Published Feb 17, 2025 | 3:08 PM ⚊ Updated Feb 17, 2025 | 3:08 PM

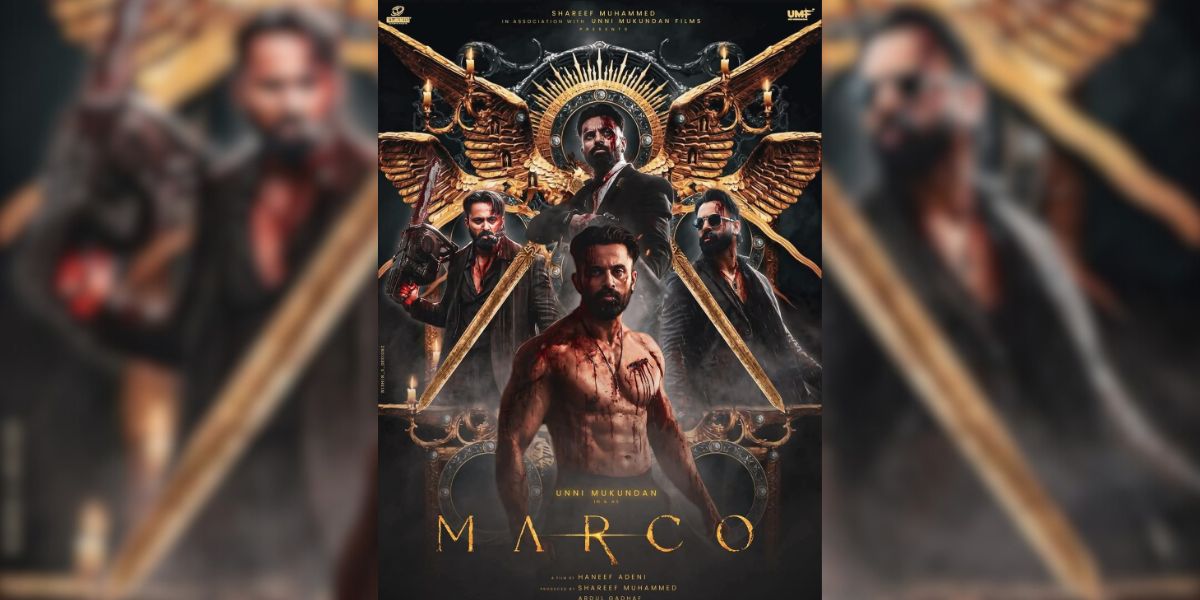

A poster of the movie Marco.

Synopsis: Marco portrays an intense level of violence. The film exposes a violent transformation in Kerala’s collective consciousness — a legitimation of violence, killing, and avenging wrongs that are guided solely by individual whims, without any moral framework to justify them. Marco serves as a lens through which viewers can perceive the visible, “subjective” violence that is often an outcome of deeper, systemic injustices.

The Malayalam film Marco (2024) — written and directed by Haneef Adeni and produced by Shareef Muhammed — portrays an intense level of violence that marks a stark departure from the norms in Malayalam cinema, particularly in its depiction of brutal, graphic violence that includes an unprecedented scale of limb-severing, organs-ripping, and the ruthless killing of children.

This unprecedented escalation in on-screen violence mirrors the increasing normalisation of violence in contemporary society, specifically in Kerala, where the line between criminal acts of brutality and societal acceptance is becoming increasingly blurred.

The extreme physical violence in Marco is noteworthy because it goes beyond the usual conventions of crime and thriller genres in Malayalam cinema. While violence has traditionally been part of action films, the level depicted in this film is exceptional, involving horrific acts such as the dismemberment of bodies, brutal murders of children, and even the killing of a pregnant woman while giving birth.

These violent acts are not just an element of the narrative but seem to serve as a means of emphasising the emotional and physical devastation that the characters endure. The grotesque nature of the violence can be interpreted as an effort to shock the audience, forcing them to confront a world where brutality is pushed to its limits.

In this context, Žižek’s concept of “symbolic violence” becomes relevant (Žižek, 2008). He argues that such explicit, physical violence is a response to the invisible and often more insidious forms of ideological or systemic violence that are rampant in society, but which are not as immediately apparent or tangible. Marco forces us to recognise the raw, palpable violence that exists beneath the surface of everyday life, revealing how such extreme acts may be a reaction to a world filled with hidden injustices.

A striking parallel that comes to mind is the Rambo series, where the protagonist, a Vietnam War veteran, avenges the state’s and society’s disregard for the immoral cause he was sent to fight for, along with his fury about it. While Rambo symbolises the rise of supremacist conservative politics in the US during the early 80s, alongside the spread of neoliberalism, Marco represents a moment in Kerala marked by the growth of violent consumerism, the legitimisation of neoliberal ideals, and the increasing acceptance of the state’s alignment with the BJP’s Hindutva conservatism.

