Published Sep 16, 2025 | 9:00 AM ⚊ Updated Sep 26, 2025 | 11:47 AM

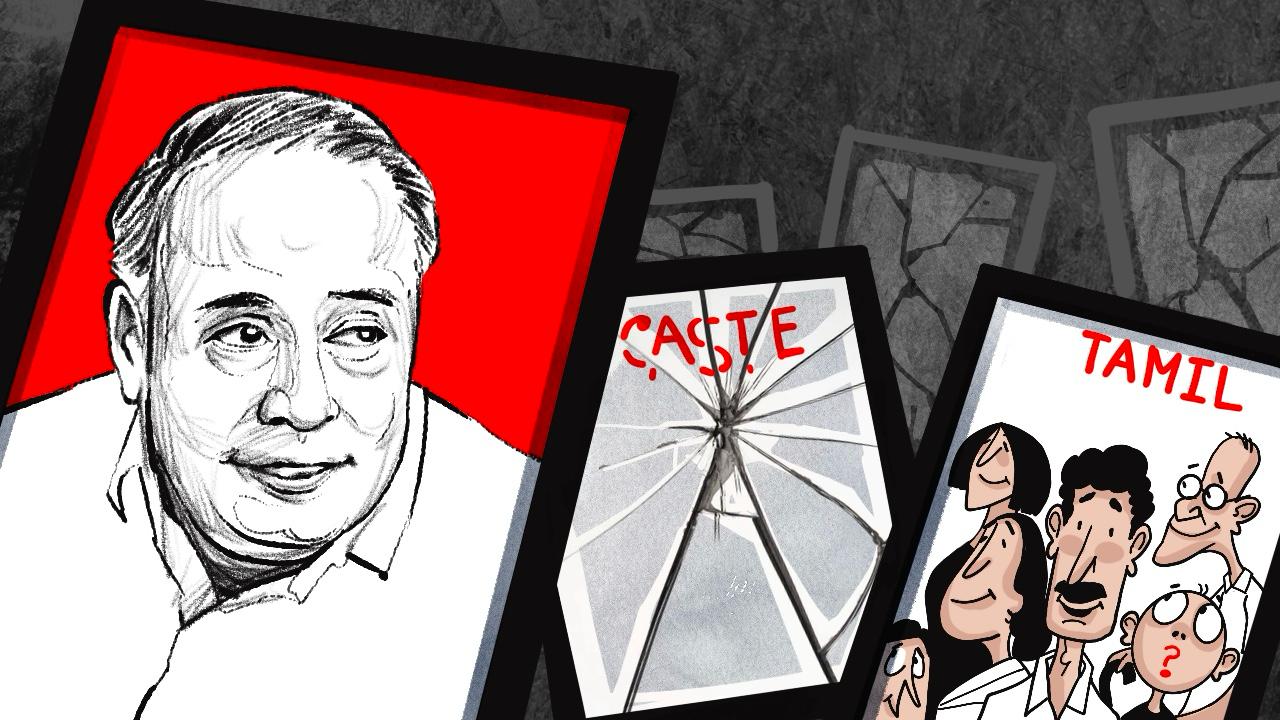

Has Anna’s vision survived?

Synopsis: The DMK in Tamil Nadu is preparing to celebrate its 76th anniversary. Has the DMK remained true to the founding principles Annadurai set? What path has it travelled, and how have its ideologies evolved? A re-examination becomes necessary.

On the evening of 18 September 1949, torrential rains lashed Chennai. Thunder, lightning, and downpours filled the skies. Yet, another sound that cut through the roar of the storm was the one that drew the attention of all of Tamil Nadu. At Robinson Park in Chennai, under the leadership of former chief minister CN Annadurai, the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) was formally launched.

Standing before a crowd that refused to disperse despite the relentless rains, Annadurai — fondly remembered as Anna — declared that the DMK would remain steadfast in the principles of Periyar and would pursue three core ideologies: Social reform, economic equality, and liberation from northern domination in politics.

