Published Jul 27, 2025 | 9:00 AM ⚊ Updated Jul 27, 2025 | 9:00 AM

The Union Government has allocated over 1.7 lakh hectares of forest for infrastructure development.

Synopsis: Environmentalists warned against India sacrificing long-term ecological stability and public welfare for short-term economic gains. With over 1.7 lakh hectares of forest land cleared between 2014 and 2024, they felt it was a systemic failure in planning and policy prioritisation.

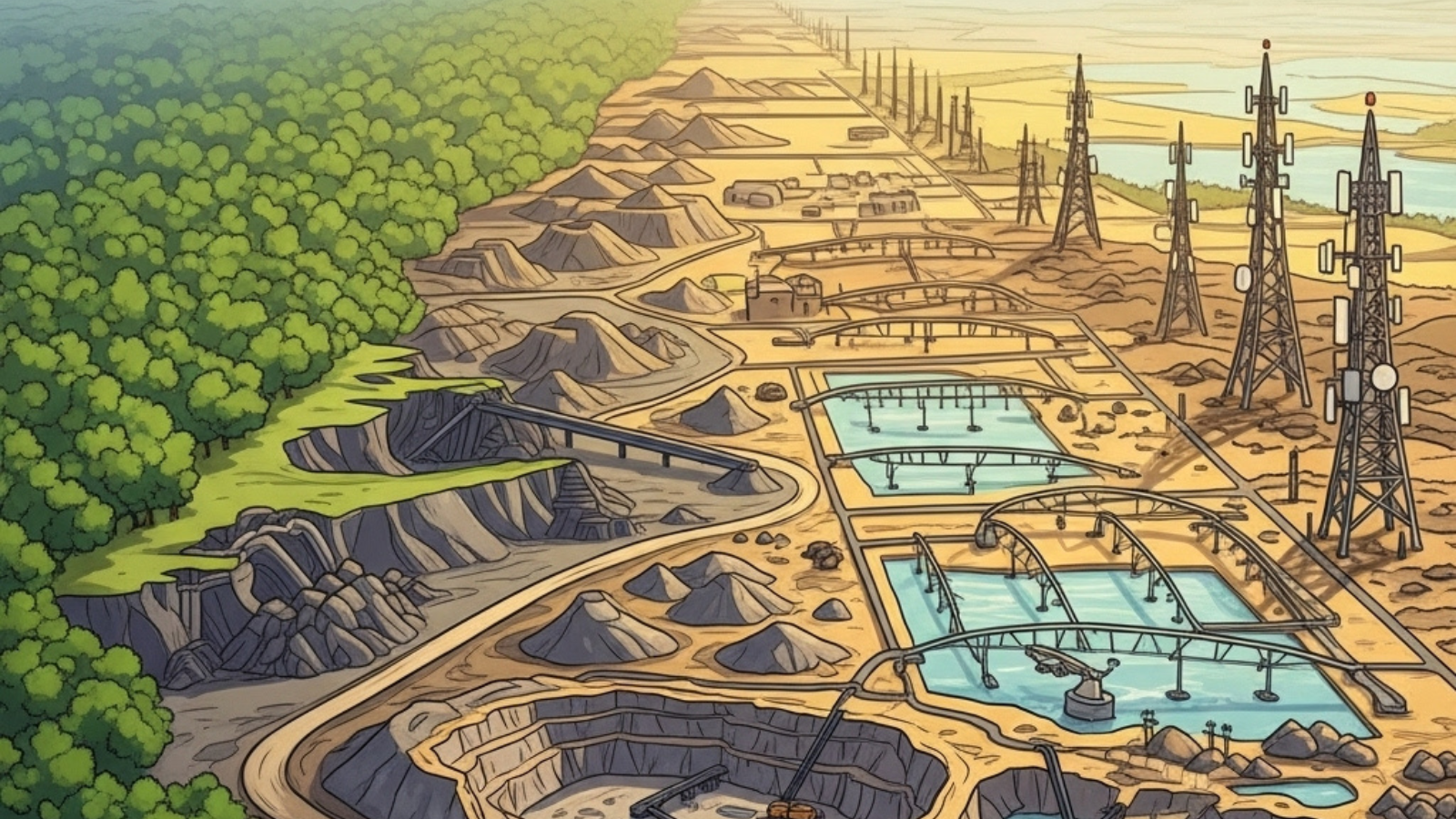

India approved the diversion of over 1.7 lakh hectares (1,739 sq km) of forest land for non-forestry purposes between 2014 and 2024, with mining and hydel projects topping the list.

The figure exceeds the combined area of Bengaluru (741 sq km), Hyderabad (650 sq km), Mysuru (128 sq km), and Mangaluru (170 sq km).

Minister of State for Kirti Vardhan Singh said 1,73,984.3 hectares of forest land were approved for various non-forestry purposes between 1 April 2014 and 31 March 2024.

The minister was replying to a question by Congress MP Sukhdeo Bhagat in the Lok Sabha on 21 July.

While the government maintained that such clearances were granted under stringent checks and under “unavoidable circumstances,” environmentalists and experts argued that the scale of diversion was unsustainable and potentially disastrous in the face of climate change.

The forest clearances have been approved under the Van (Sanrakshan Evam Samvardhan) Adhiniyam, 1980 (previously the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980), which regulates the use of forest land for non-forestry purposes.

These diversions were subject to several mitigation measures, including:

The Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change said the clearances were granted only after “scrutiny” and “adequate mitigation,” with the intent to balance ecological loss with developmental needs.

