Published Jul 15, 2025 | 9:00 AM ⚊ Updated Jul 15, 2025 | 9:00 AM

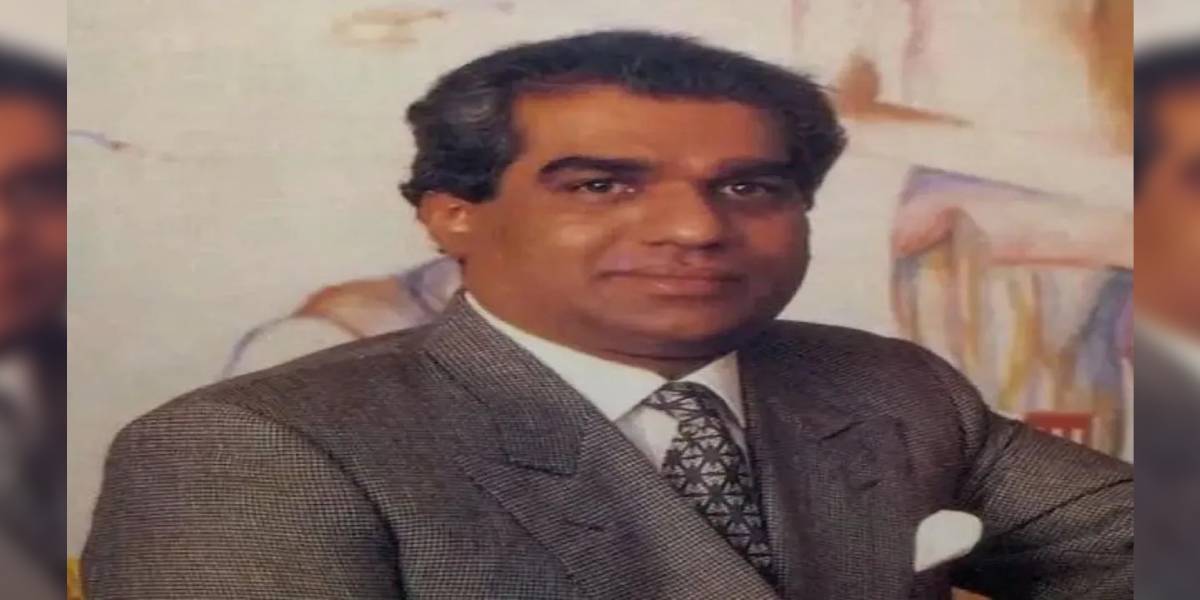

Rajan Janardhanan Mohandas Pillai, popularly known as Rajan Pillai, was born as the eldest son of a cashew exporter in Kollam, Kerala.

Synopsis: Rajan Pillai’s meteoric rise in the corporate world saw him become the chairman of the Britannia group of companies, with operations across India and the Far East. His fortunes took a dramatic turn when a business associate lodged a complaint against him with the Singapore authorities, triggering criminal proceedings on charges of fraud.

Three decades after his dramatic fall and contentious death, the ghost of Rajan Pillai is set to return to the spotlight.

The flamboyant businessman — once known as Asia’s ‘Biscuit Baron’ or ‘Biscuit King’ with a multi-million dollar empire spread across six countries — died in judicial custody at New Delhi’s Deen Dayal Upadhyay Hospital on 7 July 1995, under circumstances that continue to raise uncomfortable questions.

He was 48 years old when he breathed his last at the hospital.

Now, acclaimed filmmaker Sanjeev Sivan is working on a feature-length documentary on Pillai’s turbulent life and tragic end.

And if Sivan’s words are any indication, the film is poised to ruffle feathers.

“There will be many who’ll have to cover their faces once this documentary is out,” he says — hinting at revelations that could reopen old wounds and expose long-buried secrets surrounding one of India’s most sensational business scandals and ill-treatment in prison.

Rajan Janardhanan Mohandas Pillai, popularly known as Rajan Pillai, was born as the eldest son of a cashew exporter in Kollam, Kerala.

An engineering graduate from TKM College, Kollam, he always dreamed of becoming an international businessman.

After an early investment in a five-star hotel project in Goa, he moved to Singapore in the mid-1970s and launched 20th Century Foods, a venture that packaged potato chips and peanuts.

Though the business struggled, Pillai impressed US businessman Ross Johnson of Standard Brands, who acquired the company and brought Pillai into his inner circle.

Recognised for his deal-making flair, Pillai was sent to London in 1984 to lead Nabisco Commodities and later took charge of Nabisco’s Asian subsidiaries.

He forged partnerships with companies like France’s BSN and, by 1989, controlled six Asian firms valued at over $400 million.

However, by 1993, cracks appeared in his empire, as creditors uncovered that it was propped up by mounting debt.

Though his business empire spanned six countries, it was primarily anchored in Singapore, where he lived in a sprawling mansion on Ridout Road, complete with a swimming pool, tennis court, and a five-acre garden.

Pillai’s meteoric rise in the corporate world saw him become the chairman of the Britannia group of companies, with operations across India and the Far East. His fortunes took a dramatic turn when a business associate lodged a complaint against him with the Singapore authorities, triggering criminal proceedings on charges of fraud.

In a controversial trial — where the complainant was not made available for cross-examination — Pillai was convicted on multiple counts on 10 April 1995.