Since that evening, 76 years have passed, and today the DMK is preparing to celebrate its founding anniversary.

Adding to its anniversary, the DMK-governed Tamil Nadu now stands as the only state in India to have double-digit economic growth, at 11.19 percent. It is also the state that has consistently resisted authoritarian centralisation, defended federalism through political battles and legal challenges, and today ranks among India’s leaders in industrial progress and human development indices.

Over 76 years, the DMK has a long history, both as the ruling party and as the Opposition. The question now is: Has the DMK remained true to the founding principles Annadurai set? What path has it travelled, and how have its ideologies evolved? A re-examination becomes necessary.

To determine whether the DMK can be considered a social movement with an impact beyond elections, a crucial question needs to be answered. Does the Dravidian party embed itself so deeply in the lives of the people — so that large sections of society consider it their own?

Take the case of KP Sundaresan, an 80-year-old resident of Puzhal in Chennai.

“I joined the party in 1962, inspired by Anna. For me, being Tamil means never bowing down to anyone. Tamil identity is important, state rights are important,” he recalled when asked about his lifelong connection with the DMK.

Sundaresan, who retired as a lower-level employee of the Union government, is not wealthy. Yet, his three brothers, two sons, and even his grandsons have all been active in the DMK across generations. From Anna to MK Stalin, he has worked under every leader.

Even today, at 80, Sundaresan serves as a local unit secretary of the DMK. When asked what kept him in the party all these years, he replies: “When I think of DMK, it reminds me of state rights, autonomy, and linguistic pride. If we want to protect our rights, we need the DMK. That’s why my entire family, generation after generation, continues in this movement.”

Across Tamil Nadu, particularly in the 1950s and 1960s, this was the case with countless families. The DMK attracted a generation of young idealists — rural students who had migrated to cities in search of jobs, those who entered government service, and those who longed to break free from social oppression.

“Periyar’s Self-Respect Movement and propaganda did not operate deeply at the grassroots. Anna, from the 1940s onwards, made it his mission to carry the movement to every village by forming branch committees. Every week, in journals like Kudiyarasu and Dravida Nadu, he published reports on the number of new branches that had been opened. He was deliberate in constructing an organisational base and passionate about mass mobilisation,” said Tamil Kamarajan, a scholar, editor and researcher of Tamil intellectual history.

This was a major point of difference between Periyar and Anna. Annadurai never compromised on Periyar’s core principles of social reform. However, when it came to mass politics and elections, he had to broaden the movement’s appeal.

“That is why he introduced slogans like ‘Ondre Kulam, Oruvane Devan’ (One Clan, One God). As an atheist, he did not oppose believers, but instead argued that humanity is one and, if at all, there is only one God. Similarly, while he refused to exclude Brahmins entirely, he also ensured they did not dominate key positions within the party. His stance was: We will not ban them, but we will not allow them to control the movement either,” explained Kamarajan.

Thus, while standing firm on social reform, Annadurai simultaneously shaped the DMK into a party that could reflect the aspirations of the masses. This attracted waves of young idealists, embedding the party deeply within Tamil families and society.

When India attained independence in 1947, Periyar declared it a “day of mourning.” He argued that freedom had merely shifted power from the British to the upper-caste elite of India, and hence he wanted no part in the new system. Instead, he raised the demand for a separate Dravida Nadu.

Annadurai, however, diverged from Periyar on this point. While he supported the Dravida Nadu demand, he argued that independence was still cause for celebration, as colonial rule — one of the two great burdens, the other being caste hierarchy — had at least been lifted. From here, differences between the two leaders began to sharpen.

“As Anna saw it, the real question was: Will you stand outside a new democratic system and only exert pressure, or will you participate, seize power, and bring change from within? That was Anna’s position,” explained senior journalist AS Panneerselvan.

Even after founding the DMK in 1949, Anna did not abandon the Dravida Nadu demand, but he was pragmatic. He held on to it as the ultimate goal, while keeping the scope to reinterpret it.

