Published Feb 19, 2025 | 3:00 PM ⚊ Updated Mar 05, 2025 | 4:19 PM

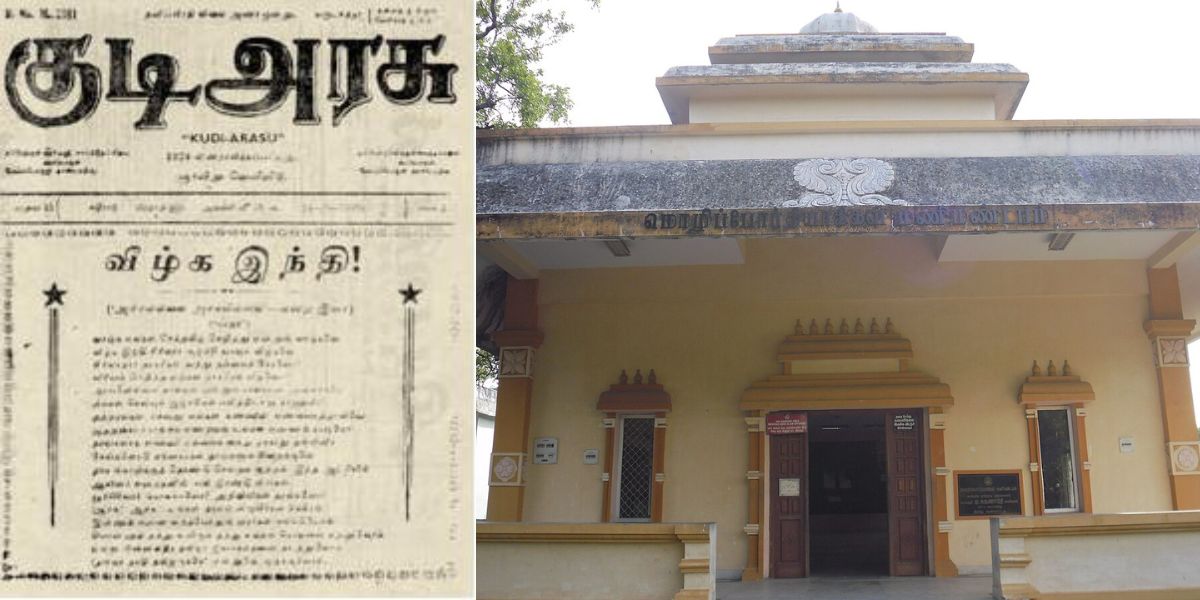

Front page of Periyar EV Ramasamy's periodical Kudiyarasu (3 September 1939). The headline reads "Veezhga Indhi" (Down with Hindi), and a memorial for those who died in the Anti-Hindi imposition agitations in Chennai.

Synopsis: Tamil Nadu has a long history of resisting Hindi imposition, rooted in the Dravidian movement’s ideological opposition to linguistic dominance. From the early protests in the 1930s to the mass agitations of the 1960s and beyond, the state has continually rejected attempts to make Hindi mandatory in education and administration. The anti-Hindi struggle was not just about language but also about preserving Tamil identity and resisting cultural homogenisation. This article explores the key moments, political influences, and evolving nature of the movement, drawing parallels to contemporary opposition against policies like the National Education Policy and the Three-Language Policy.

“Since land, country, language, art, and wealth are all referred to with feminine names in Tamil tradition (such as Motherland, Mother Tongue, etc.), it is the duty of women, even more than men, to safeguard the language. Therefore, a Tamil Women’s Conference is essential. Every Tamil-supporting man should send the women in his household to participate in this event,” quoted Nivedita Louis in her book “1938 Mudhal Mozhi Poril Pengal.”

This was the second declaration of the first Women’s Conference held in Chennai by Dravidian activists in 1938.

The 1920s saw Mahatma Gandhi’s initiative to teach Hindi as part of the larger freedom movement. During this period, women played a significant role by travelling across cities and villages to teach Hindi. In the Madras Presidency, figures such as Durgabai Deshmukh and Ambujam Ammal were among those actively involved in promoting the language, according to writer and publisher Nivedita Louis.

However, widespread resistance emerged only after Rajaji’s government order made Hindi compulsory in schools in 1938. This move sparked opposition, particularly under the leadership of female revolutionaries like Dr Dharmambal Ammaiyar, who intensified resistance to Hindi imposition.

Periyar EV Ramasamy played a crucial role in guiding these women, encouraging them to lead protests at schools.

