Published Jan 12, 2026 | 8:00 AM ⚊ Updated Jan 12, 2026 | 8:00 AM

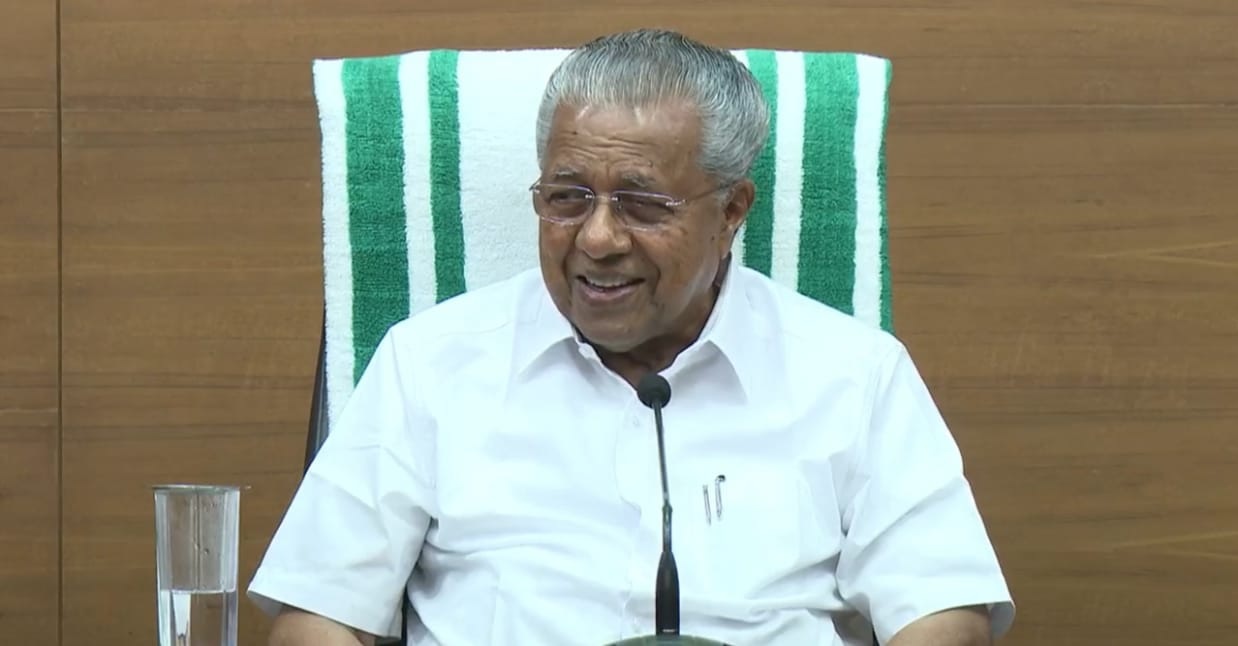

Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan said the government had already completed action on 220 recommendations.

Synopsis: The Kerala government has sparked controversy by claiming it has acted on hundreds of recommendations from the unpublished Justice (Retd) JB Koshy Commission report on the social, educational and economic conditions of minority Christians. Church bodies and opposition parties say the claim defies logic and argue that the government’s sudden urgency appears politically motivated, with the 2026 Assembly elections approaching.

With just months to go before the crucial Assembly elections in Kerala, a long-pending, government-commissioned report on the educational, economic and social conditions of Christians in the state has unexpectedly become the centre of a peculiar political controversy.

Despite being seen as socially advanced, Christian minorities in Kerala have wide internal inequalities. In 2020, Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan appointed the Justice (Retd) JB Koshy Commission to study the educational and economic backwardness and welfare needs of the community, and to submit actionable recommendations.

The Commission submitted its report to the government in May 2023. For well over two years thereafter, the state dragged its feet in acting on the findings. Neither did it release the report to the public.

That changed abruptly in the first week of January 2026.

Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan unexpectedly announced that the government had already acted on more than 220 of the report’s recommendations across 17 departments.

The claim, however, left many puzzled. Christian Church bodies and opposition parties pointed out that neither the report itself nor any item-wise account of actions taken has been placed in the public domain.

What’s more, several of the Commission’s key proposals, including changes to reservation policy, demands related to Scheduled Caste benefits for Dalit Christians, recruitment measures and educational interventions, would require legislative amendments, Cabinet approvals and other formal processes. None of these could plausibly have occurred without public disclosure.

Notably, a petition seeking the release of the full report is pending before the Kerala High Court.

The Koshy Commission examined issues affecting different sections of the Christian community, including Latin Catholics, converted Christians, Dalit Christians, and Christians living in geographically disadvantaged regions such as coastal belts, Kuttanad and hilly areas.

It received around 4.87 lakh representations from churches and organisations.

The report contained 284 main recommendations and 45 sub-recommendations and, according to the government’s own records, over 2,000 actionable suggestions spread across nearly 35 departments. It was formally transferred from the Home Department to the Minority Welfare Department in June 2023 for implementation.