Thus, in 1963, when the Indian government passed the Sixteenth Amendment (the Anti-Secession Law), Anna formally dropped the demand for a separate Dravida Nadu. Yet, he never abandoned its essence. Instead, he intensified his advocacy for federalism.

For example, in March 1965, during the parliamentary debate on the Official Language issue, he famously argued: “Real unity in India comes not from making everyone the same (uniformity), but from respecting and harmonising diversity (unity in diversity). Language alone cannot hold the country together — economic fairness, respect for regions, and cultural balance are equally necessary.”

There are numerous such speeches.

Thus, what began as the radical call for Dravida Nadu evolved into a sustained demand for federalism within the Indian Union.

“When they said Dravida Nadu, their critique was that the Indian Union was not truly federal. Their argument was: if that’s the case, we will build a genuinely federal Dravidian state. Over time, that same aspiration translated into the demand for real federalism within India,” explains Tamil Kamarajan.

However, when the Sixteenth Amendment (the Anti-Secession Law) created a legal block, Annadurai rethought his strategy.

“He believed: We can certainly fight for our policy of Dravida Nadu, but the repression that would follow and the hurdles it would create for our greater goal — delivering good governance to the people — would be enormous. That is why he moved towards federalism as an extension,” explained Kamarajan.

In this evolution, “The demand for a Dravida Nadu with true federalism became a call for an Indian Union with strong federalism and autonomy for states, encompassing all Indian states, not just the South,” he added.

Kamarajan pointed to the anti-Hindi resolution passed under Annadurai’s tenure as chief minister as an excellent example of this shift.

“The resolution demanded that the special privileges granted to Hindi be removed and that all Indian languages be given equal status. In the meantime, English could serve as a link language. So, the resolution was not just for Tamil — it was for the rights of all Indian languages.”

This extension continued with the formation of the Rajamannar Committee in 1969 by then-chief minister M Karunanidhi, set up under Justice PV Rajamannar to examine Centre–State relations. Its recommendations culminated in the 1974 State Autonomy Resolution.

Thus, Kamarajan argued, federalism and Dravida Nadu were essentially the same concept: Federalism was the extended, reinterpreted demand of the Dravida Nadu idea.

Before his death, Annadurai wrote an article in Homeland magazine that later became a reference point for Karunanidhi. At the time, Kerala’s Chief Minister EMS Namboodiripad was locked in conflicts with the Union government over state rights.

In that piece, Annadurai observed: “I have not come, like EMS, to constantly harass the Union government or to keep fighting with it. But neither do I believe that without doing anything, we can achieve everything. Why do I seek power? To show the people how fraudulent this system is. There is a huge gap between what is written on paper and what happens in practice. This is not a real federal structure. If I can make the people realise that, it is itself a major achievement.”

According to Panneerselvan, “When the Union government holds all the powers and promotes a model of holding together, it becomes a nation-state that is stronger than its people. But what the DMK and Anna argued for was coming together, where the people are more important than the state machinery. All of Anna’s speeches were essentially about how the Union should be structured within Indian nationalism.”

“The DMK clearly understood that only through power-sharing can people truly be empowered. And that power was not sought for one party or one state alone — it was for all of India, for all states in the federal system. The DMK pushed this as a movement. From demanding that chief ministers hoist the national flag on Independence Day to today’s struggles over GST revenue sharing, the essence remains the same: equal rights for all Indian states, not just Tamil Nadu,” he added.

At the national level, a long-running narrative has painted Dravidian politics as divisive — accused of supporting separatism, breaking India apart, or hating India and Hindus. Often, comparisons are drawn between Hindutva nationalism and Dravidian nationalism, equating the two. But Dravidian scholars and leaders see it differently.

“Dravidian nationalism does not exclude anyone. The Dravidar Kazhagam may have excluded Brahmins, but the DMK always proposed a nationalism that included them, only without giving them power to dominate. This distinction has been repeatedly emphasised, not just in elections but in every sphere,” said Kamarajan.

