Published Jan 17, 2025 | 9:00 AM ⚊ Updated Jan 17, 2025 | 9:00 AM

Officials in front of the Living Will Information Counter

In a groundbreaking move championing the right to die with dignity, the Government Medical College Hospital (GMCH) in Kollam, Kerala, has launched India’s first Living Will Information Counter near its outpatient block.

Despite the Supreme Court’s historic 2018 ruling and simplified 2023 guidelines on living wills, this crucial healthcare concept remains largely misunderstood and underutilised.

With this initiative, the GMCH aims to spark a much-needed conversation about living wills, highlighting how straightforward their execution can be and the profound impact they often may have.

Also read: Why are more children experiencing sudden heart-related deaths?

A living will is a legal document that specifies an individual’s preferences for medical care if they become incapacitated and unable to make decisions, such as during a terminal illness, while comatose, or in advanced dementia.

It enables individuals to exercise autonomy over their healthcare, ensuring they receive the treatment they desire while sparing loved ones the burden of making difficult decisions.

In India, the concept of a living will received legal recognition through landmark Supreme Court judgments. The Aruna Shanbaug case (2011) legalised passive euthanasia, deriving the right to die with dignity from Article 21 of the Constitution.

This principle was expanded in the Common Cause v. Union of India judgment (2018), which affirmed the legality of living wills as an extension of individual autonomy and self-determination.

A living will

Initially, drafting such directives was complex, but the process was simplified on 23 January 2023, requiring certification by a gazetted officer or notary and two witnesses to ensure voluntariness.

Living wills provide clarity and dignity in end-of-life care, safeguarding individuals’ wishes while reducing stress and moral dilemmas for caregivers during critical moments. While often associated with older adults, a living will is essential for anyone to prepare, as unexpected medical crises can occur at any age.

Anyone over the age of 18 can execute a living will. It must be a written document with at least two designated Healthcare Power of Attorneys (or more, if desired) and two witnesses.

Previously, it required countersigning by a judicial magistrate; however, it can now be attested by a notary or gazetted officer, provided they are satisfied that it has been executed voluntarily, without coercion, and with full understanding.

The executor is also expected to share copies with the Healthcare Power of Attorneys, family physician or chosen doctor, and the competent officer of the local body where they reside.

The Living Will Information Counter at GMCH was inaugurated on 1 November, 2024 on occasion of Kerala Piravi Day. Within a short period, it has witnessed a steady flow of inquiries, with over 100 people seeking information and assistance to understand the process.

The counter provides comprehensive details about living wills in both English and Malayalam.

GMCH, Kollam

According to Dr IP Yadav, nodal officer of the Model Palliative Care Division at GMCH, volunteers associated with the initiative have extended their efforts beyond the counter by conducting grassroots awareness campaigns.

“They conduct community sessions in libraries, resident associations, and other local venues every week, making the concept of living wills familiar even in remote areas.

“While the counter officially opened in November 2024, the groundwork for this movement began as early as March 2023. We are committed to spreading knowledge and creating a robust support system,” Yadav told South First.

The counter has also attracted interest from other hospitals, which often seek guidance on replicating the model.

To simplify the process, the team translated the Vidhi Foundation’s living will form into Malayalam, ensuring that people from all linguistic backgrounds can understand and complete it independently.

Also read: Which surgery brings the Highest Infection Rate? ICMR study has the answer

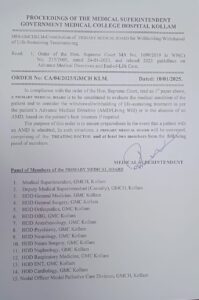

One of the key milestones achieved by the initiative, according to Dr Yadav, is the establishment of a Primary Medical Board, a prerequisite set by the Supreme Court for implementing living wills.

Constitution of primary medical board

This board comprises the treating doctor and two subject-matter experts with a minimum of five years’ experience. It evaluates a patient’s medical condition to determine the appropriateness of withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining treatments.

The board ensures that such decisions are made with both medical and ethical precision.

Also read: Why are experts frowning at the name of a skin fungus linked to India?

Volunteers associated with GMCH’s living will awareness initiative have highlighted the personal experiences shared by those who have opted for living wills.

Many recount the trauma of seeing loved ones suffer due to decisions made in the absence of clear guidance. Dr Yadav himself shared an example from his own life, deeply regretting his decision to place his father on a ventilator against his wishes.

Despite his father explicitly requesting not to be subjected to life-sustaining measures, Dr Yadav, driven by an instinct to prolong his father’s life, made a choice that left him carrying a heavy emotional burden.