And as a court prepared to pronounce a 14-year prison term on him for defrauding the country of $17.2 million, he fled Singapore to Bombay (now Mumbai) aboard a Singapore Airlines flight.

Singapore swiftly issued non-bailable arrest warrants, alerted Interpol in New Delhi, and formally sought his extradition. Yet, Pillai managed to evade authorities.

On 28 April, he resurfaced unexpectedly in Kerala, appearing before the Additional Chief Judicial Magistrate in Thiruvananthapuram, where he was surprisingly granted bail. The Kerala High Court intervened suo motu, reviewed the case, and cancelled his bail on 26 June.

Despite mounting pressure, the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) failed to locate him. A fresh non-bailable warrant was issued on 1 July by designated magistrate MC Mehta.

Finally, in the early hours of 4 July 1995, Pillai was arrested from room 1086 of the Le Meridien Hotel in New Delhi, where he had checked in under an alias.

It’s alleged that authorities recovered medicines and alcohol from his room, though these details curiously didn’t appear in official records.

Produced in court the next morning, he was remanded in judicial custody and lodged in Tihar Jail’s cell No. 4 — marking the tragic beginning of his final days.

Arrested on an extradition request from Singapore, Pillai was produced before Magistrate Mehta, where his lawyers presented a medical certificate from Apollo Hospital warning of his critical condition due to alcohol-related liver cirrhosis.

The note highlighted alarming symptoms like vomiting and passing blood, advising urgent transfer to Escorts Hospital for a life-saving procedure.

However, while Judge Mehta, then Metropolitan Magistrate-cum-Commercial Civil Judge, Delhi, rejected the plea for hospitalisation, he instructed Tihar Jail’s Resident Medical Officer (RMO) to assess Pillai’s condition urgently — a directive that never reached its destination in time, as it was sent casually via courier.

Once admitted to Tihar, it’s alleged that the jail doctor failed to record Pillai’s medical history, and a proper assessment was never made.

Throughout the night, a day before his death, fellow inmates recalled how Pillai appeared restless, visibly unwell, with swelling and fever, yet no medical intervention came.

In the morning, his condition worsened, but instead of rushing him to a capable hospital, authorities administered a sedative injection typically used for anxious prisoners.

Only after his lawyer Pradeep Dewan’s insistence was Pillai sent to Deen Dayal Upadhyay Hospital — ironically, a facility previously acknowledged in court as unfit for treating his condition.

By then, crucial hours had been lost. Pillai was declared dead, with a post-mortem examination confirming death by asphyxia from bleeding esophageal varices, a complication of advanced cirrhosis — a death many believe could have been prevented.

It’s alleged that Pillai died in tragic circumstances, following a series of administrative lapses and medical negligence.

Sunil Gupta, a former Tihar jailer, in his searing memoir ‘Black Warrant: Confessions of a Tihar Jailer‘ recalls how a critically-ill Pillai was denied timely medical attention despite clear warnings that Deen Dayal Upadhyay Hospital was ill-equipped to treat his advanced liver cirrhosis.

An absence of an ambulance, no armed escort, and sheer administrative indifference delayed his transfer by two crucial hours. By the time Pillai was wheeled into the hospital, bleeding from the mouth, it was too late.

At the same time, to ascertain the relevant facts and circumstances leading to the death of Pillai, the Lieutenant Governor of the National Capital Territory of Delhi appointed a Commission of Inquiry consisting of Justice Leila Seth, a former Chief Justice of the Himachal Pradesh High Court, by a notification dated 27 July 1995. The report of the Leila Seth Commission of Inquiry, dated 25 February 1997 dealt with the question whether in the death of Pillai, there was negligence on the part of any authority.

In her book, On Balance An Autobiography, Leila Seth noted how Pillai’s death had, for once, shaken the “sluggish lethargy” of the system. Her report exposed severe overcrowding, poor sanitation, and woefully inadequate medical care — just six doctors for over 9,000 inmates.

Seth hoped her recommendations wouldn’t join the dust-covered files of ignored reforms.

Three decades after his tragic and controversial death, Pillai is back in public discussion, thanks to a social media post by filmmaker Sanjeev Sivan.

Marking the 30th anniversary of Pillai’s passing, Sivan announced plans for a feature-length documentary that promises to uncover untold truths about the business icon’s life and downfall.

In his post, Sivan recalled Pillai as the first corporate superstar from Kerala, whose rise from a cashew exporter to the helm of Britannia inspired an entire generation.

“He was a visionary and honest businessman, betrayed by those closest to him. His story is loaded with misplaced trust, deceit, and unexpected betrayals,” Sivan wrote.

The filmmaker revealed that he, along with his wife Deepti and writer Anirban Bhattacharya, has been researching Pillai’s story, securing exclusive access to his wife Nina Pillai and sons. The project also involves Oscar-winning screenwriter Zach Sklar.

Sivan hinted at “shocking revelations” emerging from their research and promised a theatrical release of the documentary before it heads to streaming platforms — aiming to finally tell the real story behind one of India’s most intriguing corporate tragedies.

Pillai’s story isn’t just a tale of dizzying success and catastrophic downfall — it’s a mirror to a system that failed him, and perhaps still fails many. Three decades later, his ghost is back, and this time, it might finally have its say.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).