In 1938, protests erupted across Tamil Nadu in response to the forced imposition of Hindi. While sporadic protests had occurred before, it was this year that the Tamil language rights movement gained significant momentum, largely due to the active involvement of women. Periyar’s leadership was central in mobilising women, as highlighted by Louis in her book.

In April 1938, the government’s order making Hindi compulsory in schools ignited the Tamil language movement into full-fledged protests. Dr Dharmambal Ammaiyar founded the Thyagaraya Nagar Women’s Progressive Association and organised the first-ever women’s conference on the issue. It was at this conference that Meenambal Sivaraj conferred the title “Periyar” upon EV Ramasamy.

Held on 13 November 1938, the conference was led by prominent women activists such as Neelambikai Ammaiyar, daughter of Tamil scholar Maraimalai Adigal, and figures like Thamaraikanni Ammaiyar, Moovalur Ramamirtham Ammaiyar, Pandithai A Narayani, Meenambal Sivaraj, and Kalaimagal Ammaiyar.

Periyar, who had founded the Self-Respect Movement in 1925, encouraged women to take an active role not only in anti-Hindi protests but also in broader political struggles. The Women’s Progressive Association organised mass gatherings, conferences, and jail-filling protests, bolstering the anti-Hindi movement.

The 1938 women’s conference was pivotal in uniting various organisations, including the Thanithamizh Iyakkam, Islamic associations, and Dravidian groups, in the fight against Hindi imposition.

While the conference was centred on women’s rights, its resolutions primarily focused on language rights. According to Louis, key resolutions passed at the conference included:

Hundreds of women leaders actively participated in the Women’s Progressive Association. From Dr Dharmambal’s speech to Thamaraikanni Ammaiyar’s fiery addresses, the entire conference revolved around Tamil identity and linguistic rights.

Thamaraikanni Ammaiyar declared that the purpose of the women’s conference was to awaken Tamilians, emphasising that the imposition of Hindi would lead to an influx of North Indians into Tamil Nadu, a concern she raised 85 years ago.

She clarified, “If Hindi remains in its rightful place, we have no issue with it. But when it forcefully takes the place of our mother tongue, we resist it. In Tamil Nadu, I have no objection to those who voluntarily learn Hindi. That is my stance,” quoted Louis in her book.

The 1938 women’s conference not only called for protests but also emphasised organising fill-the-jails actions, with women actively participating alongside men. Periyar reinforced this message in his speech, encouraging women to partake in the satyagraha against Hindi imposition.

The 1938 women’s conference not only called for protests but also emphasised organising fill-the-jails actions, with women actively participating alongside men. Periyar reinforced this message in his speech, encouraging women to partake in the satyagraha against Hindi imposition.

Inspired by this call, just two days after the conference, a group of women attempted to stage a satyagraha against Hindi imposition in front of the Hindu Theological School in Chennai.

Police arrested key figures like Dr Dharmambal, Moovalur Ramamirtham Ammaiyar, Malarmugathammaiyar, Seethammal (Dharmambal’s daughter-in-law), and several others, including children.

Even in court, these women used the platform to protest, refusing to plead guilty and choosing imprisonment instead. In the first phase of the anti-Hindi struggle, 73 women and 32 children were jailed, alongside 1,164 men. Many activists suffered police brutality, with some dying due to injuries and illness. Among the martyrs were Padmavati.

Padmavati’s tragic death in 1938 exemplified the high cost of resistance. She was arrested for wearing a saree with the slogan “Tamil Vazhga” (Long Live Tamil) and demanding an independent Tamil Nadu.

She died as a result of the severe torture by the police. Her tombstone at Moolakothalam Cemetery in Chennai commemorates this painful event. The memorial was inaugurated on 21 September 1974 by EVR Maniyammai, K. Rajaram, who was then the labour welfare minister, and NV Natarasan, who was then the minister for Backward Classes.

The movement ultimately led to the martyrdom of Natarasan and Thalamuthu in 1939, who died while imprisoned for their involvement in the Tamil cause.

These sacrifices stand as a testament to the deep-rooted resistance of Tamil women against Hindi imposition, marking their unparalleled contribution to the language struggle. The government’s eventual reversal of the policy to make Hindi compulsory in schools was a direct result of these efforts.

In 1948, during Omandur Ramasamy’s tenure as chief minister of Madras, the state witnessed a surge in protests against the imposition of Hindi. This movement, known as the Second Language War, was ignited by the government’s decision to reintroduce compulsory Hindi in the Madras Presidency.

