Published Oct 21, 2025 | 11:00 AM ⚊ Updated Dec 01, 2025 | 8:32 AM

Kerala, which had resisted NEP 2020 on ideological and federal grounds, faced the withholding of funds crucial for running its schools.

Synopsis: One of the fiercest critics of the Union government’s NEP 2020, the CPI(M)-led LDF government’s recent U-turn over its two-year-long boycott of the PM SHRI scheme has ignited tensions within the ruling coalition in Kerala. Alliance partner CPI has criticised the decision as “politically flawed and fiscally insignificant,” while the opposition has cornered the CPI(M) over political hypocrisy. The stark reality is that the state reversed its boycott to secure the release of nearly ₹1,500 crore in withheld funds.

Barely three and a half months ago, Kerala Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan warned that the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 “poses a danger to the country,” accusing the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government at the Centre of enforcing it “at the behest of the RSS [Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh].”

Then, General Education Minister V Sivankutty echoed this hard line, making it clear that Kerala would not be a signatory to the Prime Minister’s Schools for Raising India (PM-SHRI) scheme, which mandates the implementation of NEP.

But in a dramatic U-turn, on Sunday, 19 October, the same Communist Party of India (Marxist) [CPI(M)]-led Left Democratic Front (LDF) government decided to sign up for PM SHRI—now an integral part of NEP—without even a cabinet discussion or consultation with its alliance partners.

The move has left the front divided, giving the Congress an opportunity to attack the CPI(M) for what it calls “political hypocrisy.”

For a government that once positioned itself as one of NEP’s strongest critics, the dice has clearly turned. In the days ahead, the CPI(M) will have to do more than explain a policy shift—it will have to navigate the political storm brewing both within the Left camp and outside it.

The stark reality is that the state reversed its two-year-long boycott of the PM SHRI scheme, eyeing the release of nearly ₹1,500 crore in withheld funds.

The decision marks a striking shift in the LDF government’s position, reflecting the tension between ideological resistance to NEP 2020 and the fiscal needs of a cash-strapped state.

It is a revealing case study in Indian federalism—how states balance political autonomy with economic necessity.

Launched in 2022, PM SHRI is a flagship initiative of the Union Ministry of Education to upgrade over 14,500 existing schools across India into model institutions reflecting the principles of NEP 2020.

These schools are envisioned with smart classrooms, digital libraries, sports facilities, and skill-based learning programs.

The scheme functions as a Centrally Sponsored Scheme (CSS), with a total outlay of ₹27,360 crore between 2022 and 2027. The Centre contributes ₹18,128 crore, while states provide the rest.

Typically, two schools are chosen per block or taluka, each receiving around ₹1 crore annually for infrastructure development. In Kerala, 336 schools are expected to be covered.

Yet, according to the PM SHRI dashboard, only 47 schools—33 Kendriya Vidyalayas and 14 Jawahar Navodaya Vidyalayas—had joined the scheme, leaving state-run schools out of the loop.

Kerala’s resistance to PM SHRI was rooted in its opposition to NEP 2020, which the LDF government accused of “saffronizing” education, promoting corporatization, and eroding scientific and secular values.

The state saw PM SHRI as an indirect route to force NEP implementation, undermining state autonomy in education, a subject on the Concurrent List of the Constitution.

Concerns also focused on curriculum changes, such as deletions from history textbooks, and the mandatory display of “PM SHRI School” signboards, seen as symbolic of central overreach.

This confrontation intensified when the Union government withheld around ₹1,500 crore under related schemes, including the Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA), affecting Kerala’s already strained education finances and delaying salaries for thousands of teachers and staff.

Two replies in Parliament show how the Union government effectively pressured the state into signing the PM SHRI MoU by linking it to crucial allocations under the Samagra Shiksha scheme.

They reveal how the Centre leveraged education funds to bring Kerala in line with PM SHRI, a key vehicle for implementing NEP 2020.

In a written reply to MP Hibi Eden in the Lok Sabha in December 2024, Minister of State for Education Jayant Chaudhary said ₹697.31 crore had been approved for Kerala under Samagra Shiksha for 2024–25.

