Published Nov 12, 2024 | 9:00 AM ⚊ Updated Nov 14, 2024 | 12:43 PM

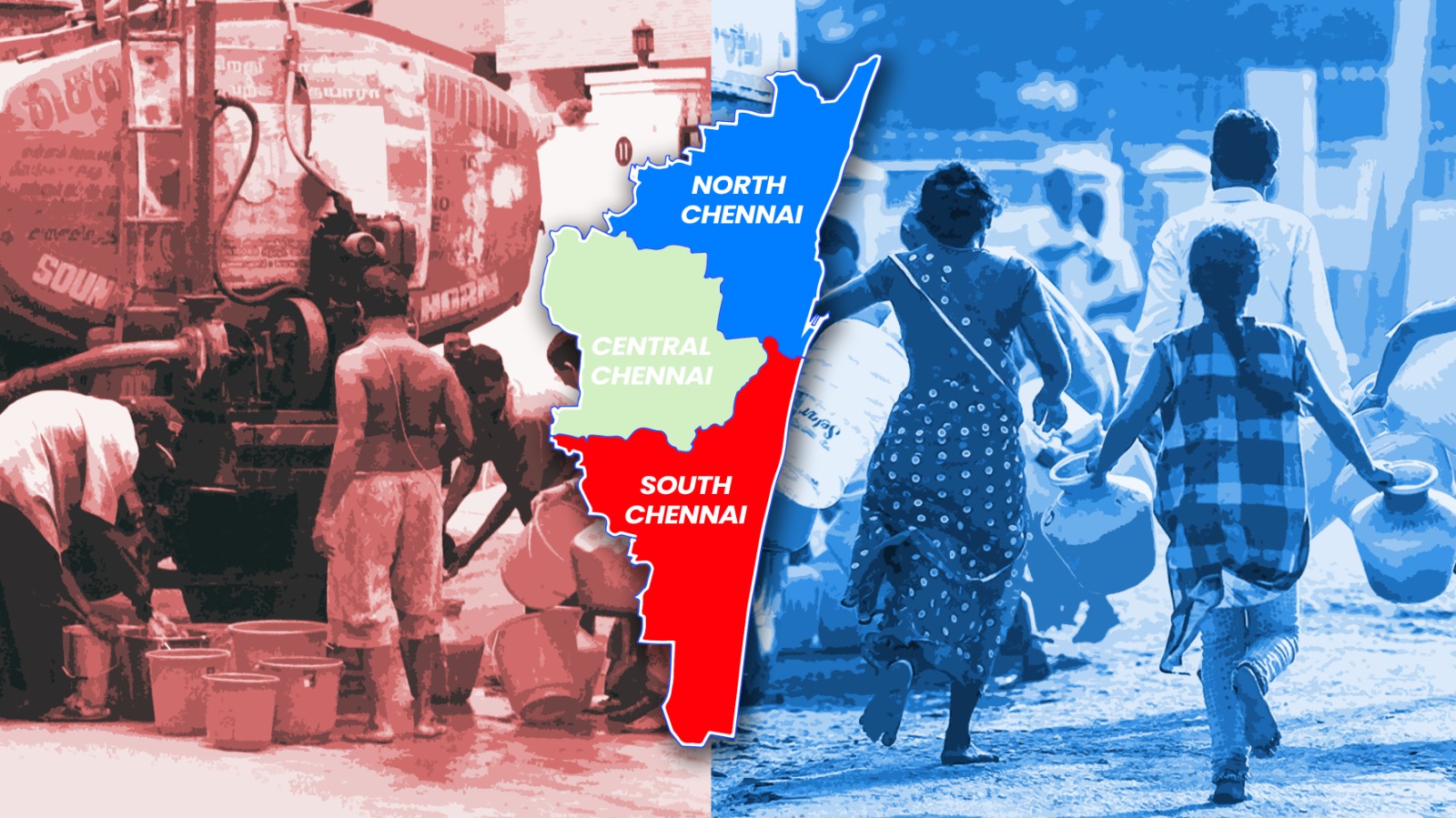

North Chennai waits for water, South Chennai filters and pays.

