Kerala, historically opposed to neoliberal policies, to introduce a private universities bill, thereby embracing privatisation in education and aligning with the right-wing policies of the Congress and BJP?

A: It is interesting that the CPI(M) itself had been opposing the idea of allowing private universities from the time it was proposed ten years ago by the UDF government, and for many years later. So to accomplish this U-turn, it ought to have provided a credible argument – or failing that, at least accepted that its opposition to the idea in 2011 and 2016 was wrong. I don’t think it has done either. The reason for that is that all along, its stints in government, both in West Bengal and Kerala, have been guided by pragmatism and a desire to adjust to dominant powers, even when it openly contradicts the positions it has taken when not in power.

The reason is that there has never been any serious appraisal of what it means to run state governments beyond what every other party does. Nor has there been a serious study of the possibilities of addressing the so-called ‘fiscal crisis of the state’ that became the hallmark of neoliberalism’s attack on matters like government involvement in key sectors like education and health. ‘Where will the money come from?’ and ‘there is no free lunch’ became neoliberalism’s catch-phrases from day one, and it is nothing new when similar kinds of phrases are mouthed by Leftists. Neoliberalism’s drive towards privatisation of public enterprises was opposed when and where the party was in opposition, but it sang a very different tune whenever it was in power.

What was urgently needed was not a knee-jerk defence of state ownership but also its critical evaluation, addressing simultaneously the question of the ‘fiscal crisis’ and the problem of revenue generation. So, for instance, the experience of the Aam Aadmi Party government in Delhi has shown that simply by plugging leakages through corruption at various levels, the government was able to make available huge amounts of money to spend in massively revamping the infrastructure of education and health without raising taxes.

For 10 consecutive years, it could produce revenue surplus budgets, while spending almost 40 percent on education and health. This is just an example. There can be other ways of restructuring public expenditure that reduce waste and wasteful expenditure too, which can make money available for investment in sectors like education and health. So I do not take the neoliberal – and now the Left’s refrain – seriously that there is no money and therefore you have to encourage private universities.

Q: Does the Indian left’s reluctant embrace of privatisation in education, albeit with social regulation, reveal a deeper existential crisis – an inability to counter neoliberal policies effectively, and a gradual erosion of its ideological moorings? Moreover, isn’t it the truth that the Indian left is utterly clueless on how to counter neo liberalism?

A: Yes, certainly it is the expression of a deeper existential crisis within the Indian Left. You are right about the ‘erosion of its ideological moorings’, but this is not a simple matter. If by the expression ‘ideological moorings’ you mean an allegiance to the model of twentieth-century state-socialism, then that erosion was almost overnight after the collapse of state socialism and the simultaneous global ascendance of neoliberalism.

The Indian mainstream Left suddenly became like a rudderless boat, defending the state sector in words but secretly conceding that they must increasingly adjust to the demands of private capital. But the ‘erosion of its ideological moorings’ in Soviet-style socialism could also have been a good thing, had it led to a recognition that it was based on an outdated imagination of what I call ‘fossil socialism’ – a productivist imagination that simply wanted to defeat capitalism in its own game of highly destructive industrial development.

Soviet-style socialism was based on fossil fuel industrialism. Its collapse at the beginning of the 1990s and the worldwide victory of neoliberalism occurred around the same time that the Earth Conference in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 had placed the climate agenda on the table. That is where a radical critique of neoliberalism needed to be located, which meant a fundamental reordering of priorities of Left governments, moving towards more ecologically sensitive and less capital-intensive development.

However, in this respect, the CPI(M) unfortunately did not – and does not – waver from the path of ecologically destructive development, labelling ecological critiques as ‘imperialist conspiracies’. This is because it continues to believe that capitalism is the highest and most progressive achievement of human society, on which alone their ‘socialism’ can be built. It is a different matter that they may never have the chance to do so.

It is important to note that the Left in many parts of the world has shown some signs of reconfiguring their critique of neoliberalism by taking the climate and ecological crisis question seriously. The most serious critiques of privatisation (and private property) from the ecologically sensitive Left focus not on the twentieth-century binary of ‘state enterprises versus free market’ but on the commons and ‘commoning’.

Ultimately, even universities need to be rethought in that light. Simply replicating the neoliberal capitalist logic in the name of pseudo-arguments like ‘what can we do, we have no power’ and that ‘we do not exist in a socialist utopia’ only reduces an important question requiring rethinking to a pragmatic one. Poorer economies of the global South will always be short of capital and money as long as they keep chasing the highly capital-intensive dream touted by neoliberalism.

Q: Does the CPI(M)’s embrace of privatisation in education signal a betrayal of its leftist ideals and a surrender of its historic role as a champion of public education and social welfare?

A: Yes, at one level, it certainly does. However, I don’t usually like to use terms like ‘betrayal’ because when it comes to critical thinking, there should be no holy cows. If critical reappraisal of past policies and fresh thinking point towards other ways of achieving just and egalitarian goals, then we should be open to them.