This figure was later revised to ₹855.90 crore after including reimbursements and spill-over amounts.

However, the Minister clarified that no funds could be released because the state had not signed the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) for the PM SHRI scheme, launched in September 2022 to develop over 14,500 NEP 2020 exemplar schools across the country.

“Every State/UT is required to sign a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the Ministry of Education and so far, 33 States/UTs have signed the MoU… The State of Kerala is yet to sign MoU for PM SHRI scheme with the Ministry, therefore, no funds could be released,” the Minister said.

The government made clear that the alignment of Samagra Shiksha—an integrated scheme covering pre-school to Class XII since 2018–19—with NEP 2020 is mandatory.

PM SHRI schools, the Minister said, were designed to “function as NEP 2020 exemplar schools.”

This was reinforced seven months later, in July 2025, when MP John Brittas raised a similar question in the Rajya Sabha.

Responding to whether funds had been withheld under Samagra Shiksha due to Kerala’s refusal to sign the PM SHRI MoU, Minister Jayant Chaudhary said funds are released only after fulfilling the conditions prescribed by the Ministry of Finance.

He underlined that Samagra Shiksha has been aligned with NEP 2020, and PM SHRI schools are intended to “showcase the implementation of NEP 2020 and offer leadership to other schools.”

Out of 36 States and UTs, 33 have signed the MoU. Kerala remains among the three holdouts, despite what the Minister described as “requests and reminders at the level of Secretary and Union Minister.”

“Since the state of Kerala is implementing Samagra Shiksha Scheme which has been aligned with NEP 2020, it would be appropriate that the States come forward to implement and showcase all the initiatives of NEP 2020 including under PM SHRI Scheme,” the Minister noted.

This chain of replies shows how the Centre bundled financial assistance under an ongoing education programme with compliance to its flagship policy – NEP 2020.

Kerala, which had resisted NEP 2020 on ideological and federal grounds, faced the withholding of funds crucial for running its schools.

Between 2022 and 2026, the Centre had proposed ₹1,53,855.99 lakh for Kerala under Samagra Shiksha, but the release of funds depended on the MoU.

Effectively, the Centre turned alignment with NEP 2020—once a policy choice—into a funding condition, leaving Kerala little room to manoeuvre.

The PM SHRI decision also exposes Kerala’s fiscal constraints.

When LDF convenor T.P. Ramakrishnan was asked on 20 October why the state is not challenging the scheme in the Supreme Court like Tamil Nadu, he said that while the neighbouring state has ample revenue, Kerala does not have the financial bandwidth.

When the Union government unveiled NEP 2020, Kerala rejected its core elements, continuing with its own curriculum and opposing what it saw as attempts at centralization.

When a delegation from the state General Education Department met the Ministry of Education officials in May at New Delhi.

Kerala, along with Tamil Nadu and West Bengal, refused to sign the required MoU, fearing that participation would lock it into NEP compliance. Over the next two years, fund flows from the Centre under SSA and other programs were curtailed, deepening the state’s financial crunch.

By 2024, internal discussions began within the LDF. While the CPI(M) signaled a willingness to reconsider, its ally CPI remained firm in opposition.

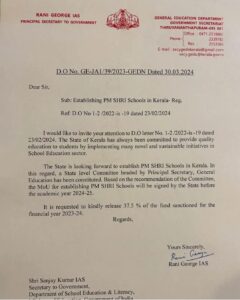

In March 2024, then Principal Secretary (General Education) Rani George IAS wrote to the Union Education Secretary, expressing Kerala’s readiness to sign the MoU before the 2024–25 academic year.

The Centre welcomed the move, calling it a “far-reaching decision” to strengthen education and federal cooperation.

On 26 June 2025, Education Minister V. Sivankutty announced that Kerala would not sign the MoU, citing adherence to the LDF manifesto.

The state prepared to challenge the Centre in the Supreme Court, arguing that withholding funds amounted to coercion in violation of constitutional norms.

