Published Dec 23, 2024 | 9:00 AM ⚊ Updated Dec 23, 2024 | 9:00 AM

Ambedkar statue in Hyderabad. (South First)

Why is Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar suddenly so important for India’s national political parties, the BJP and the Congress? The answer in a broader sense is that the community for which he is the ideological icon, variously called Scheduled Castes or Dalits, constitute about 17 percent of India’s population and spread somewhat evenly over most Indian states.

But Uttar Pradesh, where the shoe pinches for the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, is where the real action is.

With the demise of Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) founder Kanshi Ram and the decline of his political heir Mayawati, the country’s most populous state is up for grabs in a political sense, and the Dalit vote may well prove to be decisive in the fractured voter demographic of the state in the coming years.

According to the 2011 census, Dalits made up 21 percent of UP’s population, well above the national average. The BJP won only 33 of the 80 Lok Sabha seats from Uttar Pradesh this year — something that is being overlooked in the loud cheers over its recent electoral victories in Haryana and Maharashtra, for which it had to struggle anyway.

The Indian National Congress won six UP seats in a comeback mood and the Samajwadi Party, which is now part of the Congress-led INDIA grouping, won as many as 37.

All those numbers not mentioned by loud prime-time anchors really explain the scuffles, theatrics, noise and acrimony that we witnessed in and outside the national parliament last week.

Picture the Dalits of Uttar Pradesh like an asset-rich company up for takeover by rival bidders. With Dalit votes crucial elsewhere in the country as well, the BJP and the Congress are both keen to appropriate the Ambedkar legacy — a sport that is not new.

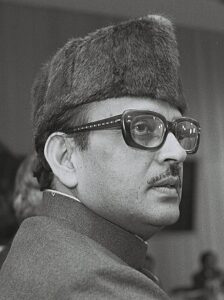

Former Prime Minister VP Singh. (Wikimedia Commons)

In 1990, Prime Minister VP Singh’s Janata Dal-led National Front coalition government unveiled Ambedkar’s portrait in the Central Hall of the old Parliament House and also awarded him the nation’s highest civilian honour, the Bharat Ratna, a full 34 years after the death of the US-educated economist-turned-politician who founded the Republican Party of India shortly before his demise.

While the BJP cites a technical reason, that the BJP supported (from outside) the VP Singh government before pulling the rug from under his feet, as a claim over the honour for Ambedkar, BSP leader Mayawati said a decade ago that the BJP was not happy with the Bharat Ratna award to him. That is understandable.

Loud pro-Ambedkar noises from the BJP today must be compared with its relative silence or reticence in 1990 when it was busy projecting itself as the future builder of a Ram temple at the disputed Babri Masjid site in Ayodhya.

Neither my memories of those days as an active reporter nor a web search throw up any effusive statement from the BJP in support of the Ambedkar legacy in 1990. The Hindutva champions’ earlier relations with Ambedkar were also uneasy at best.

Ambedkar resigned from the cabinet of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in 1951 because the government could not pass the Hindu Code Bill that was opposed by Hindu Mahasabha, the BJP’s forerunner in national politics as a Hindutva party in line with the political philosophy of Veer Damodar Savarkar.

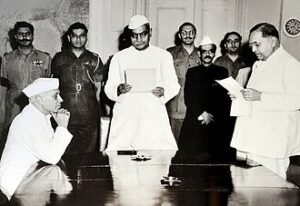

Babasaheb Ambedkar (R) being sworn in as India’s first Law Minister by President Dr Rajendra Prasad on 8 May 1950. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru looks on. (Wikimedia Commons)

Both Savarkar and Hindu Mahasabha leader Syama Prasad Mukherjee are BJP’s ideological icons. The Hindu Code Bill sought to empower women but Hindu Mahasabha publicly opposed on the grounds that it went against tradition and culture.

Savarkar was in favour of Dalits joining his mainstream Hindu Rashtra project, whereas Ambedkar wanted a radical transformation of the Hindu society that was not in line with the Hindutva idea of unity that did not build in significant elements of affirmative action and equality. Savarkar wanted Hindu unity but did not speak up for ending the caste system — which was Ambedkar’s aim.

You only have to look at the way Ambedkar dressed to understand his views. Nobel prize-winning writer VS Naipaul cites Ambedkar’s love for wearing Western ties and suits as symbolic of his appreciation of Occidental influence that helped him empower the Dalits.

Ambedkar was preoccupied with the idea of building a casteless society. Fighting British rule was not his top priority.

“There is no use having Swaraj if you cannot defend it… only when the Hindu society becomes a casteless society can it hope to have strength enough to defend itself,” he wrote in 1936.

After Ambedkar’s demise, the Congress under Nehru and his daughter Indira Gandhi successfully won Dalit votes in most part of India by a combination of affirmative action measures such as job reservation, advocacy of equal rights, and support for Dalits against violence by upper castes in rural areas.

Mayawati. (Wikimedia Commons)

The Congress also propped up leaders like Babu Jagjivan Ram, who went on to become India’s defence minister, something that helped fortify the party’s Dalit support base.

However, ground conditions and everyday lives of Dalits facing social discrimination did not change much. Landless and powerless in most cases, they still form the lowest rung of Indian society — and it must be mentioned that they did not even qualify as “shudras” — considered the lowest rung of the traditional Hindu social organisation.

The Congress lost its hold over Dalits over the years in Uttar Pradesh as the average Dalit hardly gained from economic growth or job reservations, The BSP, espousing a radical Ambedkarite view against the Congress party’s moderate reformist approach, surged under Kanshi Ram, who anointed Mayawati as UP’s first Dalit chief minister and the nation’s first Dalit woman to run a state.

But her indifferent governance and inability to take other communities along has led to the decline of the BSP. Uttar Pradesh is thus a fertile ground for Dalit-vote-hunting again. The demise of neighbouring Bihar’s towering Dalit leader Ram Vilas Paswan who like Mayawati aligned himself with the BJP has left a substantial Dalit vote vacuum in Bihar as well.

The BJP and the Congress are both trying afresh to impress Dalits in the Hindi heartland states through scuffles and tussles in a more-Ambedkarite-than-thou game.

Chandrashekhar Azad Ravan. (Wikimedia Commons)

The Congress has decidedly honoured Ambedkar’s values. The Dalit icon had disagreements with Nehru and the Congress over the pace of social change but in terms of direction, the Congress party’s Western-inspired progressive egalitarianism that contrasts the BJP’s cultural conservatism aligns better with Ambedkarites.

The Dalit vote in UP has become more crucial than ever for the BJP, which now has an unquestioned hold over only one state: Modi’s home state Gujarat. State assembly elections in UP are due in mid-2027, and the BJP’s favourite recipe of Hindu consolidation is in serious doubt after recent Lok Sabha results.

A lot now depends on how new-age, younger Dalits feel about the two parties — or other parties such as the Azad Samaj Party founded by Chandrashekhar Azad, who is a sitting MP from UP.

The leader has added “Ravan” to his name in a clear taunt at BJP’s politics that idealises and idolises Lord Rama of Hinduism’s rich pantheon. His party takes inspiration from Kanshi Ram but stands as a counter to Mayawati.

Watch out for this man. He is only 38 years old and seems to have a mind similar to Dr. Ambedkar himself. He keeps his voice loud, options open and plans secret.

(The writer is a senior journalist and commentator who has worked for Reuters, The Economic Times, Business Standard, and Hindustan Times. He tweets on X as @madversity. Views are personal. Edited by Majnu Babu).