Published Aug 27, 2025 | 9:00 AM ⚊ Updated Aug 27, 2025 | 9:00 AM

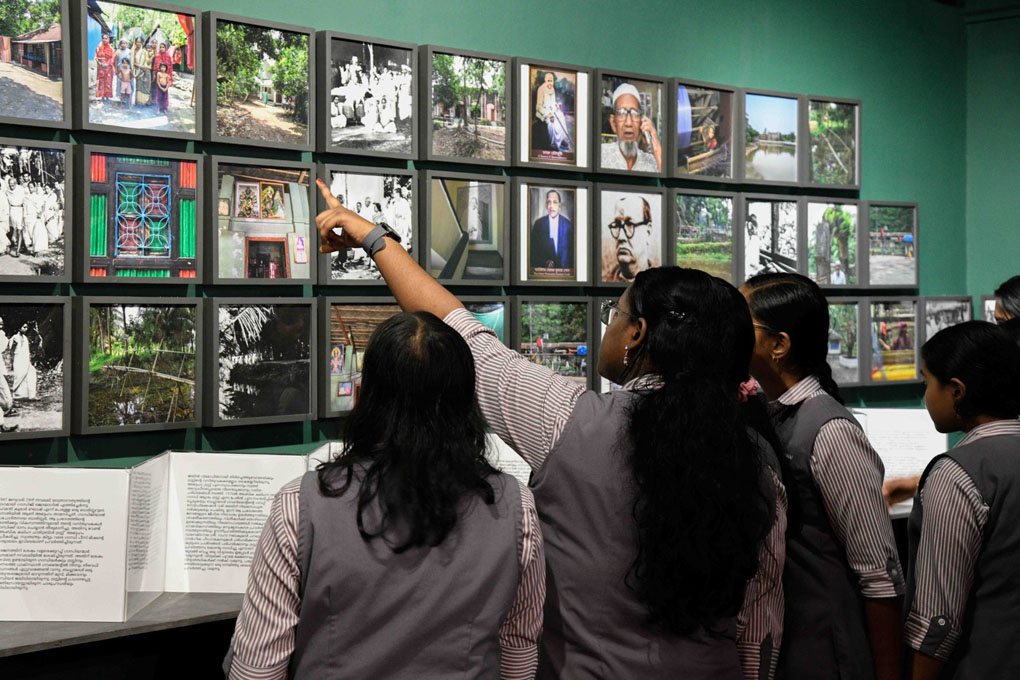

Students at the exhibition on Mahatma Gandhi held at the Lalithakala Akademi in Thrissur. (Supplied)

Synopsis: Savarkar’s projected heroism fades before the memory of Gandhi’s final journey. An exhibition traces Gandhi’s journey from Noakhali to Delhi, where he walked, fasted, and prayed to heal a fractured nation, until three bullets brought silence.

When photographer Sudheesh Yezhuvoth, artist Murali Cheeroth (Chairperson, Kerala Lalithakala Akademi), and poet PN Gopikrishnan embarked on a journey, it was not merely for a travelogue through history: it was a search for a cultural and human landscape deeply embedded with Gandhi.

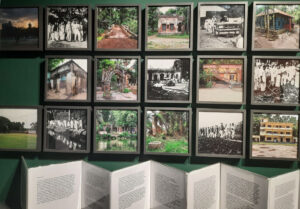

The resulting exhibition is a meditative journey through the lands Gandhi sought to heal, blending creativity with historical and political accuracy. It overcomes the barriers and challenges of cultural curation, presenting Gandhi’s journey through a creative yet historically precise lens. It goes beyond replication, using documents, images, and poetry to explore India’s cultural, moral, and human fabric that Gandhi dedicated his life to preserving.

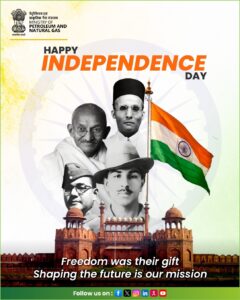

Its relevance was starkly highlighted when, during the show at the Lalithakala Akademi in Thrissur, a Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas Independence Day poster placed Vinayak Damodar Savarkar above Mahatma Gandhi, Bhagat Singh, and Subhas Chandra Bose, coincidentally in the constituency represented by Union Minister of State Suresh Gopi.

