Published Apr 12, 2025 | 9:00 AM ⚊ Updated Apr 23, 2025 | 8:44 PM

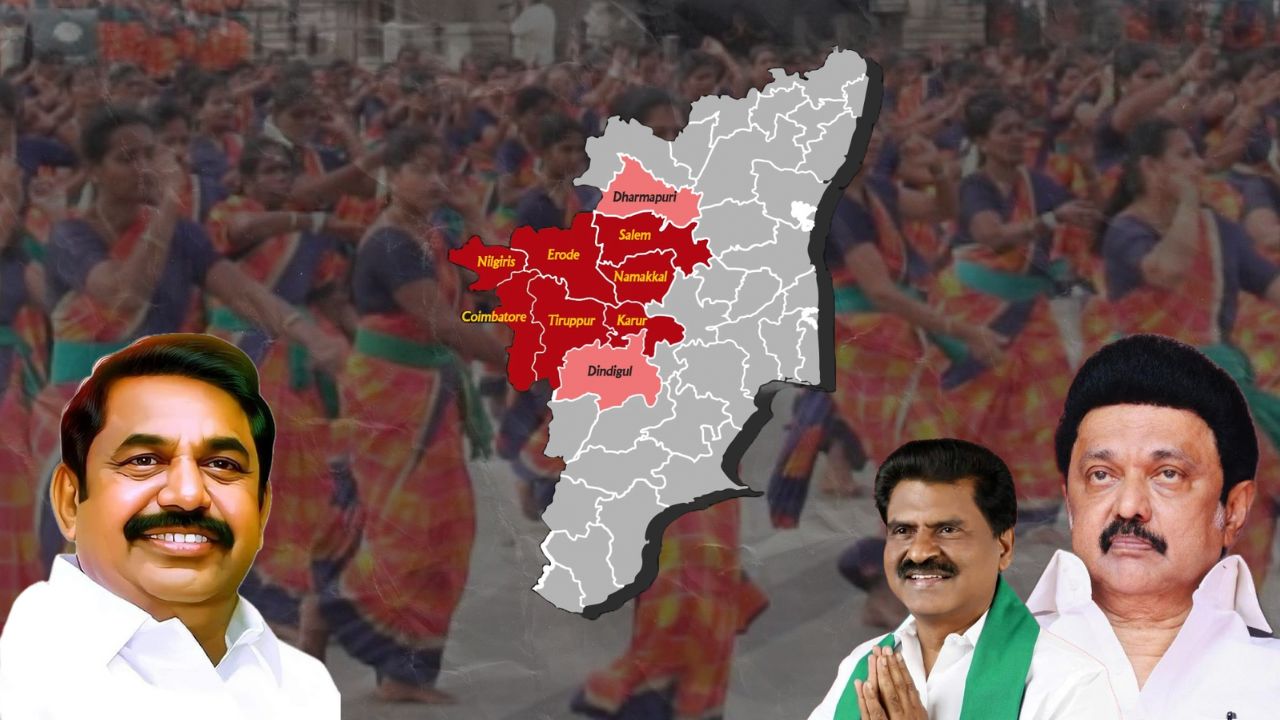

In the western districts of Tamil Nadu such as Coimbatore, Erode, Tiruppur, and Salem – the Kongu Vellalar Gounders, classified as OBC, form the majority.

Synopsis: Tamil Nadu’s ruling DMK, despite its anti-caste image, continues to partner with the KMDK, a regional ally whose leaders have made inflammatory caste-based remarks. The DMK’s support for KMDK-led cultural events, such as Valli Kummi performances, is seen as a move to win over the influential Kongu Vellalar Gounder community. Critics say the alliance highlights a growing ideological dissonance, where electoral calculus increasingly trumps the party’s professed commitment to social justice.

Ahead of the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, the Kongunadu Makkal Desiya Katchi (KMDK) was forced to replace its candidate for the Namakkal constituency.

A speech delivered by Suriya Moorthy in 2014 resurfaced and ultimately cost him his candidature. In it, he had stated, “I will abort opposed community children while they are still in their mother’s womb.”

A Kongu Vellalar Gounder, Moorthy had also made inflammatory remarks inciting violence against oppressed communities and opposing inter-caste relationships during that event.

Although he lost his candidature, he continues to serve as the party’s Youth Wing Secretary.

Six months earlier, on 13 November 2023, the party found itself at the centre of another controversy – this time at a Valli Kummi cultural event in Erode.

KKC Balu, the Treasurer of the KMDK, who also leads a group named Kongu Nadu Kalaikuzhu (Kongu Nadu Arts Troupe) training women in the traditional folk dance Valli Kummi in the Erode region, made women participants pledge to marry only Gounder men. The event sparked widespread outrage.

On its own, the party’s stance on caste is quite apparent. But viewed within the larger political landscape, the situation becomes curious – if not bewildering.

The KMDK is an ally of the ruling Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), a party that positions itself as anti-caste and advocates an egalitarian Dravidian model of governance.