Rambo: First Blood (1982) and Marco feature protagonists immersed in a quest for vengeance, where violence is a direct response to the harm inflicted upon them or their loved ones. Both characters exhibit a strong, muscular physique, which is emphasised in their actions throughout the films. Rambo and Marco are shown wielding heavy weaponry, with an intense physicality in their battles.

This muscle-bound imagery of the protagonist is a consistent visual cue that their violence is not only a moral reaction but also a physical manifestation of their internal struggle and desire for dominance. The stills show them both shirtless and heavily armed, showcasing their physical power and readiness to engage in battle. These moments serve to reinforce the idea that they are forces of nature, not easily deterred from their path of destruction.

In both films, the violence is not just a necessary evil but often seems reckless, bordering on unrestrained. Rambo’s killing spree in First Blood is initially sparked by a confrontation with the police, but it quickly escalates into a chaotic and relentless assault, highlighting his lack of control and the depth of his pain.

Similarly, in Marco, the protagonist’s violence is unchecked — his actions escalate from brutal acts of revenge to full-on destruction, as shown in the still where Marco is wielding a heavy machine gun. Both films present violence as a response to trauma, where the protagonists no longer operate within the constraints of society’s norms, leading to brutal, often excessive violence.

The role of the hero in Marco is portrayed by an actor who has publicly expressed his commitment to Hindutva politics. He has also openly stated that he spent his childhood in Gujarat, a state that has become a symbol of Hindutva triumphalism in the country and is infamous for the 2002 communal riots, during which women and children were allegedly massacred, mutilated and burned alive.

In Rambo: First Blood, Rambo’s enemies suffer from explosive traps and lethal precision, often resulting in serious injuries. Similarly, in Marco, the protagonist causes severe mutilations, including the dismemberment of bodies and gory, graphic kills. The physical toll on the characters is a visual representation of their psychological trauma.

In both cases, their bodies bear the marks of violence — whether through scars or the brutality they inflict on others. These mutilations symbolise the destruction of both the body and the psyche, with the violence becoming a means to express rage and reclaim agency.

Beyond this comparison, the film exposes a violent transformation in Kerala’s collective consciousness — a legitimation of violence, killing, and avenging wrongs that are guided solely by individual whims, without any moral framework to justify them. This is a trend that the state can no longer ignore or sweep under the carpet. The portrayal of this kind of violence is a dark reflection of a growing societal desensitisation to cruelty in Kerala.

In recent years, there has been an increase in incidents of extreme violence in the state, particularly involving students, such as the recent case of Veterinary college student Siddharth’s prolonged ragging and suspected murder, as well as the recent ragging incident at a nursing college where students were subjected to unprecedented torture in the name of ragging.

Domestic abuse cases are also being reported more frequently, unlike in the past when they were often concealed under the guise of family pride. Reported cases of spouses or lovers being killed by both genders, either as a means of resolving suspicions or simply to end the relationship, are also on the rise. Additionally, ritualistic killings, like the one that occurred in Thiruvalla and other areas, have become more prominent.

The frequency of these incidents, including brutal ragging cases and occult-related killings, suggests a deepening of societal norms where such violence is not just accepted but perhaps even expected.

The escalation of violence in its symbolic form is evident in cyber wars in Kerala — surprisingly, even Gandhi is defended using the most violent language against opponents — indicating a widespread acceptance of violence, even when it is superficially condemned. In Marco, violence is not simply an isolated event but a driving force that shapes the actions of the characters, particularly Marco, whose quest for vengeance is fuelled by personal loss and family devastation.

Žižek’s analysis of violence as a symptom of the breakdown of social structures offers a useful framework here. He claims that modern forms of violence are often a consequence of the failure of the symbolic order that normally holds society together, leading to a collapse of moral and ethical boundaries. This collapse is evident in Marco, where the characters find themselves increasingly trapped in cycles of retribution, each act of violence spiralling into a more grotesque one, ultimately reflecting a society in which vengeance has supplanted justice.

The marginalisation of the State in Marco speaks to the larger narrative of a society where law and order seem increasingly irrelevant in the face of unchecked criminal power. The State only makes brief, symbolic appearances — first when a customs official is complicit in the gold mafia’s operations, and again when an honest officer, pursuing the case with integrity, is brutally murdered by the mafia don. These rare appearances reflect the film’s critique of the State’s impotence in the face of criminal enterprises.

The State remains either absent or subdued throughout the film, as countless individuals are killed and mutilated in repetitive acts of violence that define each episode. The portrayal of the police as either subservient to political powers or as an instrument of the upper-class bourgeoisie echoes the deep distrust that the people of Kerala seem to have toward their institutions of law and order.

This distrust is rooted in a broader cultural attitude towards the police as mere pawns in the hands of the powerful, making the police appear both irrelevant and ineffective in ensuring justice. The film normalises this contradictory relationship by presenting the state as an abstract, almost absent force, with law enforcement depicted as either corrupt or unable to challenge the power of the criminal underworld.

