Published Nov 28, 2024 | 9:00 AM ⚊ Updated Nov 28, 2024 | 9:00 AM

Organ Donors. (Representative Image)

The grim statistic that nearly 2,000 patients had died waiting for organ transplant, shared by the Kerala State Organ and Tissue Transplant Organisation (K-SOTTO), has reignited debate over the state’s faltering cadaver organ donation programme.

India sees the third-largest number of organ transplants in the world, after the United States and China. In India, though, less than one person per 10 lakh population is the rate of deceased donation of organs. That makes for a huge difference between the need and availability of organs.

Over the past 12 years, 1,870 individuals in Kerala have died waiting for organ transplant. Kerala is often celebrated for its healthcare achievements; yet, it ranks a dismal 13th in organ donation nationwide, far behind Rajasthan, which leads the list.

The state has also seen scams related to organ donation, with money exchanged for organs, and procedures being conducted in institutions not authorised to perform such procedures.

A campaign poster.

In 2020, state police launched a probe after several kidney donors were found in a locality in Thrissur; the donations were made to people in other parts of the state, even though the donors seemed unacquainted with the recipients.

In May this year, a man who travelled from Iran was arrested at the Kochi International Airport for trafficking people for organ sale – Iran is the only country in the world that allows the legal sale of kidneys.

The concern over the huge gap between the need and availability of organs for transplant in Kerala has led K-SOTTO to launch a fresh awareness campaign titled “Let Your Light Shine on Others.”

The initiative is to encourage more people to pledge their organs after death while addressing misconceptions about organ donation that have stifled progress.

Despite these efforts, the road ahead is fraught with challenges, from public distrust to systemic inequalities in organ allocation.

The stark reality of deaths of patients awaiting organ transplant was examined in a study, published in ‘Transplantation’, the official journal of The Transplantation Society, based in the UK.

Funded by the State Health System Resource Centre, Government of Kerala, the study examined the state’s cadaveric organ donation programme.

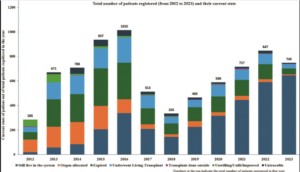

It found that since Kerala’s deceased organ donor programme began in 2012, a total of 7,830 patients have registered for transplant.

Patients registered and their current status

However, only 367 deceased donations were recorded, leading to the retrieval of just 1,024 organs — an average of 2.8 organs per donor.

This means only about 13% of registered patients received cadaveric organ transplants. The study shows that about 1,900 patients died waiting.

Alarmingly, 1,000 patients have been on the waiting list for over five years.

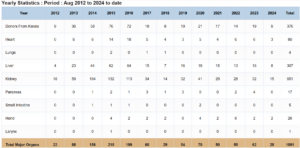

Over two-thirds of transplant candidates are kidney patients, followed by 31% awaiting liver transplants, while heart, lung, pancreas, and small intestine recipients make up the remaining 3%.

Adding to the inequity, a staggering 99% of organs other than kidneys are allocated to private hospitals, with public hospitals receiving only 24% of harvested organs. Few government institutions even perform transplants.

This allocation imbalance has fuelled public scepticism and mistrust of the system.

The study says that the donation rate in Kerala began to decline significantly after 2017.

It attributes this to two key events:

– A 2016 public interest litigation alleging malpractice in brain-death certification.

– The release of a 2018 Malayalam movie, Joseph, which depicted organ donation in a negative light.

The study opined that such narratives have sown mistrust among the public.

Many believe brain-death declarations are manipulated for organ retrieval, with comments like “How can I be sure that what was shown in the movie isn’t true?” resonating widely.

At the same time, one of the co-authors of the study cited reasons like reluctance of doctors, government apathy and legal hurdles, systemic challenges, inconsistent practices and other causes for the low cadaver organ donation numbers.

“ICU doctors and neurologists, crucial for certifying brain death, have become wary due to social media backlash, police complaints, and litigation. Fear of being accused of malpractice has led many to refrain from active participation in organ donation programmes,” said a co-author.

Healthcare providers also cite a lack of government support, leaving them to navigate legal challenges on their own.

Hospitals also shy away from promoting organ donation, fearing bad publicity.

Another controversy being cited is disparity in organ allocation as private hospitals dominate both organ donation and transplantation.

Under current policies, donor hospitals retain priority access to organs, further skewing equity.

Kerala Deceased Donor Transplant Data

Those who worked on the study found that interviews with clinicians revealed widespread inconsistency in brain-death certification and organ donation protocols.

Even when brain death is confirmed, some patients remain on ventilators indefinitely if organ donation is not pursued.

“Health care providers are not yet convinced that brain death is death. There are clinicians who took the view that life support cannot be withdrawn even if the patient is certified brain stem death,” said the co-author.

Brain death, also known as brain stem death, occurs when a person on artificial life support has permanently lost all brain function.

This means the patient will never regain consciousness or breathe independently. Once brain death is confirmed, it is legally recognised as death.

Recovery is impossible, as the body can no longer sustain itself without artificial support.

Experts point out that to address public scepticism, there is a pressing need to separate brain-death certification from organ donation decisions.

Intensive care specialists must be empowered to confirm brain death independently, using clear neurological criteria.

Also, a revision of the Registration of Births and Deaths Act and the Uniform Definition of Death Act (UDDA) is being demanded as it is vital to establish a transparent framework.

Another aspect is stronger regulatory oversight to ensure fairness in organ allocation between private and public hospitals.

Both sectors must be held equally accountable for donations and transplants.

A person who pledged his organs following the campaign

As Kerala’s organ donation programme, once a beacon of hope, now stands at a crossroads, K-SOTTO’s initiative to dispel myths and inspire public participation is a step in the right direction.

However, voluntary organisations could also amplify efforts to educate communities about the life-saving potential of organ donation.

The state must urgently address public mistrust, streamline brain-death certifications, and enforce equitable policies.

K-SOTTO statistics show that even though Kerala has a population of about 3.5 crore, only 2,937 have pledged their organs after death.

It’s time to let the light of hope shine brighter.

(Edited by Rosamma Thomas)