Published Apr 14, 2025 | 12:30 PM ⚊ Updated Apr 14, 2025 | 6:45 PM

Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar in his office (Wikimedia Commons)

This article was originally published on 24 December 2024 and has been republished on 14 April 2025, the occasion of Ambedkar Jayanti.

The legacy of Dr BR Ambedkar, the architect of the Indian Constitution and a champion for the rights of the marginalised, remains fiercely contested in contemporary Indian politics.

The recent controversial remarks by Union Home Minister Amit Shah, mocking Ambedkar’s repeated invocation, in Parliament, the subsequent backlash, and the broader efforts by the BJP-led NDA alliance to associate themselves with the anti-caste champion have reignited debates over Ambedkar’s stance towards organisations like the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), its precursor, the Hindu Mahasabha, and Hindu right icons such as VD Savarkar.

Ambedkar’s legacy is one of radical social reform and an uncompromising commitment to equality. Through his vast body of writings, public speeches, and private correspondence, he was unequivocally critical of the RSS, Savarkar’s ideology, and the hierarchical and exclusionary ideologies that underpinned them.

While political parties may invoke his name to bolster their credibility, Ambedkar’s vision remains a challenge to those who seek to co-opt it without confronting the systemic inequalities he spent his life fighting against.

Efforts to associate Ambedkar with the RSS and Savarkar, often through selective readings of history, must be viewed through this historical lens.

Ambedkar’s own vast body of writing, private correspondence, and public speeches reveal a consistent commitment to dismantling caste and fostering an inclusive, democratic India – principles that often placed him at odds with both the Congress party and the Hindu right.

Claims that Ambedkar was “impressed” by the RSS are difficult to reconcile with historical evidence. In fact, on 14 May 1951, Ambedkar made scathing remarks about the RSS in Parliament, referring to it as a “dangerous association” alongside the Akali Dal. He said: “May I mention the RSS. and Akali Dal? Some of them are very dangerous associations.” [See Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches, Vol. 15, ed. Vasant Moon, Govt. of Maharashtra, 1997, p. 560; Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 11, Part Two, 14 May 1951, pp. 8687–90.]

His warning was unequivocal and part of a broader critique of organisations he deemed detrimental to the democratic and pluralistic fabric of India.

This position is further corroborated in the 1951 manifesto of the Scheduled Castes Federation, an organisation founded by Ambedkar in 1942 to campaign for the rights of the Dalit community. The manifesto explicitly stated that the Federation would not ally with “reactionary” entities such as the RSS or the Hindu Mahasabha.

“The Scheduled Castes Federation will not have any alliance with any reactionary party such as the Hindu Mahasabha or the RSS… the Communist Party, the objectives of which are to destroy individual freedom and Parliamentary Democracy and substitute a dictatorship in its place [and] will not join a political party which is already totalitarian and which does not permit an opposition party to grow.”

Among the many efforts to appropriate Ambedkar’s legacy by right-wing politics in India is the claim of “mutual admiration” between Ambedkar and Savarkar, based on their early correspondence. This is often presented in contrast to Ambedkar’s pronounced conflict with MK Gandhi and later the Nehru Congress.

In a letter dated 18 February 1933, Ambedkar does indeed express appreciation for Savarkar’s work in the realm of social reform, particularly his efforts to open temples to Dalits. However, this appreciation was tempered by sharp ideological disagreements. [See Letters of Ambedkar by Dr Surendra Ajnat, 1993; Page 87.]

Ambedkar criticised Savarkar’s endorsement of Chaturvarnya (the ancient caste system, which divided society into four classes or varnas) in the same letter: “That you still use the jargon of Chaturvarnya, although you qualify it by basing it on merit, is rather unfortunate. However, I hope that, in the course of time, you will discard this mischievous jargon,” he wrote.

Furthermore, in his seminal work Pakistan or the Partition of India (1946), Ambedkar extensively critiqued Savarkar’s vision for India, terming it dangerous and “illogical, if not queer.”

“Mr. Savarkar does not admit that the Hindu Mahasabha was started to counteract the Muslim League, nor that as soon as the problems arising out of the communal award are resolved to the satisfaction of both Hindus and Musalmans, the Hindu Mahasabha will cease to exist. Mr. Savarkar insists that the Hindu Mahasabha must continue to function even after India attains political independence.”

