Published Dec 06, 2025 | 9:30 AM ⚊ Updated Dec 06, 2025 | 9:30 AM

In a land dominated by a political duopoly, new experiments are targeting Bahujan communities, aiming to reshape cultural and political narratives at the margins. Pictured, a woman from the Paniya tribal community in Kerala.

Synopsis: Even in a land dominated by a political duopoly, new experiments are targeting Bahujan communities, aiming to reshape cultural and political narratives at the margins. It’s a quiet shift today, but portends significant consequences for Kerala’s future.

Union Cabinet Minister Jitan Ram Manjhi’s Hindustani Awam Morcha (HAM) quietly announced its entry into Kerala, after winning five seats in the recent Bihar Assembly elections.

The party’s leadership—National Organising Secretary Subish Vasudev and Publicity Chief Baiju Thomas said talks are underway with minor Kerala outfits and that billboards will soon appear across the state.

At first glance, HAM’s move may seem insignificant — a small Bihar-based BJP ally appearing to have little electoral space in Kerala.

But this trend signals a deeper, largely unnoticed political vacuum in the state—one that national saffron forces have been steadily trying to exploit.

Even in a land dominated by a political duopoly, new experiments are targeting Bahujan communities, aiming to reshape cultural and political narratives at the margins. It’s a quiet shift today, but portends significant consequences for Kerala’s future.

When South First contacted Vasudev, he revealed that the HAM would hold a state-level meeting in Kerala on 16 December. Leaders from various parties, including a few sitting MLAs, were expected to join the organisation.

Subish Vasudev with Jitan Ram Manjhi

He added that discussions with certain legislators have already taken place, and the initial response has been encouraging.

Vasudev pointed to a political gap that HAM hopes to fill in. He argued that minorities, Dalits and tribal communities have generally been keeping a distance from the BJP, largely because the party’s opponents projected it as one driven by the Hindutva ideology.

”Many admire Modi, but hesitate to join the BJP. HAM can function as an entry point, a new platform through which we can reach people. Kerala has space for new political formations” he said.

Santosh Kumar Suman, Bihar minister and son of Jitan Ram Manjhi, would also attend the 16 December event.

Amidst this development, a quieter political shift unfolded in Idukki.

Former CPI(M) MLA S Rajendran has been actively campaigning for BJP candidates in plantation regions like Edamalakkudy and Devikulam.

Rajendran, who had spent 15 years in the CPI(M) and been estranged from the party for nearly four years, told South First that he was only helping locals who had once supported him. He asserted that he was ”not part of any party now.”

He was suspended for a year for allegedly trying to sabotage LDF candidate A Rajas’ winning prospect in the previous Assembly election. The CPI(M) refused to reinstate him after the suspension period.

With speculation mounting, Rajendran has been rumoured to be preparing to join the BJP and may contest the next Assembly polls under its banner.

Speaking to South First, Dr Varghese George, the Kerala state general secretary of the RJD, highlighted the continuing political vacuum among Bahujan communities in the state.

CK Janu.

The decline of the BSP’s organisational presence has left a space that no party could meaningfully occupy, he said.

”Earlier, the BSP had a visible presence in local body/Assembly elections. Winning wasn’t the point; the participation itself mattered. That space remains open today” he said.

He added that this vacuum was felt most sharply within the Harijan community.

Any discussion on this absence of political representation would be incomplete without acknowledging how mainstream politics had treated CK Janu over the years.

Janu, one of Kerala’s most prominent tribal leaders and the face of the Muthanga agitation, had in August announced that her party, the Janadhipathya Rashtriya Party (JRP), was withdrawing from the BJP-led NDA.

The decision, made at a JRP state committee meeting in Kozhikode, marked another shift in her long and turbulent political journey.

Janu, known for leading Adivasi land rights struggles such as the Kudil Ketti Samaram and the 2003 Muthanga protest, had moved from activism into politics by forming the JRP and intermittently aligning with the NDA.

She stated that the JRP had consistently been sidelined within the NDA and received no real support, despite her being publicly identified with the BJP. The party’s decision was reportedly made without informing Kerala BJP leaders.

Janu had also clarified that she would not join either the UDF or LDF, and that the JRP would contest the upcoming local body elections alone.

Her association with the NDA had been on and off since 2016: joining, quitting, returning, and once again walking out, highlighting the persistent friction between her party and mainstream political fronts.

Both Dalits and Adivasis together constitute less than 15% of Kerala’s population, according to the 2011 Census.

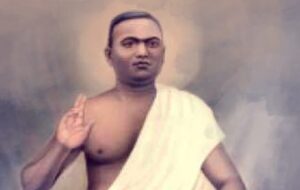

Poykayil Appachan.

In contrast, Muslims constitute nearly 27%, and as Dr TS Syam Kumar, a prominent Dalit activist, pointed out, the community in Kerala enjoys a far better socio-political, economic, and even spiritual standing compared to other marginalised groups.

”At the national level, Muslims are also a struggling community. But in Kerala, they have power and visibility” he told South First.

Ezhavas (OBC) also enjoy significant power, from political representation to cultural presence, thanks to the transformative guidance of Sree Narayana Guru, whose reforms fundamentally empowered the community.

Dalits and Adivasis, however, remain powerless on every front.

They lack political presence, economic capital, and even an independent spiritual identity. Traditional religious practices like the Theyyam of Malabar, which once stood outside Brahmanical structures, have now been absorbed into mainstream temple culture.

Except for a section of Dalits who follow Poykayil Appachan, founder of the Prathyaksha Raksha Daiva Sabha (PRDS), most oppressed groups do not have a spiritual centre that anchors dignity or collective unity.

Research students, who spoke to South First, echoed this reality: ”There is no power, no money, not even a spiritual identity for the oppressed in Kerala. This vacuum is precisely what Hindutva forces are stepping into, offering leadership posts, symbolic visibility, and even money. But these alliances will eventually collapse, because the extremes of Hindutva ideology and the lived reality of Dalit–Adivasi communities can never align. The result will be disaster, the oppressed will become even weaker.”

Rajith Kasaragod, Kerala state president of Backward and Minority Communities Employees Federation (BAMCEF), an organisation founded by Kanshi Ram for the upliftment of SC, ST, OBC, and converted minorities, said the primary crisis has been the absence of proper caste-based data in India.

Mayawati and Kanshi Ram

”There is either a lack of data or an intentional refusal to bring it to the mainstream. Without data, how do we even begin a conversation on upliftment?” ‘ he told South First.

Rajith argued that saffron politics has been tapping into the political vacuum among Dalits, Adivasis, and other Bahujan groups. This vacuum, he warned, would lead to a ”complete invasion”, if ignored.

He felt the upliftment of the Bahujan in Kerala required multilevel work — social, political, economic, spiritual, and cultural, without which the marginalised would remain vulnerable to ideological manipulation.

Opponents of a caste census claimed that it might reinforce caste divisions or lead to political misuse. But Rajith countered, invoking Kanshi Ram, who meticulously documented caste groups decades ago.

”If we don’t even know who we are, how can we demand justice? How can we measure progress?”

He stressed that without data, there would be only darkness where extremist ideologies thrive.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).