“In North Chennai, clean water feels like a distant dream,” says Shalin Maria Lawrence, a resident and Dalit activist.

“I grew up drinking water from pipes that often carried sewage. Every drop we get is uncertain — sometimes murky, often with a foul smell. Many of us have got used to living with illnesses. It is especially worrying as the children are forced to drink the foul water too, when their immune systems are fragile. Typhoid and stomach infections have become common in our community, clean water is so scarce,” Lawrence tells South First.

“Our pleas fall on deaf ears,” she adds. “We live in one of the biggest cities in the country, yet every glass of water is a gamble with our health. When will we finally be seen and heard?”

Residents from neighbourhoods like Vyasarpadi, Pattalam, and Nehru Nagar echo similar sentiments, asking when North Chennai’s persistent water crisis will be treated with urgency.

There are roads where a constant stench of sewage from the pipelines hangs in the air.

Selvan (name changed), a stall owner, tells South First, “Most people don’t know how bad it is here. The water supply is inconsistent, and when it finally comes, it’s often brown or smells like chemicals. We use whatever little clean water we get for cooking and drinking. For washing or bathing, we have no choice but to use the contaminated supply. It’s been like this for years, and we keep hearing that things will improve, but nothing changes. I’ve started feeling that North Chennai is simply ignored.”

Shanti, another resident from North Chennai adds, “I’ve been here my whole life. Things haven’t changed. My grandchildren have skin issues because they bathe in this water, but we don’t have a choice. Sometimes, I boil the water for them, but that doesn’t take away the chemicals. We need the pipes to be fixed properly, the temporary fixes are useless.”

Priya (name changed) tells South First, “It’s not just the water – it’s the sense that we’re left behind in every way. My college friends from other areas don’t have to worry about dirty water or power outages. I feel embarrassed to bring friends home. The water is just one issue. It represents the neglect of our area. We need basic facilities. It is tiring to keep asking for basic rights like access to clean water.”

While the residents of North Chennai contend with irregular water supply and contaminated water in their piped supply, residents of neighbourhoods like Anna Nagar, T Nagar, and Royapettah face a different reality.

Although water availability is better, these residents still have concerns about water quality. They pay additionally for clean drinking water and filtration systems.

“In Annanagar, we do get corporation water, but it is usually only suitable for washing and bathing,” Arvind, a software engineer, told South First. “For drinking, we rely on bottled water. It’s an expense, but at least we don’t have to worry about getting sick.”

In T Nagar, where many residents live in apartment complexes, Shalini, a marketing executive, tells South First, “We’ve had instances where the tap water looked cloudy. We invested in a water purifier to stay safe, but these things add up.”

Kavitha (name changed), a retired music teacher from Annanagar, shares a similar sentiment. “The water supply is fairly consistent, but during certain months, the quality deteriorates, likely due to poor groundwater quality. Most of us here have filters installed, but even those don’t completely eliminate the salinity. We end up buying water when needed, especially for cooking and drinking,” she says.

In Royapettah, Siddharth (name changed), a small textile business owner, explains, “People here don’t feel the crisis North Chennai faces, but it is still not an ideal situation. There is a general preference for bottled or purified water for drinking, even though the corporation water is enough for other uses. I know some families who have to budget just for water expenses.”

Chennai’s water is primarily sourced from four reservoirs: Poondi, Cholavaram, Red Hills, and Chembarambakkam, supplemented by desalination plants at Minjur and Nemmeli.

According to the Chennai Metropolitan Water Supply and Sewerage Board (CMWSSB), these desalination plants contribute up to 126 Mega Litres per Day (MLD), a necessary but insufficient supplement to natural reservoirs, which depend on rainfall.

With rainfall patterns becoming more unpredictable, the reliance on desalination has increased.