Among the most significant and politically sensitive proposals were:

In October 2025, at a one-day seminar in Fort Kochi, Minority Welfare and Development Minister V Abdurahiman, while explaining a draft policy document prepared under Vision 2031, said implementation of the Justice JB Koshy Commission report would lead to major improvements in the social, educational and economic status of the Christian community. At the same time, he said unemployment levels among minority groups remained high.

Citing findings from a 2025 survey, Abdurahiman said unemployment stood at 18.2 percent among Muslims, 17.5 percent among Scheduled Tribes, 16.9 percent among Scheduled Castes, 15 percent among Upward Christians, and 14.1 percent among Backward Christians.

By comparison, unemployment among Backward Hindus was 13.6 percent, and among Upward Hindus 11.7 percent.

“These figures clearly show that minority communities in Kerala continue to face serious employment challenges,” the draft policy document states.

The document also says that of the 254 recommendations in the Justice JB Koshy Commission report, 186 have already been implemented by various departments, while 12 are under Cabinet consideration.

Steps are being taken to implement the remaining recommendations, the minister said.

After nearly two years of delay and procedural explanations, Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan convened a high-level review meeting on 6 January to assess progress in implementing the report’s recommendations.

This was followed by a press conference on 8 January, at which he said the government had already completed action on 220 recommendations and sub-recommendations across 17 departments.

The Chief Minister said departments had acted on recommendations that could be implemented under existing laws and regulations, while seven proposals were being prepared for Cabinet consideration. He said the remaining recommendations required amendments to central or state laws, compliance with court orders, or coordination among multiple departments, which had slowed the process.

Mr Vijayan announced a further meeting of concerned stakeholders on 6 February at the Secretariat to “clear confusion” and take decisions on pending matters.

He said there was no reason for apprehension and that the government had taken “all possible steps” to ensure speedy implementation. He cited meetings of department secretaries, reviews chaired by the Minority Welfare Minister, and consultations led by the Chief Secretary. The government also said a special committee headed by the Chief Secretary had been meeting regularly to examine the recommendations and coordinate action across departments.

In contrast to the Chief Minister’s January emphasis on urgency, as late as February 2025, Minority Welfare Minister V Abdurahiman told the Assembly that the recommendations were still under examination and compilation, and that a final version had yet to be submitted to the Cabinet.

Similar replies were given in October 2024 and in earlier Assembly sessions, where the process was consistently described as being at the stage of review and coordination, not implementation.

The gap between these earlier official statements and the government’s January 2026 claim of large-scale implementation has since become a major point of criticism.

Fr Thomas Tharayil, Deputy Secretary General and spokesperson of the Kerala Catholic Bishops’ Council, questioned the government’s claim, asking how as many as 220 recommendations could have been implemented across multiple departments, laws and institutions without any visible outcomes on the ground, or even basic disclosure of what those recommendations contain.

Other Church leaders point out that for more than two years after the report was submitted, the government avoided publishing it, despite repeated and “reasonable” demands.

They also say that even when Christian representatives were invited for discussions in recent months, the meetings lacked substance, as participants were not told which recommendations had been accepted, rejected, or claimed to have been implemented.

In the past, editorials in community newspapers and statements from Church leaders have recalled unresolved disputes, including the long delay in regularising around 16,000 teachers in Christian managements despite favourable court verdicts, and government actions on issues such as school uniforms that were later checked by judicial intervention.

The Catholic Church’s official mouthpiece, Deepika, took an unusually sharp line, accusing the Chief Minister of portraying Christians as gullible by claiming that most recommendations had been implemented “silently”. It asked whether any other commission report in Kerala’s history had been kept from public view while being declared almost fully implemented.

The editorial questioned whether the secrecy was due to fear of public debate, concern over political fallout, or the absence of real implementation.

Church bodies have repeatedly said they are not seeking unconstitutional privileges or “backdoor benefits”. Their demand, they say, is limited to transparency, accountability and informed dialogue.

Until the full report is published and item-wise action-taken reports are made public, they warn, the government’s claims will continue to be seen as election-time rhetoric rather than measurable governance.

Two factors appear to be driving the government’s sudden urgency on the issue.

The first is the Assembly election, just months away, where minority sentiment could prove decisive in several closely contested constituencies.

The second is a petition pending before the Kerala High Court seeking the full release of the report, which is expected to come up for hearing shortly.

Church leaders say the sudden urgency amounts to damage control following the Left’s electoral setbacks in the recent local body polls.

Meanwhile, BJP State Vice-President Shaun George accused the government of selectively acting on minority commission reports, noting that the Paloli Muhammad Kutty report on Muslim minorities was implemented quickly, while the Koshy Commission report remains unpublished.

He also said RTI requests seeking the report drew vague replies, leaving petitioners with no option but to approach the High Court.

The Congress, meanwhile, has been accused by rivals of failing to press the government on the issue, despite its strong Christian support base in the state.

(Edited by Dese Gowda)