So, for instance, I think the whole Marxist understanding that saw all kinds of market, private entrepreneurship and commodity production as ‘capitalism’ is fundamentally wrong. Trade and commerce have been with humanity from the earliest times, and any attempt to forcibly erase them by placing everything under state ownership is fundamentally misplaced. Capitalism constituted a violent break from those earlier forms everywhere, and there needs to be some serious rethinking about what this means in terms of formulating policies by Left governments. Unfortunately, what is happening to the CPI(M) in Kerala displays nothing of the sort.

Q: How does the Kerala CPI(M)’s shift towards neoliberal policies, as evident in its recent vision document, reconcile with its historical commitment to socialist principles and opposition to privatisation?

A: I think I have indicated in my answer to the previous two questions that simply identifying ‘state ownership’ with socialist principles is incorrect, and there needs to be a serious evaluation and critique of the entire experience of twentieth-century socialism in this respect. I underline this because in that frame, whatever was not state-owned was considered a form of privatisation – even say cooperatives and the commons (in the sense that we talk of the commons now).

My problem is with equating ‘private’ with big corporate capital. So, for instance, peasants and farmers are private owners of land. So are small and medium entrepreneurs. But when you go and make a pitch in Davos, you are talking about something else altogether. You are then talking of making Kerala a cog in the giant wheel of global corporate capital. Remember that most of us in the global South escaped the impact of the 2008 financial crisis and recession because we weren’t integrated into that machine of global corporate capital.

Q: What role do you think the decline of traditional industries, such as agriculture, and the rise of the service sector have played in shaping the Kerala CPI(M)’s economic policies and its accommodation with neoliberal capitalism?

A: That is the formal reason given by the Kerala CPI(M), but one has to see this in the context of what I said earlier. The crisis of most of the traditional industries – agriculture included – lies, of course, in the fact that they are subject to policies of the Centre, often dictated by the needs of global corporate capital that work against such industries. Most state governments, too, are sold to the same logic and therefore, do not think of breaking with that dangerous and destructive path. Pardon my saying so, but most Marxists, too, believe that ‘true salvation’ lies only in following that path.

Does the Vizhinjam port help fisherfolk or Adani? Who does the displacement of 30,000 families and the wanton destruction of the fragile ecology of the region by the SilverLine project benefit? Being built with huge loans from the Asian Development Bank and the Japan International Cooperation Agency, this semi-high-speed rail project will not only cause all-around misery for ordinary people and push the state into further debt from which it will be difficult to recover.

Moreover, these high-tech, high-cost railways are only meant for the benefit of the rich and consuming middle classes and can never be used by ordinary people. Not surprisingly, in many East Asian countries, they are reported to have shut down because they were running at a loss. So all the money of the state, even the loans that it takes from international agencies and investment from the likes of Gautam Adani, goes towards these kinds of projects. All these add up to a pursuit of the chimaera of ‘true salvation’ where the ‘rich and the beautiful’ always benefit by inflicting further miseries on the poor.

Q: How can the Kerala government balance its need for private investment and revenue generation with the potential risks of privatisation, such as increased inequality and decreased access to public goods like education and healthcare?

A: It needs to abandon the fantasy of a global corporate Kerala that it is chasing. This is a very serious question, and I do not want to make this sound frivolous. I understand that abandoning this path is not easy. Any state government wanting to do so is constrained by the Centre’s policies as well as the pressures of the global institutions. However, like all transitions, the transition out of this accursed path has to be planned and executed over the years. But the beginnings can only be made by combining this transition with the transition to a post-fossil economy, which means strengthening local networks of production and consumption, investing in them to upgrade them and providing institutional support for them.

True, no ADB or Adani will want to invest in such things unless they can take them over and corporatise them. However, once you can step out of the fantasy of this high-tech, capital-intensive path, you will not need to incur huge debts to build an economy that only services the rich. And as I indicated above, there is enough money with state governments for investing in such avenues, once they put labour, well-being of the population and the ecology at the centre of their concerns. Most of these require a very small investment.

Q: What implications does the Kerala CPI(M)’s embrace of neoliberal policies have for the state’s welfare model and social democracy, which have been crucial in reducing poverty and inequality in the past?

A: From all that I have been arguing above, it should be clear that I believe this embrace is going to destroy all the gains of the past, including significant ones like reducing inequality and poverty. It would have been far better if the Kerala CPI(M) had built on those achievements and upgraded where possible, made the shift where necessary. It is no longer a secret that 30 years of neoliberalism have hugely increased inequalities globally and have led to a ‘reverse redistribution’, where the obscenely rich have cornered more and more wealth and the poor have been more and more dispossessed. Why things should be different in Kerala’s case is hard to see.

Q: To what extent do you think the central government’s hostility towards the Kerala government, including reduced funding and GST compensation, has contributed to the state’s fiscal precariousness and its turn towards neoliberal policies?

A: These are important issues, and many of the opposition-ruled states have been facing this situation of reduced funding and holding back of GST dues. However, while reordering priorities and changing track can help in addressing fiscal precariousness, this is also something that needs to be taken up as a joint campaign by opposition state governments and parties. Apart from taking these up in legal and other forums, a campaign on restructuring centre-state relations and for a genuinely federal structure is of crucial importance today. Unfortunately, such political campaigns no longer figure in the CPI(M)’s imagination, and everything is reduced to its grossest ‘economic logic’.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).