One note on display recalls that Savarkar was the eighth accused in Gandhi’s 1948 assassination trial. The contrast was striking: the media-crafted heroism of Savarkar versus the frail, fasting Gandhi, walking barefoot through Noakhali, addressing false reports from Bihar, calming Calcutta, and finally praying in Delhi until silence fell with three bullets.

But the exhibition, You I Could Not Save, Walk With Me, goes beyond that. It is not merely about the past. It is about how India remembers, and what it chooses to forget. To revisit Gandhi’s final phase is to understand his mission of love amidst hatred, his pain amidst betrayal, and his extraordinary determination to heal a nation breaking apart.

According to Sudheesh Yezhuvoth, who retraced Gandhi’s final routes with his camera, the spark was a conversation with Gopikrishnan around his book, The Story of Hindutva Politics. “He said that not many people know about Gandhi’s life during the last 18 months of his life. Then I felt I could do an exhibition about that phase of his life.”

Visitors at the exhibition. (Supplied)

Crucially, it was anchored by Gopikrishnan’s exhaustive research on Gandhi, which shaped the itinerary, the questions, and the visual syntax of the project.

What began as a plan for a tightly curated set of photographs (including archival images) soon outgrew its frame, as Sudheesh, Cheeroth, and Gopikrishnan started the journey, tracing the footsteps of Gandhiji. “The travel itself kept opening doors,” Sudheesh noted. It felt like unearthing history from ruins and joining the missing links.

The final exhibition, curated by Cheeroth and human geographer Jayaraj Sundaresan, weaves lens-based works, poems, installations, and new media into a single narrative arc. The Gandhi who emerges is not a bronze icon but a vulnerable, stubbornly ethical human being who resisted communal hatred and worked for harmony until his last breath.

For Cheeroth, the curatorial challenge was to let these fragments hold together without slipping into hagiography. “We kept asking how an icon like Gandhi can exist historically. His role was not confined to August 1947 or Partition; his influence is far more comprehensive, even in our everyday habits, including food,” he observed. “What we were looking for here was the turning point in his life, read through places, people, and practices.”

A key strand of the exhibition is collective memory assembled on the move: walking where Gandhi walked, listening where he spoke and listened, and letting those encounters shape the work.

“Sudheesh tells this exhibition in great detail, like a story,” Cheeroth said. “In an exhibition, those words also have great importance.”

The result is deliberately anti–picture-postcard: not scenic frames of Noakhali or Delhi, but a reflection of atmosphere; ruins, absences, testimonies, and the uneasy stillness. It asks viewers to come prepared, because this is history and politics around the life of a peacemaker who went deep into problems and refused to remain an outsider.

The exhibition, ‘You I Could Not Save, Walk With Me, offers a glimpse into Gandhi’s mission of love, his pain, and determination to heal and hold together a nation breaking apart.

It is historically and politically wrong to call Gandhiji’s visions ‘alternative’. By doing so, we are reducing the vision of a man who understood India in its entirety and sought to shape it systematically, according to the artists and curators. It was an act of resistance that is relevant even today. His vision was, in fact, a direct challenge to the religious fundamentalism and fanaticism that is now being advanced by various groups, including the BJP and the RSS.

What makes this visual documentation striking is its ability to capture the overwhelming darkness of the times, a darkness that still resonates with the state of affairs in a country that prides itself on being the world’s largest democracy.

“In the archival photographs displayed here, what we encounter is not merely a leader, but a man searching. Gandhi is seen walking through places scarred by riots, amidst bodies, skulls, and ruins. In those images, he appears to be walking into a kind of void, a haunting emptiness that mirrors his own visions, his desperate search for a way forward,” Cheeroth observed.

Only a handful of photographs show him in discussion with others, including leaders. More often, we see a solitary figure among the crowd, a human being searching for life amidst devastation.

In late 1946, the communal violence in Noakhali (in present-day Bangladesh) shook Gandhi deeply. Mass killings, forced conversions, rapes, and the burning of villages scarred the land.

Poet PN Gopikrishnan, Murali Cheeroth, and Sudheesh Yezhuvoth with Thushar Gandhi (second right).

At seventy-seven, instead of retreating, Gandhi chose to walk barefoot through villages along muddy tracks. He stayed in humble huts, listened to victims, and urged reconciliation. When companions warned of danger, Gandhi replied: “If I am to die, let it be in the service of Hindu-Muslim unity.”