Conversely, the counter has also encountered cases where individuals specify unique preferences in their living wills. One elderly man insisted on being placed on a ventilator, explaining that he wanted to wait for his son, who lived abroad, to see him one last time.

“The movement has gained momentum through collective action, with inspiring examples of entire families engaging in the process,” said Dr Yadav.

He shared a notable instance where 65 members of an extended family, aged between 18 and 85, attended multiple sessions to write their living wills together. “This act not only fostered awareness but also created a sense of shared responsibility and understanding within the family,” he added.

Interestingly, the counter has observed that the initiative appeals primarily to two distinct groups: educated senior citizens and individuals from economically and socially disadvantaged backgrounds.

Middle-aged individuals, aged 40–50, are also increasingly showing interest, often motivated by personal experiences of witnessing suffering or trauma in hospitals.

According to volunteers, the first step in raising awareness is educating people about the difference between a living will and a normal will.

“We make them understand that a living will is a legal document specifying an individual’s preferences for medical treatment if they become terminally ill or incapacitated and cannot communicate their wishes,” explained a volunteer. “It ensures that a person’s decisions regarding life-sustaining treatments, such as ventilators or feeding tubes, are respected, particularly in cases like vegetative states or terminal illnesses.”

In contrast, a normal will is a legal document that specifies how an individual’s assets, property, and belongings are to be distributed after their death. It ensures that the deceased’s wishes regarding the distribution of their estate are carried out, minimising disputes among heirs.

People interested in executing a living will are also informed that they can include instructions regarding what should be done with their body post-death. “This section is entirely optional. But one can clearly state whether their body parts could be used for organ donation, whether their body could be handed over for the purpose of medical research and education and even wishes pertaining to last rites/funerals specifying whether to follow any religious rituals or not upon their death,” said a volunteer.

Dr.B.Padmakumar, Principal, GMC Kollam signing his Living Will

The volunteers highlighted the importance of this section by citing the dispute over the mortal remains of CPI(M) leader MM Lawrence.

A legal battle erupted between his children regarding his body’s donation to the Government Medical College, Ernakulam, for research purposes.

While two of his children claimed that Lawrence wished to donate his body for research, his daughter insisted on burying him alongside her mother.

“Had he executed a living will by stating what to do with his body post-death such legal dispute could be avoided. However, that incident had once again reignited the discussion on the importance of living will,” said a volunteer.

Also read: Breath of hope: How technology is transforming lung health

“The difference between a living will and euthanasia often leaves people puzzled,” says Dr Yadav.

Euthanasia involves intentionally ending a person’s life to alleviate unbearable suffering. It is divided into two categories: passive euthanasia, which allows death by withdrawing or withholding treatment, and active euthanasia, which involves directly taking steps to end life.

Dr Yadav highlights a common misconception: many people equate a living will with passive euthanasia. “But the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) has clarified this in its 2018 document titled Definition of Terms Used in Limitation of Treatment and Providing Palliative Care at the End of Life, released shortly after the Supreme Court allowed passive euthanasia in cases involving living wills,” he explains.

The ICMR considers the term “passive euthanasia” misleading and advocates for using “withholding or withdrawing futile treatment” instead. “The term ‘passive euthanasia’ might imply an intention to kill, which is not the case,” Dr Yadav points out.

The document emphasises that the focus should be on limiting futile treatment – care that merely prolongs the dying process without improving quality of life. “We don’t support an intention to kill. Adopting a more neutral term like ‘withholding or withdrawing treatment’ encourages informed public discussions on this sensitive issue,” the document states.

Also read: Elderly cancer patient’s suicide exposes hollow insurance promises

Dr MR Rajagopal, Padma Shri awardee and a staunch advocate of living wills, believes that mere awareness isn’t enough to bridge the gap between understanding and implementation. Speaking to South First, the founder of Pallium India emphasised:

“It’s not just about knowing what a living will is. On the ground, there’s a glaring disparity between knowledge and practice. What we need is widespread public awareness – people must understand what a living will is and how it can transform end-of-life care. The state government and other organisations must take the lead in creating this mass-scale awareness.”

In contrast, a senior health department official highlighted the ethical dilemma faced by medical practitioners in Kerala. “Our society must question whether medical professionals should prolong life at all costs – stretching death by hours or days – even when treatment has become futile,” the official stated.

Kerala’s unique context adds urgency to this debate. “In this state, the majority of patients with incurable critical illnesses die on life support systems – often isolated in the ICU. This reflects a deeper issue: we are largely ‘death-illiterate.’ We need death literacy to embrace these conversations openly and bravely,” the official added.

(Edited by Dese Gowda)