According to the detailed annexure submitted in the Lok Sabha, the largest diversions were seen in three major sectors:

Other significant diversions included land for defence projects (149 sq km), railways (80 sq km), and power transmission lines (172 sq km).

Diversion of forest land for industries.

Speaking to South First, Donthi Narasimha Reddy, an environmental activist and policy researcher, criticised the ministry’s approach to forest diversion.

“It shouldn’t have been done to begin with,” he said. “The Ministry of Environment is working as if its objective is to convert forest land into industrial land.”

Reddy pointed out that each forest played a unique ecological role based on its region and biodiversity, beyond its broader function as a carbon sink. “When a forest in one part of the country is diverted and then compensated by a plantation in another, the ecological loss is not truly addressed,” he said.

He also took issue with the government’s frequent reference to “unavoidable circumstances” in its justification.

“How can they say that? Between the environment and development, there lies the concept of sustainable development. That middle ground is completely missing,” he noted.

One of the most contested parts of the government’s forest clearance policy was the CA. While it looked like a solution on paper, Reddy argued that CA often failed in practice.

“Can they show how much they have planted in the last few years and where?” he asked. “They just do this for the sake of it. They do not care if the saplings die or if they plant something that disrupts local ecosystems.”

He further added that mature forests, which may have developed over centuries, cannot simply be replaced by monoculture plantations or saplings planted on degraded or unsuitable lands.

Another serious concern raised was the indirect ecological damage caused by these projects, which often extended beyond the approved clearance area.

“With mining and quarrying, even putting aside the tendency of this industry to illegally expand in its allocated premises, there is dust pollution, water contamination, soil degradation, and constant heavy vehicle movement — all of which ruin the surrounding forests,” Reddy explained.

This “ecological spillover” has often not been accounted for in clearance reports or environmental impact assessments (EIA), he added, making the official figures an underestimation of the real damage.

While infrastructure development was essential — especially in a growing economy like India — experts argued that its design should not come at the cost of long-term environmental health.

“People think a road through a forest might be a necessity. However, they fail to understand that a road can be highly destructive for the ecosystem — not just during construction, but forever,” said Reddy. “The material used, the noise, and the continuous movement of vehicles permanently alter wildlife behaviour and habitat.”

Moreover, large-scale irrigation projects often involved the displacement of locals. “They not only take away the land but then relocate and displace communities within forests again, further fragmenting forest cover,” he added.

“With the way things are today, one must not divert any forest lands,” Reddy stressed. “The consequences of global warming will catch up before these compensatory trees can grow.”

Dr. Lubna Sarwath, a long-time environmental activist and academic voice in India’s green movement, joined the growing list of voices raising alarm over the extensive diversion of forest land for infrastructure and industrial projects.

Echoing a broader concern among environmentalists, she warned against India sacrificing long-term ecological stability and public welfare for short-term economic gains. With over 1.7 lakh hectares of forest land cleared between 2014 and 2024—surpassing the total area of four major Indian cities combined—Dr. Sarwath felt it was a systemic failure in planning and policy prioritisation.

“The Supreme Court has said that development cannot come at the cost of ecological destruction,” she said, referencing repeated judicial observations that stress environmental sustainability as a cornerstone of public interest.

One of her key concerns was the aggressive push to exploit mineral-rich forest lands. “A lot of forest area is rich in minerals, do we start digging it all up?” she asked. For her, this signals a dangerous shift from precautionary environmental policy to extractive governance. “What are we doing when our efforts should be focused on becoming a net-zero nation?”

“You cannot do this in the name of jobs and revenue. Climatic conditions are becoming unpredictable worldwide. Rains are shutting down cities, there are increased landslides, and even Texas is flooding at unprecedented levels,” she held

In her view, any credible economic model today must be guided by sustainability and equity, not just GDP growth. She stressed the need for foundational change in designing policies and sanctioning projects.

“It is not like we are in a circular economy. We need to conduct a social and energy audit to establish key challenges and wastage,” she said. Only through such audits, she argued, can the true costs of energy-intensive, resource-guzzling industries be measured.

Dr. Sarwath also questioned the reliability and sincerity of the government’s reliance on CA—a policy that allows diversion of forest land provided replacement trees are planted elsewhere. She termed the mechanism more of a bureaucratic ritual than an effective ecological intervention.

“Compensatory Afforestation is not a novel one. It is standard and largely ineffective. How long would it take for the planted trees to become a forest?” she asked. “A tree serves a function from the base of its deepest roots to the tip of its topmost leaf. Who or what can replace that?”

She proposed an alternative: Reversal of sequencing. “If they are that eager, they should first plant the compensatory forest and then begin their respective projects,” she said

For Dr. Sarwath, environmental protection was not just an ecological or scientific issue, but deeply political and moral.

“Government policies and initiatives should be in the public interest. Health and life supersede employment and revenue,” she said, pointing to the growing burden of air pollution, water scarcity, and disease that often followed environmental degradation.

She felt that India should adopt sustainability benchmarks akin to those in Bangladesh. “In countries like Bangladesh, it is a state policy that business loans are only available once they meet certain sustainability standards. That is a non-negotiable. India should implement something similar.”

At its core, she argued, the entire framework of current land-use policy has been skewed. Instead of enabling a green future, it amounted to mortgaging it for short-lived economic wins.

“The irony is that they are setting everyone up for long-term economic losses for quick economic gains of the few in the short term,” Dr. Sarwath added.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).