Published Jan 18, 2026 | 9:00 AM ⚊ Updated Jan 26, 2026 | 8:46 AM

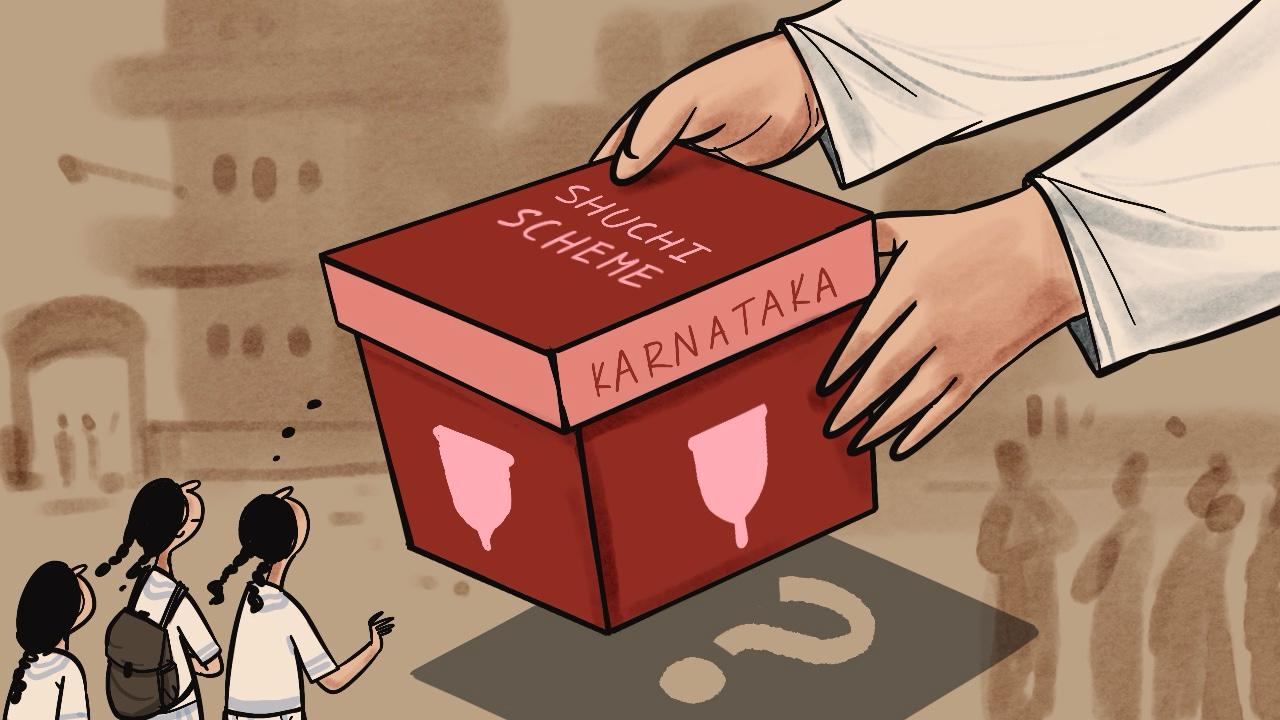

Why Karnataka's shift to menstrual cups in schools could see challenges

Synopsis: Recently, the Karnataka government announced that it would distribute menstrual cups to girls in Classes 9 to 12 under its Shuchi scheme from the next academic year. However, students and parents expressed concern over its usage due to a variety of reasons, including ease of usage, lack of proper awareness, cultural issues and others.

Bhavani, a Class 9 student in a government school in Bengaluru, has to skip classes on days when her menstrual flow is heavy. Going to school would mean having to use washrooms that are unhygienic and lack even basic facilities such as dustbins or a continuous supply of water for the safe disposal of sanitary napkins.

“I don’t know what they are,” she told South First when asked about menstrual cups. Her answer is significant since, in a one-of-its-kind move, the Karnataka government recently decided to distribute menstrual cups to girls in Classes 9 to 12 under its Shuchi scheme from the next academic year. The scheme is aimed at making menstruation more cost-effective and environmentally friendly.

According to a government order, 19,64,507 girls in Classes 6 to 12 are beneficiaries of the Shuchi Programme 2025–26. Sanitary napkins will be provided to girls in Classes 9 to 12 for the remaining three months of the year to help with the transition, and one cup each will be given to students in this age group from next academic year. Distribution of sanitary napkins will continue for students in Classes 6 to 8.

The government is procuring 10,38,912 menstrual cups through Karnataka State Medical Supplies Corporation Limited (KSMSCL).

While the move has been lauded by many, it also raises concerns about whether cultural taboos or misconceptions around internal products and bodily autonomy might make it difficult for menstrual cups to be accepted in rural or conservative communities. Additionally, questions about infrastructure also arise: The condition of washrooms in many government institutions has long been inadequate, even for the safe disposal of sanitary napkins.

“I don’t use them, so I wouldn’t want my daughter to use them either. We are much more comfortable with sanitary napkins. They don’t hurt, but I think cups would be more uncomfortable for a child like her,” said Bhavani’s mother, who works as a domestic worker in an apartment complex in the city.

The decision regarding a shift to menstrual cups was made after a pilot study conducted by the Department of Health and Family Welfare in 2022-2023 in Dakshina Kannada and Chamarajanagara districts. As part of the Shuchi – “Nanna Maithri” menstrual cup project, 15,000 beneficiaries had been identified (studying 1st year and 2nd year PUC) to promote good menstrual hygiene practices with the usage of scientific reusable menstrual cups.