His method was striking. He brought no armies or large Congress volunteers; only silence, prayer, and the demand that Hindus and Muslims live again as neighbours. He urged villagers to visit one another, women to move without fear, and families to reopen their doors to trust.

The journey was exhausting, yet Gandhi pressed on, knowing he could not end all hatred but hoping to plant seeds of trust. His walks also drew him into dialogue with Bengal’s Premier, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, blamed for the Calcutta killings. In Noakhali, the two undertook a “peace mission”, village to village, underscoring Gandhi’s belief that reconciliation could not be declared from above but lived out step by step in wounded communities.

While in Noakhali, Gandhi began hearing whispers of brutal violence against Muslims in Bihar. Senior Congress leaders dismissed the reports as exaggerations meant to discredit the party, and Gandhi tried to believe them. But in February 1947, Mujtaba, secretary to Minister Syed Mahmud, arrived in Noakhali with a letter detailing the atrocities, and Gandhi was shattered. “If Hindus also adopt the way of killing,” he said, “then my whole life’s mission has been in vain.” He resolved to go to Bihar once his Noakhali mission ended.

On 15 August 1947, while the rest of India celebrated independence, Mahatma Gandhi was not in Delhi. Instead, he was in Calcutta, immersed in efforts to stem communal violence sparked by Partition. The city was on the brink of civil war. Mountbatten, Nehru, and Patel all feared Calcutta would descend into chaos. Gandhi arrived with nothing but his resolve.

The Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas’ I-Day poster with Savarkar ‘towering’ over Gandhiji, Bhagat Singh, and Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose. (X)

His method was the same: presence, prayer, and persuasion. He moved into a modest house in Beliaghata, fasted and prayed. He summoned community leaders, Hindu and Muslim alike, and demanded that they pledge to stop the killings. Within days of Gandhi’s arrival, the city’s violence ebbed. Lord Mountbatten later called it the “Great Calcutta Miracle.” For Gandhi, it was proof that nonviolence still had power.

One of the show’s anchor-documents is Lord Mountbatten’s letter to Gandhi, dated 26 August 1947, which frames Gandhi’s Calcutta intervention with stark military contrast:

“My dear Gandhiji,

In the Punjab, we have 55 thousand soldiers and large-scale rioting on our hands. In Bengal, our forces consist of one man, and there is no rioting. As a serving officer, as well as an administrator, may I be allowed to pay my tribute to the One-Man Boundary Force, not forgetting his second in command, Mr. Suhrawardy…”

But peace was fragile, and Delhi soon called.

When Gandhi reached Delhi in September 1947, he found a city transformed into a ghost town. Entire Muslim neighbourhoods had been emptied; refugees from Punjab thronged every corner; the atmosphere was thick with hatred. “If Delhi goes, India goes, and with that the last hope of world peace,” he told a friend.

On 12 January 1948, Gandhi announced an indefinite fast, declaring that he would not eat until Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs pledged to end the violence. It was his final satyagraha, his last weapon.

The fast shook the conscience of the nation. Leaders of all communities came together, promising to protect each other. Gandhi had won again, but his words grew darker. He spoke more often of death, of his wish to die serving peace rather than live amidst hatred.

On 30 January 1948, as Gandhi walked to his evening prayer at Birla House, Nathuram Godse stepped forward and fired three bullets. After several failed attempts on his life, the mission of murder had finally succeeded. Gandhi fell with the words: “Hey Ram.”

That is why, when the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas Independence Day poster with Savarkar placed above Gandhi appeared during this exhibition, it was a clash of legacies. Savarkar, who preached militant nationalism and influenced the ideology of the Hindu Mahasabha, stood in stark contrast to Gandhi, who embodied nonviolence, forgiveness, and unity.

The exhibition’s historic documents and Sudheesh’s photographs recall Gandhi’s last pilgrimage of pain, from Noakhali’s muddy lanes to Delhi’s prayer ground. They reveal his vulnerability, his loneliness, and his extraordinary moral courage.

The struggle over memory is not academic. India is once again riven by identity, suspicion, and violence. In such a moment, You I Could Not Save, Walk With Me is not a nostalgic tribute but an urgent reminder. Gandhi’s final mission was not about politics or power; it was about safeguarding the very soul of India.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).