By contrast, he explained, “Hindutva politics systematically excludes Muslims. Dravidian politics, on the other hand, speaks against the dominance of an upper-caste social order. There is a difference between opposing a dominant group and excluding an entire religious community.”

He elaborated, “Hindutva builds a politics of hatred to establish Brahminical supremacy. Dravidian politics, in contrast, challenges that supremacy. Comparing the two is absurd — it is like comparing a dominant group with a marginalised one.”

Panneerselvan insisted that such debates must be based on empirical evidence. As an example, he cited the three consecutive Lok Sabha victories of Narendra Modi. “While much of India swung in one direction, Tamil Nadu remained firmly against it all three times. The BJP has been unable to gain ground here because its religious politics cannot take root. That is due to the decades of groundwork laid by the Self-Respect and Dravidian movements,” he points out.

This raises a common question: If that is the case, why has the DMK sometimes allied with the BJP?

Panneerselvan responded, “In 1998, the political climate was shaped by the Congress’s stance on federalism. The NDA’s declaration on power-sharing, followed by the Common Minimum Programme, guaranteed that Article 370 would not be touched, a Uniform Civil Code would not be imposed, and the states’ basic rights would not be curtailed. On this basis, the DMK entered an alliance, and it brought real benefits.”

“For the first time, a Dalit judge from Tamil Nadu was appointed to the Supreme Court. But notice how principled the DMK remained: Not once did it accept a Governor’s post that would violate its federal ideals. Even after three decades of influence at the Centre, not a single DMK leader has served as Governor of any state. That speaks volumes,” he added.

In Tamil Nadu’s political history, most ruling parties have focused on development as their primary goal.

For instance:

Today, Panneerselvan argued, the reason Tamil Nadu stands united against religious politics lies in the DMK’s governance shaped by the Self-Respect Movement.

Panneerselvan argued that Tamil Nadu’s resistance to sectarian politics today stems from the Self-Respect Movement’s policies implemented by the DMK.

“In the last three general elections, Tamil Nadu’s divergence from the national trend demonstrates the Dravidian movement’s achievements. Outsiders call welfare schemes ‘freebies,’ but because education was extended to all, the Gross Enrolment Ratio is high. Primary health centres in every village reduced maternal mortality. Free bus passes and fare-free travel are not mere perks — they are empowerment programs for women,” he said.

“Locally, if an 80-rupee job is available, by travelling to another town for 160 rupees, you can access a job; that mobility matters. Every scheme had long-term thinking behind it — that is why Dravidian governance has produced observable growth in Tamil Nadu,” he added.

When asked whether the AIADMK — which has ruled more days cumulatively than the DMK — also deserves equal credit for development, Panneerselvan gave the AIADMK credit in two respects.

“Under MGR, there was a competitive dynamic: If DMK brought a scheme, AIADMK tried to implement it better. For example, the mid-day meal scheme was introduced by the Justice Party’s Sir PT Thiagarayar, expanded in Karunanidhi and MGR’s times, and today, under (MK) Stalin, it has evolved into the breakfast programme,” he said.

“One thing is improving existing schemes; another is continuing them without co-opting or killing them. AIADMK did the former, which aided Tamil Nadu’s progress,” he added.

He further said that AIADMK’s tenure could be divided into three phases: The MGR era, the J Jayalalithaa era, and the post-Jayalalithaa era. “Up to about 2000 it was reasonably stable, but after 2001 competitive politics faded and that was harmful,” he says.

As examples, he cited three actions by Jayalalithaa that he considers problematic: Moves against the Anna Centenary Library, converting a newly built assembly complex into a hospital for political reasons, and delays in the Metro project.

Panneerselvan further contended that the AIADMK that came after Jayalalithaa’s death became an administration that often acceded to many central laws pushed by the BJP, citing, for instance, the electricity bill. “It became a paralysed structure,” he said.

Similarly, Kamarajan divided the DMK into two periods: The pre-neoliberal DMK and the post-1990s DMK. “Earlier, its ideals and the administrative setup were different; later they changed in ways that are visible, especially on corruption-related issues,” he noted.