Additionally, Chennai’s groundwater extraction and borewell usage are widespread, but excessive use over the years has resulted in falling groundwater levels, exacerbating the demand-supply gap.

“As per GoI’s [Government of India] mandate, Chennai is accorded 12 TMC of drinking water annually based on water availability from River Krishna. However, we haven’t released as much due to the variability of Krishna water flow after it passes through Maharashtra and Telangana,” says MV Ramana Reddy, Superintendent Engineer of the Somasila Link Canal in Andhra Pradesh, told South First.

“On average, we release no less than 5 TMC a year, with peak releases reaching 8.443 TMC in 2010-2011 and 8.097 TMC in 2020-2021,” he says.

In recent years, Chennai has received additional water from Andhra Pradesh’s Krishna River through the Kandaleru reservoir.

This inter-state water transfer, governed by a federal mandate, allows for up to 12 TMC (thousand million cubic feet) of water annually, though the actual amount varies based on availability.

City water supply and infrastructure development

Chennai’s Master Plan, initially updated in 1991, underwent revisions in 1997. This updated plan projected water requirements and allocations for Chennai’s main areas, accommodating population growth and expanding industries.

By 2021, Chennai City itself required an estimated 942 million litres per day (MLD), with nearby urban areas and special industrial zones adding significant demand.

To improve water distribution, Chennai was organised into 16 zones. Twelve new water distribution stations were constructed, and 11 existing ones were upgraded. Leak detection efforts, the replacement of 585 km of old pipelines, and the renewal of about 195,000 house connections were undertaken to enhance water conservation and supply reliability.

New transmission mains, stretching 36 km, were also laid to connect water sources to distribution stations, improving coverage and efficiency.

New technologies like Geographic Information System (GIS) mapping and Information System Technology Planning (ISTP) were piloted for better system management.

Additionally, a study of the Araniar-Kosathalaiyar River Basin confirmed the possibility of extracting up to 100 million cubic meters (mcm) of groundwater annually in normal years, or 70 mcm during droughts, to supplement supply.

The Veeranam Water Supply Project, launched in 2004, brought 180 MLD of water from Veeranam Lake to Chennai. This lake is fed by the Cauvery River system as well as local rainwater.

Water is pumped over 200 km through a system of large-diameter pipes, treated, and then transported to Porur Distribution Station for distribution throughout the city.

Desalination plants:

Two desalination plants have been set up to address Chennai’s coastal water challenges:

– The Minjur Plant (established in 2010) provides 100 MLD of desalinated water.

– The Nemmeli Plant also supplies an additional 100 MLD, bolstering the city’s water resources.

Current water treatment capacity:

With the various water sources and treatment facilities now in place, Chennai’s total water treatment capacity reaches approximately 1,494 MLD.

Key treatment plants include:

– Kilpauk (270 MLD)

– Puzhal (300 MLD)

– Vadakuthu (Veeranam Lake) (180 MLD)

– Chembarambakkam (530 MLD)

– Surapet (14 MLD)

– Minjur Desalination (100 MLD)

– Nemmeli Desalination (100 MLD)

“Yes, we acknowledge the supply challenges in North Chennai and are fully aware of the difficulties residents face,” Sivamurugan, Chief Engineer of the Water Supply Board of Chennai, told South First, “To address this, we’ve ramped up water deliveries by deploying additional tankers to the area.”

“The infrastructure in North Chennai is quite dated, which unfortunately sometimes results in contamination as water passes through ageing pipes. However, we’re actively working on a comprehensive upgrade, and within the next year, we expect a significant improvement in both the quality and reliability of the water supply,” he adds.

Sivamurugan also reassured residents citywide. “We’re doing everything possible to manage water distribution across Chennai, and the situation is largely under control. We’re carefully balancing the city’s growing demand while modernising the system where needed, and we ask for patience as we work toward providing clean, dependable water for all.”

(Inputs from Saicharan Sana. Edited by Rosamma Thomas).