Amid persistent financial strain, Sivankutty held talks with Union Education Minister Dharmendra Pradhan. This opened the door for renewed discussions between the state leadership and the CPI(M).

In a move that surprised even coalition partners, Sivankutty announced Kerala’s decision to sign the MoU, directing the department secretary to proceed without cabinet approval.

The state justified the shift as a “pragmatic decision” to unlock withheld funds, but it triggered criticism from opposition parties, student groups, and even within the ruling front.

The Centre maintained that PM SHRI was essential for achieving educational equity and implementing NEP, and that withholding funds was merely a mechanism to ensure scheme alignment. The LDF saw it differently, framing it as federal coercion and an attack on state rights.

For Kerala, the conflict was more than ideological: it became an economic standoff. With the scheme set to expire in 2026–27 and no retrospective funding available, the state faced a choice between ideological purity and practical necessity.

Kerala’s core dilemma lies in the conditions embedded in the PM SHRI MoU.

The first condition mandates that states implement NEP 2020 in its entirety. This directly contradicts the LDF’s position, which has consistently rejected NEP’s ideological and structural framework.

The second condition requires that all participating schools bear the PM SHRI prefix, something the state previously opposed as political branding of public education.

A letter from the state Principal Secretary (General Education) in 2024 expressing state’s wish to become part of PM SHRI.

By signing the MoU, Kerala is legally bound to these terms, making its earlier assurances of “selective implementation” difficult to sustain. How the state navigates these conditions—especially with elections around the corner—remains a major political question.

The Kerala government has tried to frame its decision as fiscal pragmatism, arguing that the funds are essential for modernising schools, building hostels, and ensuring teacher salaries. Yet, this has exposed cracks within the ruling coalition and invited attacks from opposition parties, who accuse the LDF of ideological inconsistency.

Kerala’s PM SHRI volte-face sets the stage for intense political and legal debates. If the state tries to circumvent NEP implementation, it may face future conflicts with the Centre. If it complies, it risks alienating parts of its ideological base.

With the clock ticking toward the 2026–27 scheme deadline and state elections looming, Kerala’s handling of PM SHRI will likely become a defining test of the LDF’s governance model, where ideological resistance meets the hard arithmetic of finances.

The state’s sudden decision to sign the MoU with the Union government to access PM SHRI funds has set off a political storm, exposing fault lines within the ruling LDF.

The Communist Party of India (CPI), a key LDF ally, immediately struck a defiant note.

Party state secretary Binoy Viswam slammed the move as “politically flawed and fiscally insignificant,” warning it could be read as an endorsement of the Sangh Parivar’s “saffronisation of education.”

CPI ministers are expected to register their protest in the next Cabinet meeting. Its student wing, the All India Students’ Federation, also voiced strong opposition, while the CPI mouthpiece Janayugom carried an article cautioning against “losing control of public education to a central agency.”

The CPI fears that PM SHRI would create two classes of government schools and undermine Kerala’s secular educational model, painstakingly built through massive state investments.

In contrast, CPI(M) leaders and the Education Minister maintain that the funds are Kerala’s right and should not be forfeited on “technicalities,” especially when other departments like Health, Agriculture, and Higher Education already benefit from Central schemes.

The Opposition was quick to capitalise.

Kerala Pradesh Congress Committee (KPCC) president Sunny Joseph accused the CPI of “empty sabre-rattling” and mocked the CPI(M)-BJP “understanding.” BJP state president Rajeev Chandrasekhar called it “belated wisdom” and demanded an apology for “denying students modern facilities for two years.”

Kerala’s decision to finally embrace PM SHRI will have to be considered more than just a policy shift – it is a political tightrope walk.

What began as a battle over ideology has ended in a calculated compromise, with the state conceding ground, as it claims, to secure its share of central funds.

But in doing so, the LDF has set the stage for a storm that could reshape its own political equations. How the government balances its ideological stance with the fine print of NEP 2020—under the glare of both allies and adversaries—will determine whether this is remembered as a pragmatic course correction or a retreat under pressure.

(Edited by Dese Gowda)