Yet, in the 2021 Assembly elections, the DMK allotted a seat to the KMDK, and the party president, ER Easwaran, was elected as an MLA from the Tiruchengode constituency.

In the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, the party’s candidate Matheswaran, who replaced Suriya Moorthy, won from the Namakkal parliamentary constituency.

More recently, DMK supremo and Tamil Nadu Chief Minister MK Stalin attended a Valli Kummi performance organised at the Codissia grounds in Coimbatore, where 10,000 female artists participated.

The event was organised by the same Kongu Nadu Kalai Kuzhu and the KMDK.

So why does a DMK Chief Minister patronise cultural events organised by a minor party whose leaders have openly incited caste-based violence and expressed discriminatory sentiments against oppressed communities?

To understand the factors at play, it is important to first understand the political clout that KMDK holds in the state and, more importantly, how it is using culture – in this case Valli Kummi – as a tool to augment that clout.

Valli Kummi is a celebrated dance form performed mainly by women. It serves as a form of communal storytelling, honouring Valli, the tribal consort of the Hindu deity Murugan.

“In the last five or six years, Valli Kummi has become seen as an exclusive cultural marker of the Kongu Vellalars,” Professor A Ramasamy, a Tamil scholar and former professor at Manonmaniam Sundaranar University in Tirunelveli tells South First.

He stresses that Tamil Nadu’s folk arts have historically not been confined by caste boundaries.

“In general, no folk art form in Tamil Nadu has historically been confined to any particular caste,” he explains.

“They have always been associated with a particular deity or a region. People of all castes living in that region would participate in those folk art forms. For instance, in North Tamil Nadu, forms like ‘TheruKoothu (street play)’ and ‘Kattai Koothu’ are performed by people across communities.”

While folk arts are often symbols of regional identities, Professor Ramasamy says certain traditions are linked to specific clan deities, especially in southern Tamil Nadu.

He cites Devarattam, traditionally performed by the Kambala Naicker community, as an example.

Yet Valli Kummi, according to Professor Ramasamy, was never exclusive to any one caste.

“Valli Kummi does not belong to any specific community. It is a devotional dance performed in worship of Lord Murugan,” he says, pointing to the widespread reverence for Murugan across Tamil communities.

He adds that although Valli Kummi is closely tied to the Kongu region and particularly to the Palani Murugan temple, it is not a universal feature at all Murugan shrines – such as Marudhamalai in Coimbatore, where it is not commonly performed.

Over time, however, the dance has taken on caste associations. Professor Ramasamy explains that while it was once performed by different communities, in the Kongu region, it came to be linked with the Kongu Vellalar Gounders.

“This is a common pattern – when a community holds demographic and land dominance in a region, they often claim cultural symbols as their own identity markers. Based on this, the dominant communities of the Kongu region appropriated Valli Kummi as part of their identity,” he explains.

“Consequently, political forces are now attempting to consolidate the votes of that community through the promotion of such cultural events.”

Vinisha, a resident of Erode, describes how this process plays out, beginning with temples.

“Initially, Valli Kummi is taught in temples focusing on art and women’s health. However, as the events progress,” she says, “they gradually turn into politically motivated gatherings.”

In each region, the dance is typically taught in temples – either community-specific or public – by a teacher or elder.

The initial focus is on devotion and well-being, with songs praising Lord Murugan and movements promoted as a form of physical exercise.

Those interested can progress to public performances, often beginning at the temple where they first learned the dance. Eventually, dancers may be invited to perform at events organised by social movements or political parties.

Vinisha observed that caste alignment can influence participation.

She notes that while both women and men are taught the dance, caste plays a different role in each case.

“Men are often directly tied to caste-based structures, whereas women are introduced to the artform through temple systems – and then gradually excluded from broader cultural and political narratives,” she says.

Caste has long played a central role in Tamil Nadu’s political dynamics, with dominant communities in each region often exerting significant influence over local power structures.

In the Kongu region – encompassing western districts such as Coimbatore, Erode, Tiruppur, and Salem – the Kongu Vellalar Gounders, classified under the Other Backward Classes category, form the majority.

This demographic reality has made the region a focal point for political mobilisation.

Professor Ramasamy notes that parties across the spectrum have sought to consolidate support from the Kongu Vellalar community through cultural symbols and figures.

“Specifically, there is a teacher in that region ‘Guru’ M Badrappan, who trains and promotes the Valli Kummi art form. By awarding him a Padma Shri award, the Union government aimed to woo his community’s support,” he says.

He adds that this form of symbolic recognition is not limited to the central government.

Similar strategies, he explains, have been adopted by state-level leaders. During his time in office, former Chief Minister Edappadi K Palaniswami positioned himself as a representative of the Kongu Vellalars.

In the current administration, leaders from the same community within the DMK have sought to affirm their standing by retaining the KMDK within their alliance.

“These symbolic moves,” Ramasamy says, “are essentially ways for each party to present itself as the political choice of a particular caste group.”

This form of mobilisation is not unique to the Kongu region. Ramasamy notes a broader pattern across Tamil Nadu, where cultural commemorations have become intertwined with political messaging.