He added, “Why the DMK has remained a major political party is because it represents the non-Brahmin mass across communities. It continues to articulate their aspirations; it functions as a language of power and enjoys broad support. So a leader who can adopt and speak that language is enough to head the movement.”

When it comes to the AIADMK, he says its identity was built around charismatic leaders: MGR as the benevolent hero, Jayalalithaa as the iron lady. After their deaths, Edappadi K Palaniswami has tried to project himself as a leader among the common people. But if an attractive leader opposing the DMK emerges, attention may shift.

Caste dynamics in Indian electoral politics are deep-rooted; Tamil Nadu is no exception. Critics say Dravidian parties have strengthened caste calculations in elections, and particularly the DMK is often accused of doing this. But Panneerselvan and Kamarajan both argue the issue is complicated.

“You cannot erase a built-up, 3,000-year caste structure in a hundred years,” Panneerselvan says, but the Dravidian movement prevented its spread. “After the 1960s, religious and caste riots did not engulf Tamil Nadu as a whole; they were contained locally,” he points out.

Both Periyar and Anna are recorded as having attended and addressed caste assemblies before independence. They urged those gatherings to build schools and fight for national unity while underlining that caste is a tool of oppression and that treating someone as inferior because of caste is a Brahminical mindset, Kamarajan notes.

After the 1950s, Periyar focused more on anti-caste conferences. There is little record of Anna participating in caste association conferences. Anna’s view was that Brahminism is the mindset of considering another person inferior because of caste; he did not craft a politics that excluded people on that basis. Early DMK records do not show caste calculations in its founding phase.

However, Kamarajan observed that caste calculations in electoral politics seem to have become prominent only after the 1980s. He explained that after the 1970s, two things happened following committee reports for backward communities: The DMK’s objective included classifying those groups, granting reservations and other benefits to uplift them.

At the same time, members of particular castes began to organise themselves to secure disproportionate shares of those benefits, forming caste-based political groupings. That process ended up creating a deeper caste-based political dynamic.

“There is no monolithic caste group anymore. Take, for instance, the Vanniyar category — it is not a single homogenous caste. Multiple caste subgroups were aggregated to form a large political caste bloc. Similar processes occurred among intermediate castes and in Dalit politics, too,” he said.

So, according to Kamarajan, it is difficult to conclude that votes are obtained solely on the basis of caste. Political parties find it easier to select local representatives or community leaders who can communicate with local people and act as intermediaries; this makes caste-based mobilisation a convenient tactic.

However, that does not prove that an entire caste association represents the whole community’s voice. Conversely, one cannot claim that these caste mobilisations had no impact either.

When the DMK started, Anna insisted that social reform following Periyar’s principles was paramount even as they entered electoral politics. However, whether that spirit still breathes in the party is a crucial question — and central to any re-examination.

Kamarajan argued, “They have lost the capacity to interpret what they once said for the present. Anna taught that if you think in terms of social hierarchy — seeing yourself as superior and others as inferior — that is Brahminism. As a political party that must bring all communities together, the DMK has failed to sustain the ability to craft that kind of political language today.”

He said that the party moved from seeing power as secondary to social reform as primary, to now negotiating for power itself. “A political party necessarily develops hierarchies to seize power — whether in China, Russia, or elsewhere. In a caste-structured society like India’s, a party’s internal hierarchy tends to mirror social hierarchies.”

“So yes, your practices may have faults or corrupt tendencies. But if you decide to shed all of that and return to purity, you cannot reach that place again. A party’s longevity in power is what sustains it,” Kamarajan argued.

Panneerselvan offered another view: “The party’s form has changed to suit the times.”

He believes that the success of the DMK and the Dravidian movement is precisely why sectarian forces have not made deep inroads into Tamil Nadu. “The three election results show that the people and the movement’s work over decades have delivered,” he said.

(Edited by Muhammed Fazil.)