In 1948, during Omandur Ramasamy’s tenure as chief minister of Madras, the state witnessed a surge in protests against the imposition of Hindi. This movement, known as the Second Language War, was ignited by the government’s decision to reintroduce compulsory Hindi in the Madras Presidency.

Initially, Hindi was to be mandatory only in the regions of present-day Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, and Karnataka, while Tamil Nadu was to have it as an optional subject.

However, the decision was later extended to Tamil Nadu, which led to intense opposition across the state. Amidst widespread protests, the government was forced to withdraw the order in 1950.

One of the most poignant moments of this struggle was the sacrifice of Dhanalakshmi, who faced brutal harassment by the police during the protests. She was forcibly loaded into a police truck, driven 40 miles from her home, and abandoned in an unfamiliar place.

The ordeal led to a miscarriage, severe health complications, and eventually her death. Her tombstone at Moolakothalam Cemetery in Chennai records that she died due to the hardships endured during the protest, underscoring the personal cost of standing up for linguistic rights.

The situation escalated in 1965 when the Union government declared Hindi as the official language of India, triggering a massive wave of protests in Tamil Nadu. To assuage concerns from non-Hindi-speaking states, the Official Languages Act of 1963 allowed English to continue alongside Hindi.

However, there was a growing demand to change the phrase “may continue” to “shall continue” to ensure the permanence of English. CN Annadurai, popularly known as Anna, the leader of the DMK, famously said in Rajya Sabha, “If they mean the same, why hesitate to change it?.”

Despite the opposition, the law was passed on 23 April 1963.

The protests against Hindi imposition reached a new high as students and the public took to the streets. The 1965 movement was not just a linguistic struggle but a fight for Tamil identity and autonomy, leading to significant political changes in the state.

Theeyil Vendha Tamil Puligal, Hindi Edhirpu Thyagigal Varalaru (The Tamil Tigers who were Burned in Fire: The History of Anti-Hindi Martyrs) by Vidudhalai noted several instances where people lost their lives during the protests, including self-immolation.

Keelapalur Chinnasami became the first person in the world to self-immolate for language rights on 25 January 1964. In his final words, he declared, “I am dying so that Tamil may live. What I did today will surely win.”

On 25 January 1965, student rallies erupted across Tamil Nadu, culminating in a violent attack on protesters in Madurai. One of the protestors, Kodambakkam Sivalingam, vowed, “Tomorrow, when Hindi becomes the official language, it will be a day of mourning for us.”

On 26 January 1965, he set himself on fire, chanting, “My life for Tamil, my body for the fire.”

The following night, Virugambakkam Aranganathan also self-immolated in a desperate protest against the Hindi imposition. He declared that he would rather burn himself than see Tamil suffer under the weight of a national language policy that threatened his mother tongue.

As the protests escalated, Kiranur Muthu, consumed poison on 27 January 1965, ending his life in protest. On the same day, Sivagangai Rajendran, a student from Annamalai University, was killed when the police opened fire on a peaceful protest march towards Chidambaram. Over 3,000 students had gathered, and while stones were thrown to disperse the crowd, it was the bullets that silenced their voices.

On 11 February 1965, Sathyamangalam Muthu, who had raised the slogan “Long live Tamil, down with Hindi,” set himself on fire, succumbing to his injuries a week later. His final words were, “Tamil students must not be harmed; Tamil must live, the Tamil race must survive.”

Other notable sacrifices include Ayyampalayam Veerappan, a school headmaster who led student protests. Devastated by the government’s repression, he submitted his resignation on 10 February 1965, before setting himself on fire the next day. Viralimali Shanmugam followed suit on 25 February 1965, consuming poison and declaring, “Tamil people, wake up by seeing my body! The Tamil mother’s feet are stained with blood.”

Coimbatore’s Peelamedu Thandapani, unwilling to accept a life where Tamil was suppressed, took his own life on 2 March 1965, with the words, “My life for Tamil, my body for the soil.” Similarly, Mayiladuthurai Sarangapani set himself on fire, shouting, “Long live Tamil,” in an anguished protest against the continued erosion of Tamil’s place in the nation.

The intense anti-Hindi agitation and the sacrifices made by the people led to a political shift in Tamil Nadu. Following the DMK’s victory in the 1967 elections, the newly formed government, under chief minister CN Annadurai officially implemented the Two-Language Policy in 1968.

This policy, which replaced the earlier three-language formula, proposed by the Kothari Commission in 1966, reinforced Tamil and English as the state’s official languages in education and administration.

In 1986, the introduction of Jawahar Navodaya Vidyalayas in Tamil Nadu was perceived as another attempt to impose Hindi.