He cites the example of Pasumpon Muthuramalinga Thevar, a revered leader of the Thevar community. Initially, memorial visits to his birthplace were largely confined to members of that community.

Over time, however, political figures, including chief ministers, began attending these events – often at the invitation of community leaders – to signal support and affiliation.

While such appearances are typically framed as ceremonial or respectful gestures, Ramasamy argues they serve a political function: projecting influence and solidarity with specific caste groups.

“Ideally, parties that claim to stand for secularism should avoid such caste-based mobilisations,” he says.

“But here, that line is blurred – politicians openly convert these cultural commemorations into political gatherings under the guise of being ‘invited.’”

Political commentator TN Raghu says the DMK is desperate to gain a foothold within the Kongu region, particularly ahead of the 2026 Assembly elections.

He points to the 2021 state elections, where the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) retained strength in the Kongu region despite the absence of former Chief Minister J Jayalalithaa, who was once the source of the party’s power and appeal.

“That is why the DMK is now desperate to gain a foothold there,” he says.

“They have brought in Senthil Balaji, given him a ministerial post, and appointed him as in-charge of the Coimbatore constituency – because Coimbatore is crucial in terms of electoral impact. DMK believes Senthil Balaji’s caste background, his resources, and his ability to win elections will work in their favour.”

But Raghu was less than impressed by the DMK’s strategy. He believes that no political party should associate itself with caste-based activities and the DMK – which positions itself as a champion of social justice – must be held to that standard.

Such involvement, he argues, contradicts the party’s stated commitment to Periyar’s ideology.

“If everything is fair in electoral politics, why even talk about Periyar? Why claim to stand for social justice?” he asks. “Can the DMK simply dismiss these caste-linked events as mere cultural programmes?”

He accuses the party of using electoral strategy to justify what he sees as ideological inconsistency. “For them, the only thing that matters is clinging to power – whatever it takes,” Raghu says.

Similarly, Raghu believes that when it comes to caste over electoral politics, both the AIADMK and the DMK, the two chief political parties in the state, are more or less the same.

“Both parties have prioritised vote banks over principles,” Raghu says, arguing that neither has taken a firm stand against caste atrocities, instead choosing a calculated silence on caste-based violence and discrimination in Tamil Nadu.

“Whether in power or not, DMK has never really raised its voice against the dominant castes. Take for instance the honour killing of Sankar and the struggles of Kausalya – DMK never staged major protests or spearheaded movements around such incidents,” he says.

“They fear that aggressively opposing caste oppression will alienate majority caste voters.

Often this silence is justified as political strategy. “But the reality is, they do not even address these issues vocally. They are far more concerned about votes. If that is the case, how can they still claim to be the heirs of Periyar’s legacy?” he questions.

Through its silence, the DMK might not be supporting caste hierarchies, but it ends up enabling caste-based violence, he asserts.

“If you truly stand for social justice, you must oppose caste oppression and speak against it – at least issue a strong condemnation,” he adds. “If you stay silent, it essentially means you are siding with caste-based violence.”

Citing a recent example, he recalls the parole release of Yuvaraj, a life-term convict linked to caste violence, who received a grand welcome.

“Did the DMK or its ministers say a single word condemning it?” he asks. “Their silence itself becomes a weapon for caste supremacists.”

Raghu is equally critical of the AIADMK, which he says has also “never been vocal about social justice or caste atrocities.”

He notes that the DMK believes AIADMK’s silence helped it gain votes in the Kongu region – a pattern he sees repeated across elections.

“In elections, it is almost like a competition between DMK and AIADMK – who can stay more silent about caste issues and thereby win more votes from caste-dominant Hindu communities,” he observes.

In regions with deep-rooted caste consciousness, both parties, he says, actively avoid doing or saying anything that might disrupt the status quo.

Unlike Raghu, Professor Ramasamy believes the DMK is going a step further than strategic silence. He suggests the party is quietly adopting elements of Hindutva politics.

“While claiming to oppose the growing Hindutva consolidation across the country, DMK too is slowly absorbing certain elements of it. On the surface, it may seem like they are resisting Hindutva politics, but if you look closer, they are also internalising some of its components,” he warns.

He traces this trend back to the party’s origins in populism.

“Right from Annadurai’s time, DMK has practised a populist style of politics. In populism, anything that helps politically is adopted. You will not find them going to these regions and speaking openly about Periyar’s anti-caste, anti-Brahmin, or atheist ideologies,” he explains.

“That is why, when DMK was founded, Anna’s slogan was ‘Ondre Kulam, Oruvan Devan’ (One community, One God) – to create a broad coalition cutting across castes. It is not unique to Tamil Nadu; everywhere in the world where populism thrives, it absorbs local cultural and religious elements. But this inevitably leads to ideological contradictions later on,” he says.

And with the all-important 2026 elections looming, Ramasamy says the real question is not just who will win the Kongu belt: “The bigger question is: who will truly speak for the minorities and the oppressed in this region?”

(Edited by Dese Gowda)