This normalisation of the State’s marginalisation in Marco mirrors the consumerist, violence-driven culture of Kerala, where the law is often viewed with cynicism and resentment rather than respect, reinforcing the idea that justice in this world is not a function of the state’s moral order but of personal vengeance and brute strength.

One of the more disturbing implications of this trend in Malayalam cinema — and in society — is the normalisation of violence as a way of life on an unprecedented scale in the state’s cultural history. While similar films from Tamil Nadu have found success in the past (though never to the extent seen in Marco), this shift signals Kerala’s increasing willingness to accept brute violence as endemic, no longer external or esoteric.

Tamil films like Paruthiveeran (2007) and Naan Mahaan Alla (2010) have been regarded by critics as depicting violence at extraordinary levels. What used to be perceived as aberrant behaviour is now increasingly depicted as a necessary or even justified response to personal or societal wrongs.

In Kerala, where political violence has long been a key component of party-driven rivalries, violence against individuals, including spouses, children, and marginalised communities, is becoming alarmingly common. The emotional and physical torment that individuals undergo in real life is now reflected in films like Marco, which acts as a mirror to these increasingly accepted forms of violence.

Žižek’s view that violence is often an expression of the subject’s desperate attempt to regain agency in an alienated and oppressive system is central to this analysis.

In Marco, the protagonist’s violent acts, though motivated by grief and vengeance, also serve as a desperate assertion of control in a world where social and familial structures have been torn apart. The film reflects the idea that, in a world increasingly bereft of meaning or justice, violence becomes a desperate but seemingly inevitable attempt to restore order.

The depiction of extreme violence in Marco also blurs the line between fiction and reality. The graphic nature of the violence presented in the film might be seen as sensationalist, but it also mirrors the escalating instances of brutality that have been reported in the media. This rise in violence, not only in party politics but also in personal relationships, creates a chilling overlap between the violence depicted on screen and the violence seen in real life.

As viewers, we are forced to question whether such acts of terror are truly the product of imagination, or if they are part of an emerging social trend where physical brutality is becoming an acceptable means of conflict resolution. Here, Žižek’s concept of “objective violence” (violence that arises from systemic oppression and is often invisible) becomes particularly relevant.

Marco serves as a lens through which viewers can perceive the visible, “subjective” violence that is often an outcome of deeper, systemic injustices. The graphic violence in the film acts as an extreme manifestation of the underlying social decay and moral disintegration that may be less obvious but no less pervasive in real-life social structures.

On a psychological level, the film taps into the anxieties surrounding powerlessness, revenge, and the collapse of moral and ethical boundaries in a society that is increasingly vulnerable to violent impulses. The protagonist’s transformation from a man seeking justice into a vengeful avenger mirrors how violence often becomes an escalating cycle. As society continues to be exposed to such extreme portrayals of violence, one must ask how this affects collective behaviour and the moral compass of the population.

Does it contribute to a culture of fear, or does it serve as catharsis, allowing audiences to release their own bottled-up frustrations through the experience of cinematic violence? Žižek argues that, in a world where symbolic and structural violence prevail, individuals may feel compelled to act out in ways that reassert their agency, even if it means resorting to extreme and destructive means. Marco is a narrative that emphasises this deep psychological tension, where vengeance and violence become the only perceived avenues of restoring order and meaning.

There’s also the broader question of how violence is being incorporated into the cultural fabric of Kerala. For years, the state has struggled with violence linked to political rivalries, and while this kind of violence was often presented in a politically charged context, the scenes of brutal violence in Marco suggest a shift towards a more individualistic justification for such acts.

The increasing representation of ordinary people resorting to extraordinary violence in films could be seen as a commentary on the breakdown of community values and the rise of self-interest as the dominant force driving individuals to extreme acts. Žižek’s analysis of the “logic of violence” suggests that, in a society where the traditional moral frameworks are eroding, individuals may come to see violence as an acceptable or even inevitable way of achieving their goals.

In Marco, this individualistic violence is not just an expression of personal rage but also a symptom of a broader cultural shift where violence is increasingly becoming a normalised mode of engagement with the world.

Marco, by pushing the limits of violence in Malayalam cinema, forces viewers to confront the normalisation of brutality in both the fictional world and in their own.

This shift in Malayalam cinema, alongside the increasing instances of real-world violence, speaks to a deeper transformation in societal norms, where the boundaries between what is considered acceptable and what is deemed horrific are becoming increasingly blurred. The violence in Marco is, thus, not simply an expression of individual rage but a larger societal symptom, manifesting in the breakdown of social norms, the collapse of moral order, and the increasingly widespread acceptance of violence as a legitimate tool for personal and social reconciliation.

(Reference: Žižek, S. (2008). Violence: Six Sideways Reflections. Picador. Views expressed here are personal.)