However, beneficiaries selected for the pilot project had reported that no other awareness programme was conducted by the government apart from two short offline and online trainings on menstrual cups for Anganwadi staff and ASHAs by a Bengaluru-based NGO. In fact, several frontline workers who had been appointed to train students on the usage of menstrual products did not express confidence in using cups.

“Even in cities like Bengaluru, using a tampon was such a huge taboo. Even today, many women prefer to use a sanitary pad over a tampon,” Brinda Adige, a gender activist, told South First. According to the National Family Health Survey (NFHS 5) report, 69.1 percent of women aged 15-24 years use sanitary napkins, 2.9 percent use tampons and 0.3 percent menstrual cups, and 21.9 percent use locally prepared napkins in Karnataka.

Activists also pointed to structural and social barriers in rural areas. They say many girls grow up with little privacy at home, which deepens the secrecy and discomfort surrounding menstruation and menstrual products.”Many homes do not have separate rooms for children. The whole family stays in one living room, with probably one bedroom and one toilet,” Adige explained.

For Bhavani, the idea of an internal menstrual product clashes with how she has been taught to talk about her body — with hesitation and discomfort. Although the government has maintained that orientation sessions would be conducted to provide guidance on usage and disposal, activists raised concerns about whether the government was adequately prepared to address deep-rooted cultural taboos in rural areas.

Medical experts, however, explained that girls in the concerned age group can use menstrual cups if the use and disposal are demonstrated properly.

“What is important is that they are given accurate information. They should be taught how to understand and be comfortable with their own bodies,” said Dr Shaibya Saldanha, a gynaecologist and co-founder of Enfold Proactive Health Trust. She added that this is also the age at which students begin learning about the reproductive system in schools, making it an appropriate time to introduce them to the use of menstrual cups.

However, Dr Saldanha cautioned that their use may be challenging in areas where water supply is irregular and toilet facilities are inadequate. “When I advise my patients, I usually tell them to start with a tampon (before moving to a menstrual cup) to get a sense of their body. But it depends from person to person,” she said.

Dr Saldanha also urged the government to hold a meeting with parents and school management committees to prevent backlash that could affect the entire program.

When South First spoke to three government school students from Class 9 from Channapatna, all of them admitted in hushed tones that they would find the method uncomfortable. “It sounds painful. We don’t know anyone who uses it. Our mothers used to tell us that they would use cloth before they could access sanitary napkins. They don’t talk about cups,” one student said.

Another student expressed concerns about how they would empty the cup into the toilet in the school, where water is not available consistently. At least 170 government schools in Karnataka lack toilets, School Education Minister Madhu Bangarappa stated in response to a question by Member of Legislative Council (MLC) N Ravikumar in December 2025.

Additionally, a total of 701 government schools do not have a separate toilet for girls, and 2,039 government schools do not have a separate toilet for boys, which forces all students to use common toilets.

Apart from Karnataka, the neighbouring states of Tamil Nadu and Kerala have also introduced initiatives to promote the use of menstrual cups among girls and women. However, doctors from these states said that while students are introduced to the concept as early as Class 9, they are generally not advised to begin using menstrual cups until after Class 10.

“We explain what menstrual cups are, but we do not recommend their use at this stage, as proper hand and cup hygiene is critical,” said Dr Maria Varghese, a doctor based in Kerala.

According to a study conducted among medical students between the age group of 18-25 years from Sree Balaji Medical College and Hospital, Chennai, good knowledge regarding menstrual cup usage was seen in 43.6 percent of the study participants.

However, 40 percent found that menstrual cups are difficult to use. “Although awareness about menstrual cups was high among medical students in the current study, in-depth knowledge of the use and type of material used was poorly understood even within the medical community,” the study found.

Another study conducted among females of the reproductive age group (the mean age of study participants was 25.68 years) in an “urban setting” of South Kerala found that lack of knowledge and fear of insertion were the major reasons for not trying a menstrual cup. Additionally, discomfort and leakage were the most important problems reported by participants.

“This study showed that 47.4 percent was afraid of the insertion of the cup, 19.1 percent had a lack of knowledge, and nine percent avoided the use due to cultural beliefs,” the study said.

Meanwhile, for the government, the move comes as a cost-effective measure. Currently, the government spends around ₹71 crore every year to supply sanitary napkins to beneficiaries under the Shuchi scheme.

By providing six units of sanitary napkins and one menstrual cup for six months (instead of 12 units of sanitary napkins), the government estimates that it would save around ₹17.26 crore, according to a government order issued in this regard. Officials have reiterated that menstrual cups are not a replacement for sanitary napkins but an additional option.

To recall, the scheme was earlier halted in 2020 for four years due to a lack of funds. It was restarted in January 2024. However, students are still waiting for their kits for the academic year 2025-26 as the state government decided to invite tenders for the procurement process, unlike the previous year when it availed the exemption under Section 4G of the Karnataka Transparency in Public Procurements (KTPP) Act, 1999.

An official from the Health Department told South First that the primary objective of the shift is that the state wanted to be more environmentally friendly, as menstrual cups are reusable.

However, the official did mention that they do expect some resistance, as girls and women are used to sanitary napkins. The government plans to hold awareness programmes, Information Education Communication (IEC) programmes and a lot of hand-holding to ease into this shift.

Additionally, the government expects that the younger generation will be more open to experiments, unlike the older generation.

(Edited by Muhammed Fazil.)