Former chief minister Karunanidhi led a massive protest against this perceived threat to Tamil. The current discourse surrounding the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 and the PM-Shri schools bears strong similarities to the 1986 movement.

Tamil Nadu continues to oppose the NEP’s three-language policy. This modern struggle mirrors the historical resistance to Hindi imposition, highlighting the ongoing tension between linguistic identity and national policy.

The sacrifices of countless individuals during these movements laid the foundation for Tamil Nadu’s enduring commitment to preserving its linguistic and cultural heritage.

As the debate around Hindi imposition resurfaces in contemporary politics, the echoes of past struggles continue to resonate, reminding the state of the price paid for linguistic autonomy.

The Dravidian movement’s opposition to the imposition of Hindi is rooted in a deep ideological framework that challenges not just the language but the power structures it represents.

Prominent researcher S Anandhi explained that the resistance to Hindi is rooted in a broader ideological context — one that views the imposition of Hindi as an extension of Sanskrit, a language historically associated with Brahmanical scriptures that perpetuated caste and gender hierarchies.

“Due to its linguistic proximity to Sanskrit, Hindi was perceived as a tool for maintaining social oppression, particularly against marginalised communities. Anandhi emphasises that this resistance is not just about the language but its association with the power dynamics of the ruling elite,” Anandhi said.

Thirumurugan Gandhi, leader of the May 17 Movement that works for Tamil civil rights, echoed this sentiment and argued that the imposition of Hindi is part of a broader strategy to consolidate various forms of dominance.

He contended that the Dravidian movement opposed Hindi because they saw it as an extension of Sanskrit, through which Aryan and Hindutva hegemony was being enforced upon Tamil Nadu.

Gandhi highlighted that by enforcing their language upon Tamil speakers, there was an intention to transform them into second-class citizens, ensuring the continuation of socio-political dominance. According to him, this is the strategy employed to exert control over Tamil society.

Anandhi further elaborated on the second major argument of the Dravidian movement against Hindi.

She said that one of the key reasons for the opposition was Hindi’s perceived inadequacy as a language for modern, progressive thought. Prominent figures in the movement, such as former deputy minister P Subbarayan, argued that Hindi lacked the intellectual and scientific depth necessary for societal advancement.

Subbarayan’s stance, articulated in 1955, rejected the idea of Hindi replacing English, which was regarded as essential for scientific, technological, and rational discourse.

He argued that Hindi was neither as developed nor as useful as Tamil or Bengali and advocated for the continued use of English as the official language until Hindi could reach a standard sufficient to replace it.

The ideological struggle against Hindi came to a head during the 1965 anti-Hindi agitations led by the DMK. As Anandhi pointed out, these protests ultimately led to the 1967 Official Languages Amendment Act, which ensured that English would continue to play a central role in governance, alongside Tamil.

This victory marked a critical moment for the Dravidian movement’s efforts to protect Tamil and English as the primary languages of education and administration.

Since then, Tamil Nadu’s Dravidian governments have championed education in both Tamil and English, significantly contributing to the state’s development.

Anandhi noted that today, Tamil Nadu boasts one of the highest higher-education enrolment rates in India, a testament to the success of this linguistic policy.

Gandhi added another layer to this ideological debate by emphasising the role of Hindi in maintaining control. He asserted that English can no longer be viewed as a tool for domination, as there is no intention to use it to rule over Tamil Nadu. Gandhi said that there is no cultural imposition through English; it does not carry the same political weight as Hindi.

However, he highlighted that Hindi is intrinsically linked to power, and this power is tied to specific social groups that view marginalised communities as inferior and underscored that these groups seek to impose their will upon the people of Tamil Nadu through the imposition of Hindi, using language as a tool of control.

He further argued that Hindi is an unsuitable language for competitive examinations, noting that no matter how much one learns the language, it will always put non-native speakers at a disadvantage. Gandhi pointed out that this creates a systemic barrier that ensures those who speak Hindi as their mother tongue will always have an upper hand in examinations and public life.

Through this ideological war, the Dravidian movement has shaped Tamil Nadu’s political and educational landscape, ensuring that language remains not only a medium of communication but also a tool for social empowerment and progress. he said.

Anandhi explained that by prioritising education in Tamil and English, the Dravidian movement ensured that Tamil Nadu continues to thrive in terms of education and social mobility while resisting external linguistic impositions that threaten its social fabric.

This linguistic strategy has not only contributed to the state’s intellectual development but has also played a crucial role in its broader human development, she added.

(Edited by Muhammed Fazil.)