Ambedkar further equated Savarkar’s vision with that of Mohammad Ali Jinnah, criticising his insistence on a unified India under Hindu dominance as illogical and harmful, likening it to failed models of coexistence in Austria and Turkey.

“Strange as it may seem, Mr. Savarkar and Mr. Jinnah, rather than being opposed to each other on the one-nation versus two-nations issue, are in complete agreement. Both not only agree but insist that there are two nations in India: one being the Muslim nation and the other the Hindu nation.

“Mr. Savarkar… insists that although there are two nations in India, the country should not be divided. Instead, the two nations should coexist in one country under a single constitution. This constitution, he proposes, should ensure that the Hindu nation occupies the predominant position it deserves, while the Muslim nation lives in a state of subordinate cooperation with the Hindu nation.”

Ambedkar’s vision for India, articulated most powerfully in Annihilation of Caste – an undelivered speech written for an anti-caste convention held in Lahore in 1936 – starkly contrasts with the ideologies espoused by the RSS and Savarkar. Ambedkar lambasted the caste system for stifling reform, perpetuating inequality, and corroding the ethical foundations of Hindu society. His proposed ideal was a society built on liberty, equality, and fraternity – principles he saw as foundational to democracy and antithetical to caste and communal hierarchies.

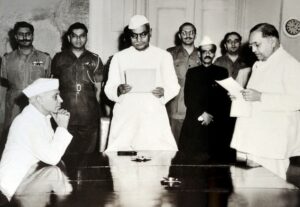

Ambedkar is sworn in as India’s first Law and Justice Minister (Wikimedia commons)

While Amit Shah’s remarks in Parliament emphasised Ambedkar’s dissatisfaction with the Congress, they overlooked his critiques of Hindu nationalism and his rejection of organisations like the RSS.

Ambedkar’s disillusionment with the Congress stemmed not from alignment with the Hindu right but from his broader critique of the Indian political elite’s failure to address caste and social inequities.

The Hindu Code Bill controversy provides another lens through which to understand Ambedkar’s fraught relationship with conservative factions in Indian society.

The Bill, spearheaded by Ambedkar with backing from Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, sought to overhaul Hindu personal laws to ensure greater rights for women. However, it faced staunch resistance from conservative factions within and outside the legislature, including Rajendra Prasad and JB Kripalani within the Congress Party, and external critics such as the Hindu Mahasabha.

In her 2012 book, Debating Patriarchy: The Hindu Code Bill Controversy in India (1941–1956), Chitra Sinha writes:

“The stir caused by the Bill in the political sphere was unprecedented, though there has been almost no detailed historical account of the event. On one side of the spectrum were liberals like Gandhi, Nehru and Ambedkar; on the other side ranged a very powerful segment of the legislature, including Rajendra Prasad and Acharya JB Kripalani within the Congress Party, and Shyama Prasad Mukherjee and other leaders of the Hindu Mahasabha.

“It became clear to [Nehru] that the Bill was extracting a political cost. The Hindu Mahasabha exploited the situation and mobilised public opinion against the Bill. On 12 December 1949, a demonstration of over 500 people gathered outside Parliament House, chanting ‘Down with the Hindu Code Bill’ and ‘Down with the Nehru Government’. For Nehru, it was a revealing experience.”

With the first general elections looming in 1952, Nehru decided to put the Bill on the back burner. Ambedkar’s resignation in 1951 from the first Nehru cabinet underscored his frustration with the political climate, though the Bill was essentially passed in fragments a few years later anyway.

“As the debate on the Hindu Code Bill progressed, anti-Ambedkar sentiment increasingly obstructed its progress. Such was the intensity of the opposition to Ambedkar that Nehru even considered reshuffling the Cabinet and appointing a more congenial Law Minister. Indeed, during 1955 and 1956, when the Hindu Code Bill was enacted in fragments, Ambedkar’s absence has been cited as a reason for the smoother passage of the Bill,” Sinha writes.

“Ambedkar has gone on record as stating that he considered his work on the Hindu Code Bill to be as significant as his role in formulating the Indian Constitution. Ambedkar argued that Hindu society was static, with laws left to divine authority and both shudras and women exploited by rigid structures.”

(Edited by Majnu Babu)